THE NEW STUDIO

NOTE: This section of the AFH UPDATE is a response to “The Function of the Studio,” an essay by Daniel Buren published in October in the Autumn 1979 issue (translation by Thomas Repensek); thank you to Liza Buzytsky for sending me the link.

In 1971, when French artist Daniel Buren penned “The Function of the Studio,” it was possible to describe a studio within the context of functions. This is no longer the case, in general. An artist studio, as such, is as fungible as the artist. The studio and artist have in culture been relegated to the bin of marginal applications. The artist is pro forma an avatar or persona, and the studio can be any node of contemporary translatable to both actual or analog and virtual or digital dimensions. The art for a studio artist is a thing, to the extent that a definition of practically any category of existence and/or experience may be superimposed upon it. Dividing and distributing the tasks associated with the studio is a creative operation that can be applied to any environment, system or body. The studio does not necessarily generate art. The artist does not necessarily need a studio to make art anymore. In fact, an artist is not required by society to produce art at all. The art of an artist is a state of being. To extend being is a qualification of art itself. Forty years after Buren’s argument appeared in October, the radicalization of art is to a massive degree completed. Those of us witnessing the contemporary phase of art, studio and artist, and the disruption and reformation of the construct Buren maps in “The Function of the Studio,” must recognize now that contemporary art can otherwise be defined as Extinction Art. Buren concludes that his art proceeds from extinction. It is a dubious claim, but one that resonates as a diagnosis in art analytics. Is art a sign of extinction? If so, what is then the new function of a studio and the artist who inhabits it?

The artist studio is more likely to be a content and media platform, than an “ivory tower.” The euphemism Buren adopts for his text is pretty much meaningless today. Connectivity to networks is a defining characteristic of 21st Century studio. A predominant feature of the common studio is selectivity in presentation and access. The curator role is integrated into the artist profile and production space. No border establishes distinctions among the habitat for creation and the means of communication. The artist and art appear on a spectrum of visibility. Projection is a skill in the artist mode, which is cleverly deployed to snare attention. Targeting the desired recipient of one’s programming comprises a substantial portion of “artist practice.” Designing and updating the features of all artistic components for optimum impact is vitalizing to the promotional flow. The integration of mundane qualities give the operational mix verifiable authenticity and currency. A key is driving the art machine, without seeming mechanical. The studio is adapting to the timeline, more than the deadline. With few exceptions, the era of blissing out in the atelier, smoking, chatting with collectors, lovers, poets, etc., engaging in the project of fabricating Real Art for the ages is extinct. Whether and for whom the romantic fantasy existed is a discourse unto itself. However, the simulation of that particular fantasy is a booming success, especially in the realm of social media. In this aspect, the studio has transmuted into the set, in which an artist character acts out the dream of being an artist, enabled by whatever economics and drive fuels such exertion.

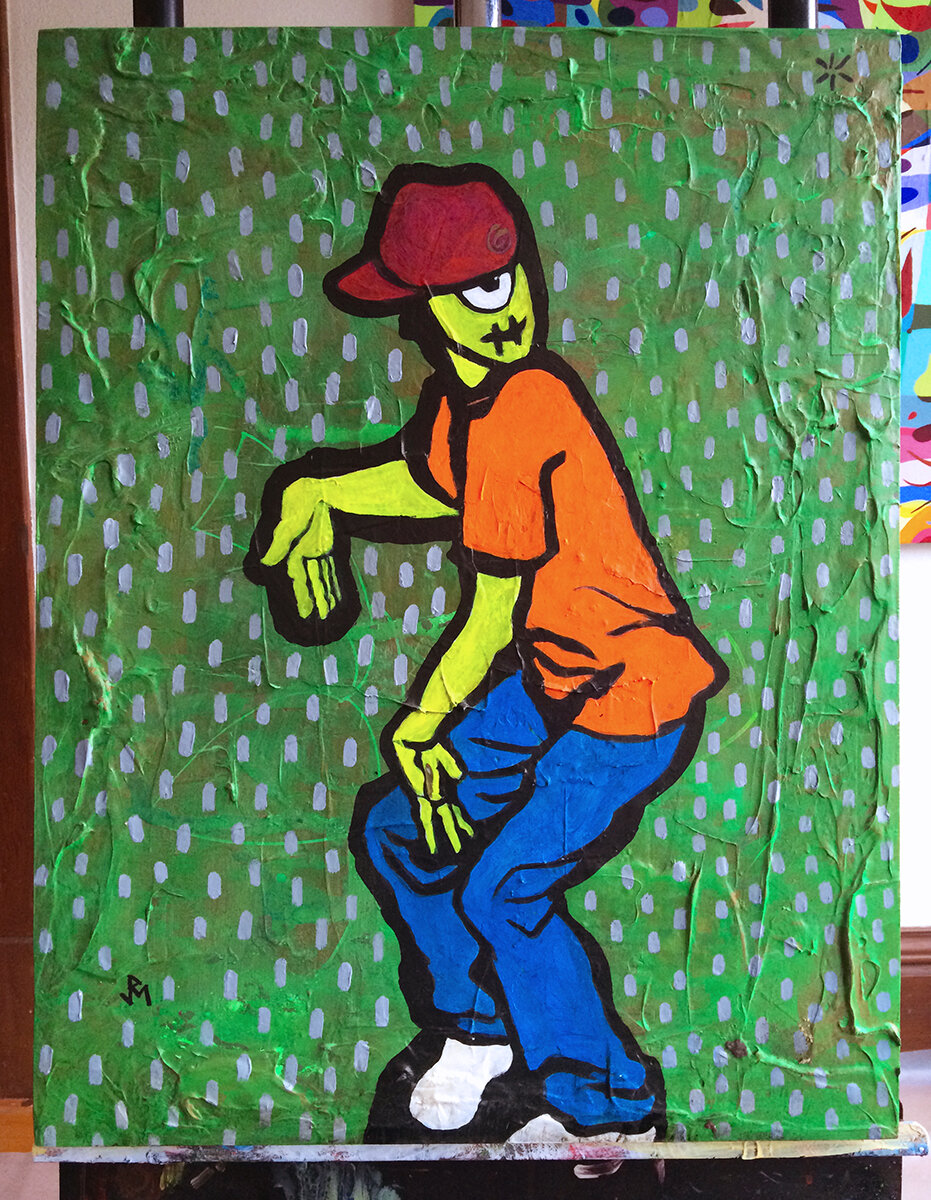

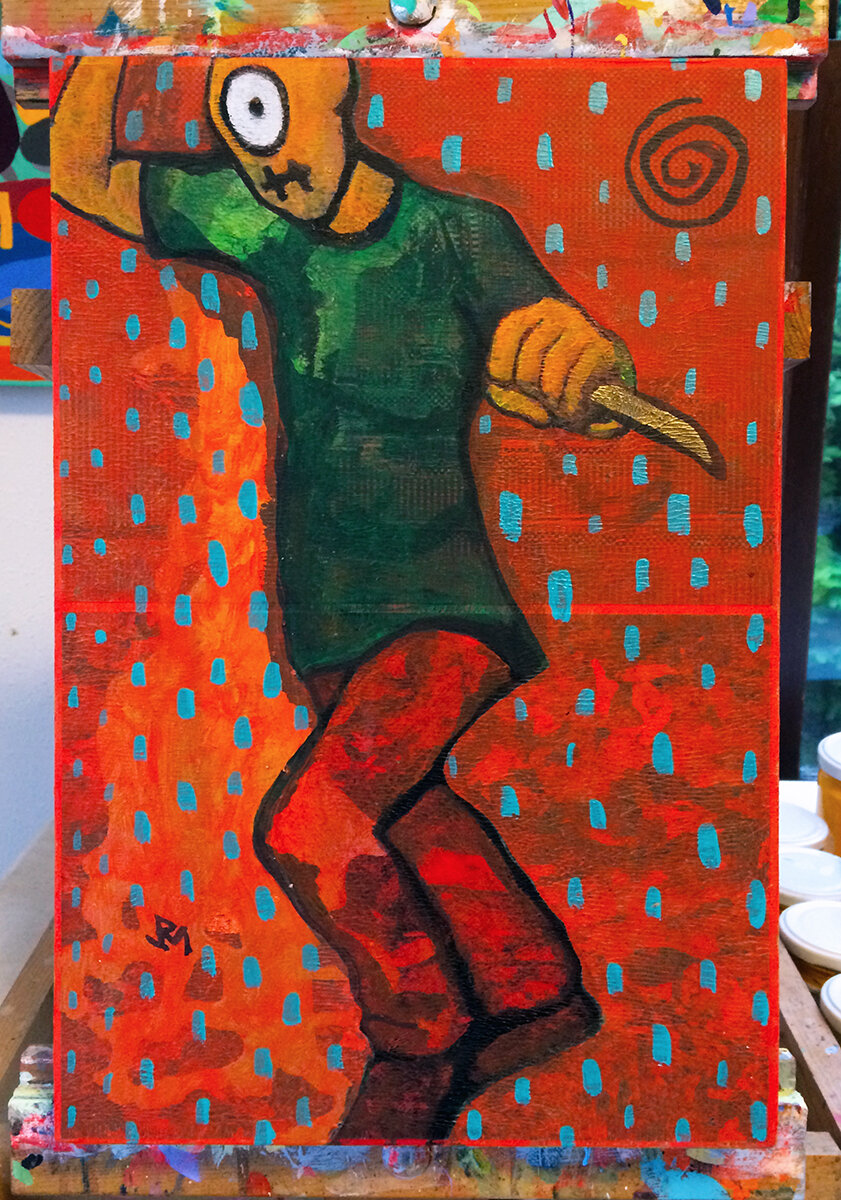

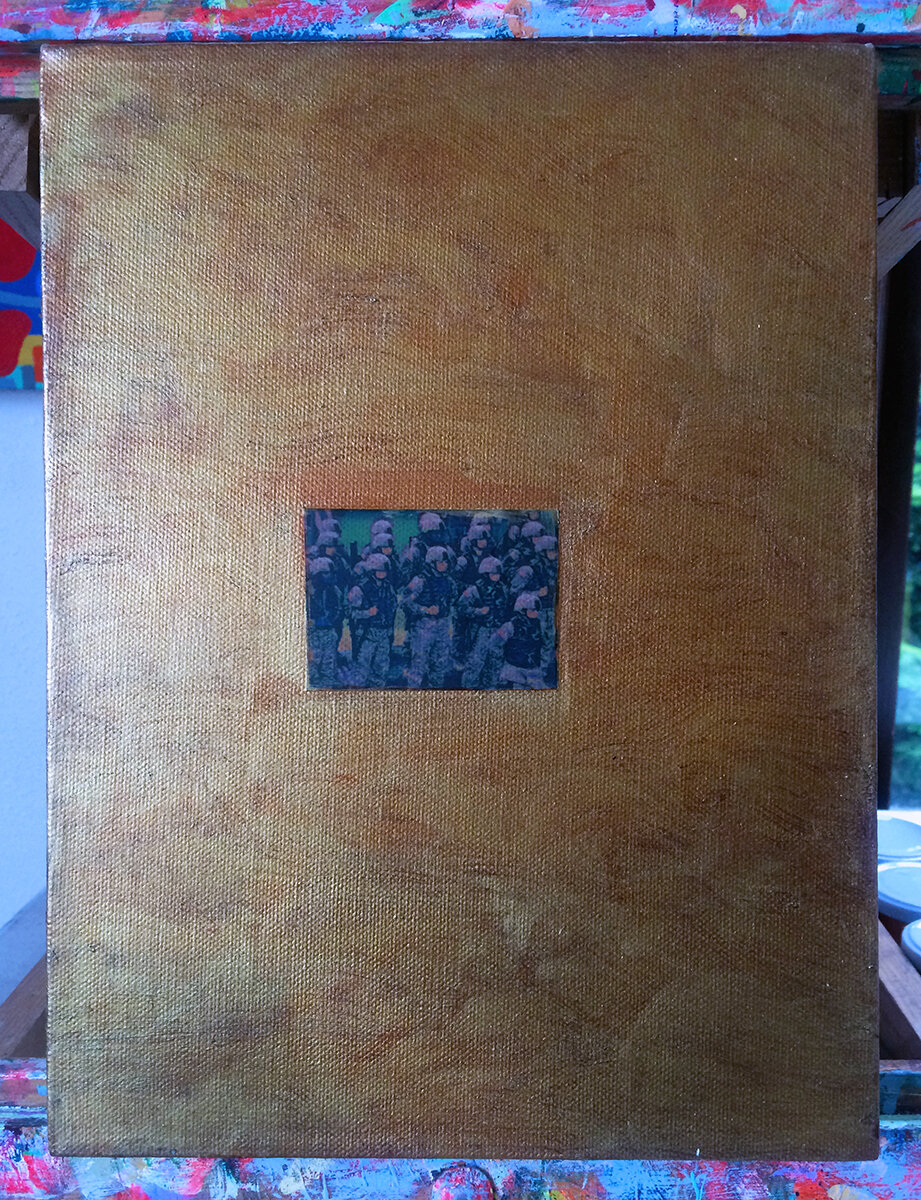

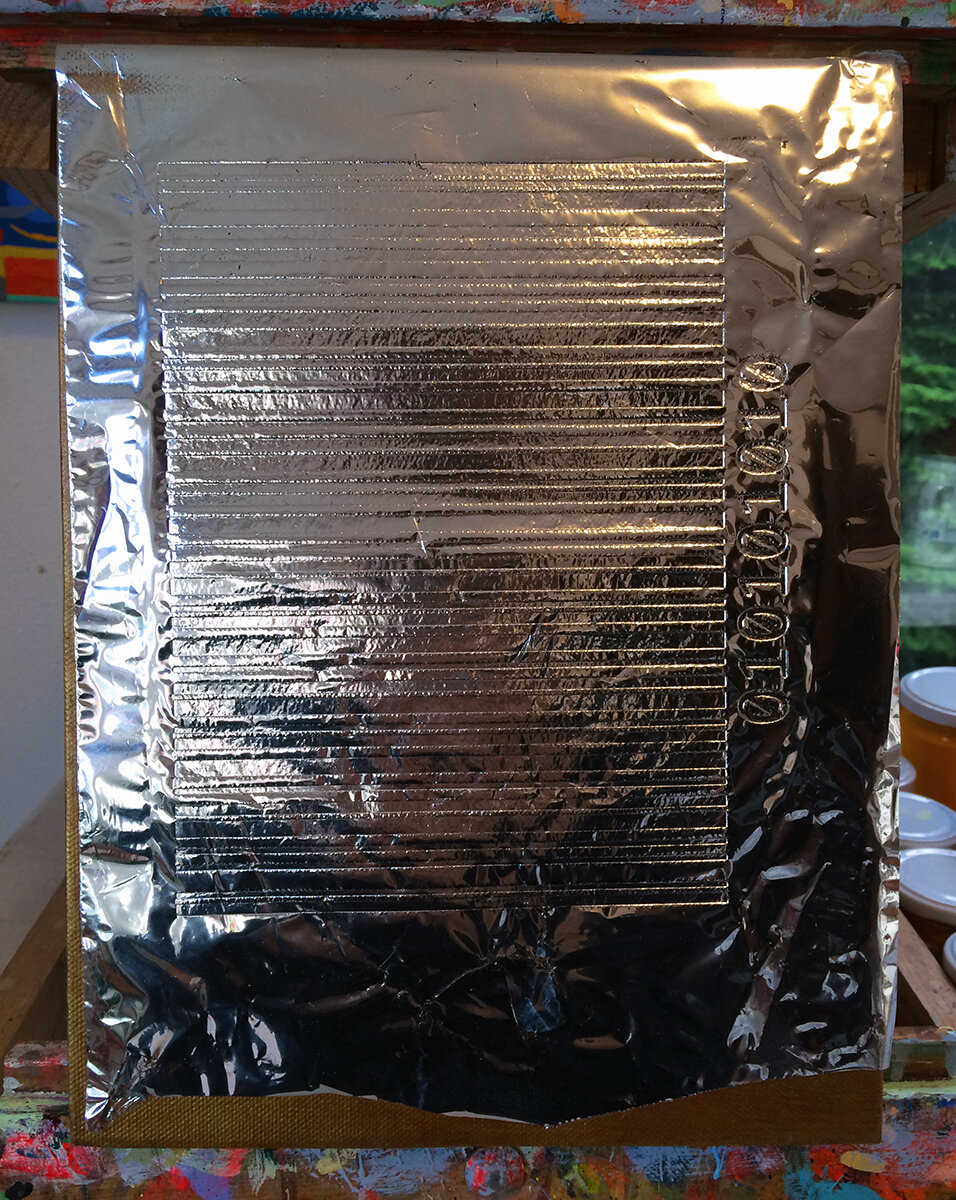

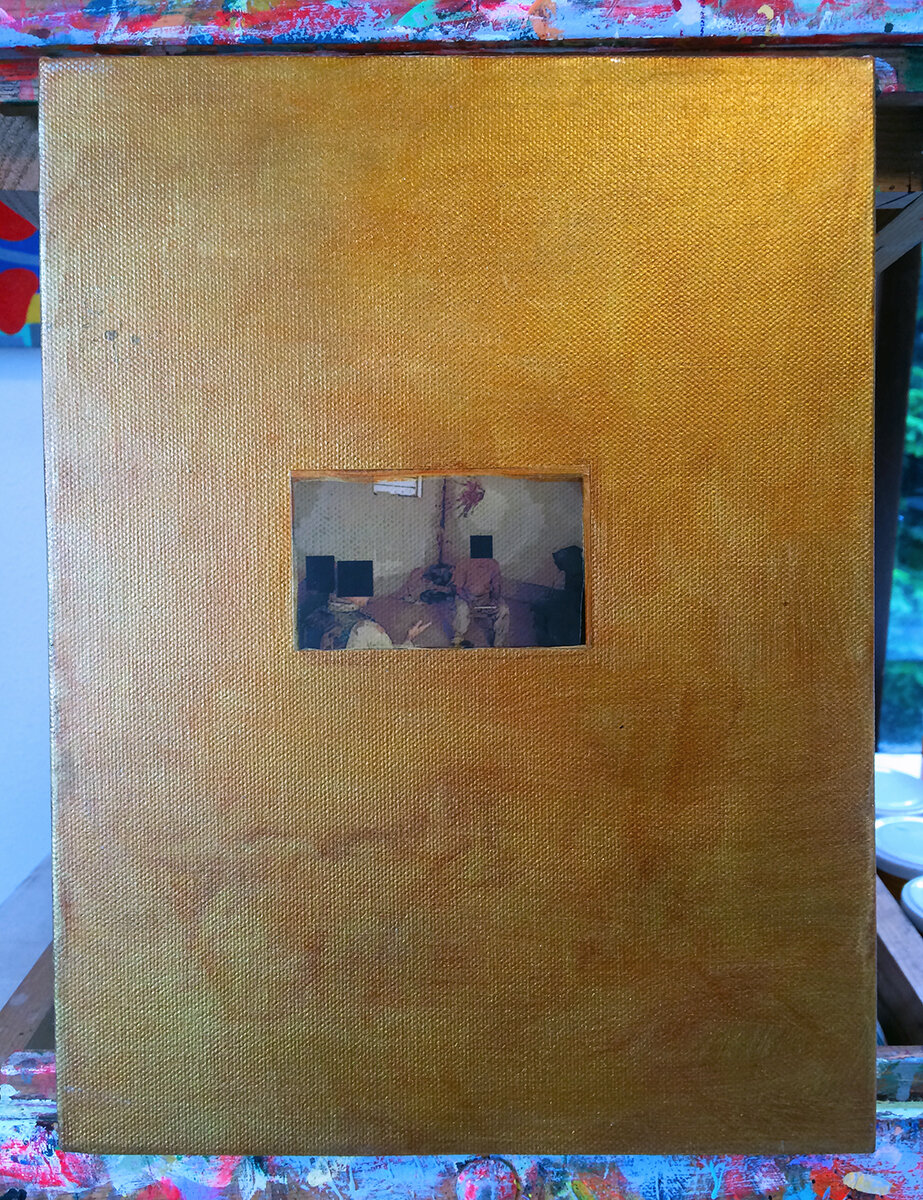

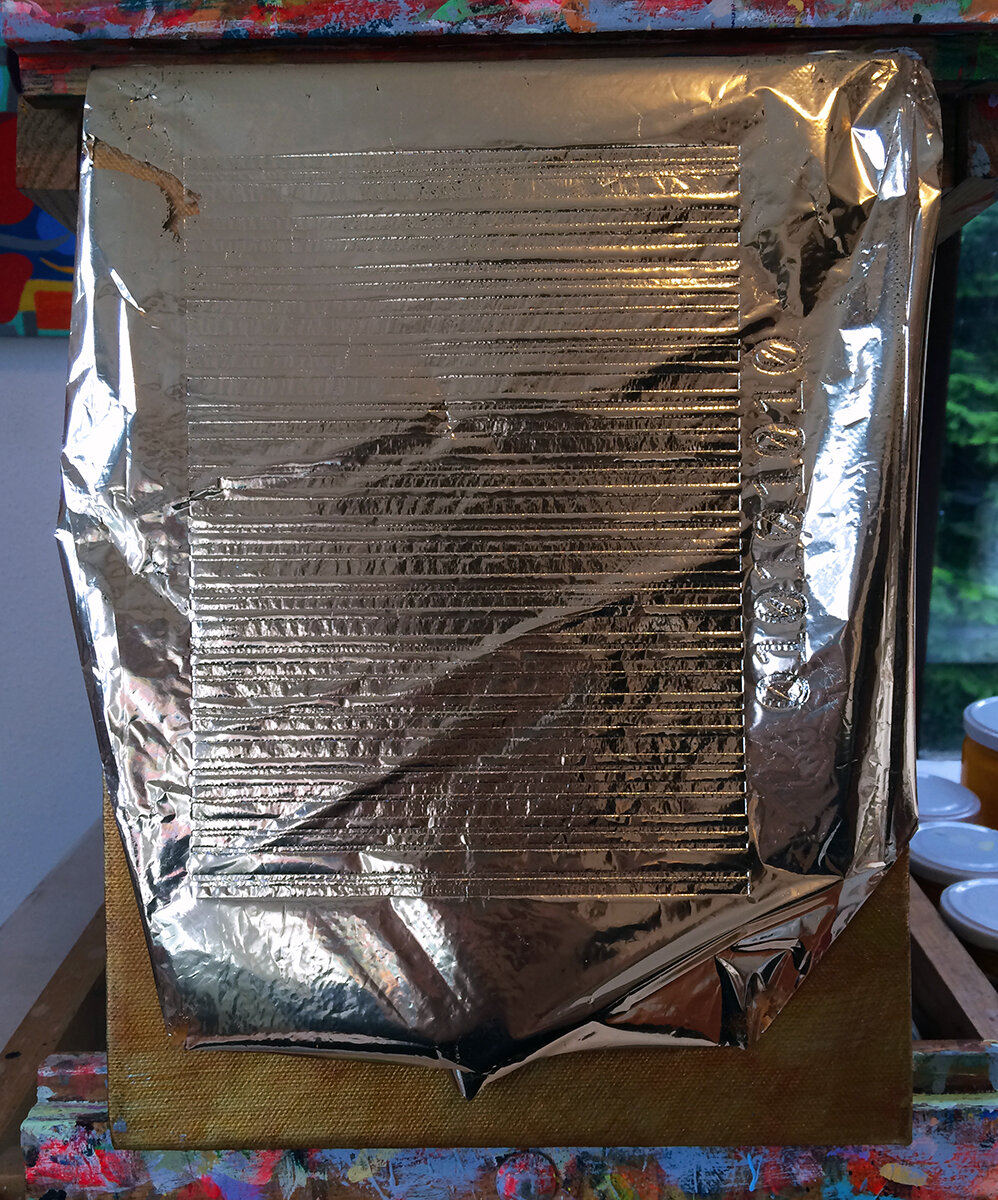

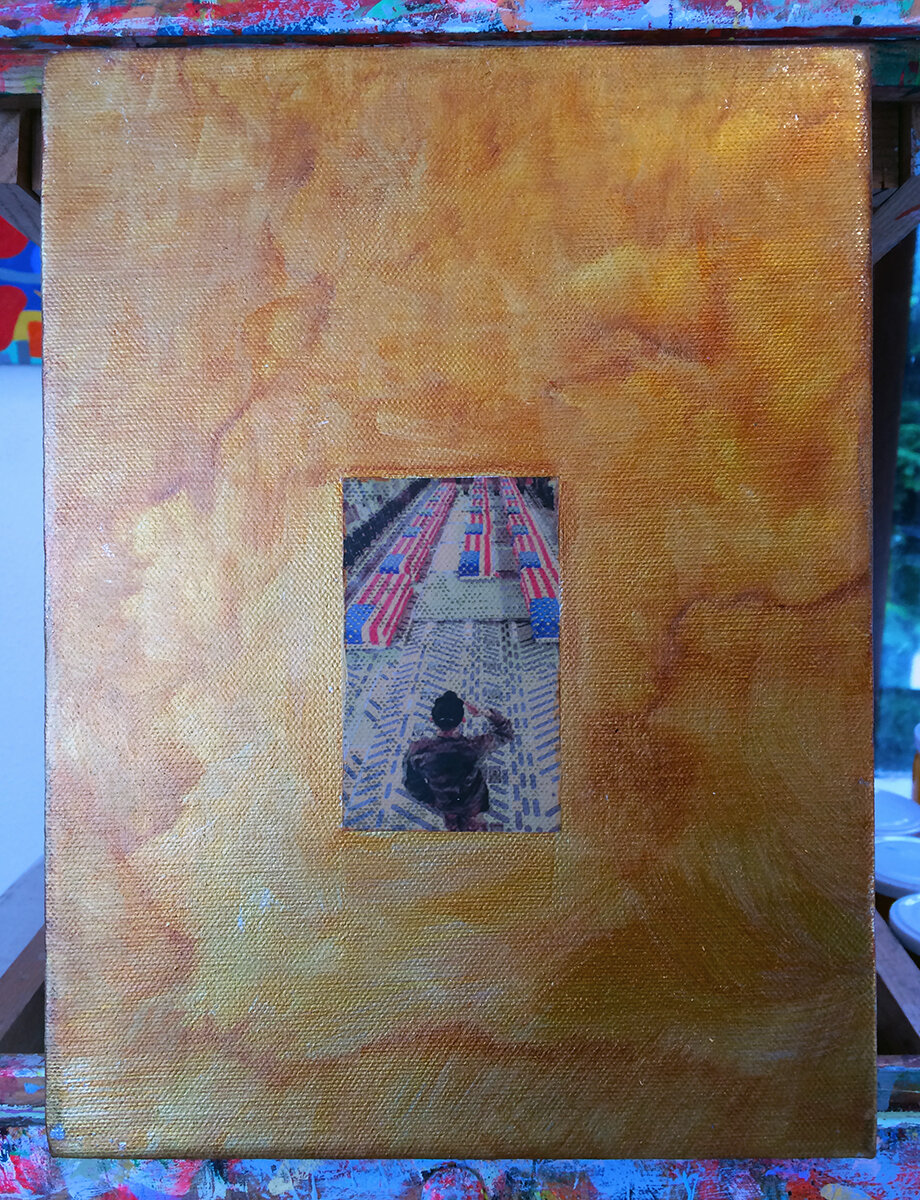

Currents, Flow and Reproduction Series #57

4D Quantities Series #12 [Meta-Elements (Array)]

Vinyl on Canvas

57" x 45"

$7250

Can anyone presently imagine distinct territories for the “world of the artist” and “the world of art,” as Buren frames the logistically bound domains transited by art as it passes through levels of viability. A problem in the conception of art beholden to architectures and institutional methodologies arises because the place for art is no more defined by the object and its subjective value. The competing regimes of property and price are complex, a hybrid configuration that increasingly provisions for time. The evaluation function of the world of art encompasses not only the art, but the artist and the artistic performance, all of which answer supposedly to a protocol, or at least some theory. The banana incident at the 2019 Basel Miami art fair is a case study. An argument can be made that the fair booth can be a temporary, interactive art studio, based on a confusion of conventional aesthetics. In the media circus attaching to and enveloping the banana-as-event, art itself is pushed toward extinction. This absurd PR dream, complete with potent viral meme effects, is not an anomaly in the matrix of artist worlds. It is not a bug. It is a novel version, an update, for the Medium of art, as such. However, the privy media scanner or analyst knows to follow the story beyond the bright lights of publicity. The scenario unfolds in the spirit of frivolity, but eventually arrives at the dark door of scandal. “EPSTIEN (sic) DIDN’T KILL HIMSELF”… So reads the second vandal inscription for the now-famous installation. One can summon all due respect to a weathered, decades-old idea for a “world of art,” and yet be surprised that a practitioner of institutional critique (another antiquated narrative modality) has not attempted to visualize the network that connects Jeffrey Epstein to central figures and entities populating our Big-A Art World. The shifting parameters of meaning associated with the performance of art throughout the scheme for art suggests that, at times, the world of art itself is engaged in the project of making itself art. Then, would the studio be the world, for the artist, and who, exactly, could properly identify as an artist in that milieu? The urge for everyone to be an artist might finally therefore be sensible.

While one can appreciate Buren’s sketch of the studio archetype, and appreciate even more his notes on the rendering, the reductive perspective of American art and artist in “The Function of the Studio” requires remodeling. In New York, and to a lesser degree in cities across the United States, the artist and the artist studio are as much creativity indicators as anything else. The association of gentrification with an amorphous notion (see R. Florida) about artistic or broadly categorized creative activity is expressed in a burgeoning business for studio-factories, divided into marketable units, typically located in formerly challenged or precarious neighborhoods and districts. The trend coincides with America’s conversion (where possible) from productive manufacture and diverse retail exchanges magnetized to national, regional, city, town and village centers, to a mishmash of creative class services and big box monopolies dispersed according to developmental urban plans and sprawl. The massive dislocation of people, especially after the Great Recession, due to foreclosures and the accelerated redistribution of wealth from bottom-to-top economic cohorts, has intensified many effects visible in the configuration of our residential and commercial property markets. Analysis of the impact on artists is mostly anecdotal, although some arts commissions and non-profits have attempted to accumulate metrics for policy purposes. Advocacy for sufficient and affordable art studio supply to meet need, if not demand, has led to the establishment of programs and projects for setting aside analog space for art production. One big problem with this approach is the prevalent de-definition of art. The struggle to provide the spatial means of art production is complicated in a society in which the question of art identity remains unsettled to the degree it is. Exacerbating confusion over nominal or definitive art, we face a severe lack of clarity for studio construction and composition. There are no substantive, much less universal, guidelines or regulations available to impinge on the power of real estate owners to call whatever building a studio complex, or list whichever room in a building as a studio. In America at least, what constitutes “the artist studio” is dictated more by the broker than the artist. Exceptions exist: Well-funded artists can design their own art space; studios are still integrated into academies; and in many varieties, compounds or edifices facilitate art creation under management of artist collectives. The collective approach varies. Sometimes the origin story for these projects arises from the era when Buren wrote his essay, when artists in the communal spirit of the day pooled resources and acquired often-destitute or undesirable structures and with colorful industriousness erected their own alternative art co-labs. In other cases, a patron or art scene-minded entrepreneur or trust funded artist invested in real estate and set themselves up as benevolent dictators to the artists who would rent space from them. Squatting is tolerated less here in the States than elsewhere, but there are some famous (and notorious) instances of space appropriation by diverse groups of artist-identifying individuals. The most radical and compelling phenomenon in the period (1971 or -9 and 2019), in terms of confronting the issue of spatial art production technically and theoretically, occurred during Occupy Wall Street, or as direct result of the movement’s dimensional actions in the field of arts and culture. That story has been largely obliterated, and will not be redressed in this essay. To comprehend the mechanics of artful OWS, and the suppression applied to the Occupy movement from 2011 through the present requires a thorough treatment, the main points of which are available elsewhere in the AFH platform. At the moment, one only has to study Occupy Colby/The River Rail to get the measure of extensive co-optation of occupational programming perpetrated in the world of art. The subsumption of OWS-situated advances into the status quo mirrors a dynamic pervasive throughout layers of human enterprise comprising what we imagine to be an integrated, progressive, modern civilization. That enlightened imaginary has devolved into something much darker.

AFH Studio Nashville, ca. 2001

Buren does not focus on a historical studio, instead choosing to accentuate the systematic. The etymology of the word studio offers an obvious thread to unravel. The studio is primarily a space in which study happens. To ignore the implications for the disposition of the artist in the room thus dedicated is to erase the impetus of the combine. What is the curriculum for art study? How does the contemporary studio support the objectives instilled in the designated architecture. The frivolous occupation of an art studio by whomever in no way assures aesthetic merit. Artistic skill or substance is not transmitted to an individual by osmosis. Aesthetic expertise is not an invested quality derived simply through proximity to the type of architecture delineated in Buren’s or any other serious survey. The function of the studio is less important than the art function that it enables. Missing in Buren’s essay is a relevant depiction of a vertical order for the art studio interior. Given the usual cubic vernacular of buildings in the West, the apt metaphor for the shape of spatially defined production is directional. If our orientation is decoupled from the hierarchies of Church and King, then the studio becomes a site for secular progression, digression, regression, procession and so on. The nature of studio work is serial, sequential. To attach the natural, secular studio to history is a serious matter. To do anything else is only diversion, in a manifold sense. A studio is hence no place for escapist entertainment and the fictional narrative. Yet so much of the studio production promoted as such today verifies a fallacious appropriation of the studio, starting with its basic meaning. To characterize the process by which the art studio has been emptied of its inherent quality as neo-colonial, a base, banal extraction and exploitation venture, is not to be hyperbolic. An evolutionary analysis of the art studio yields intelligence on the consumptive aspects of a world order that insists art and artist be consigned to functional non-utility. For the world of art assesses the functionality of the product art within strict confines, narrow parameters, while cynically celebrating the liberation of art from any aesthetic ground or bearing.

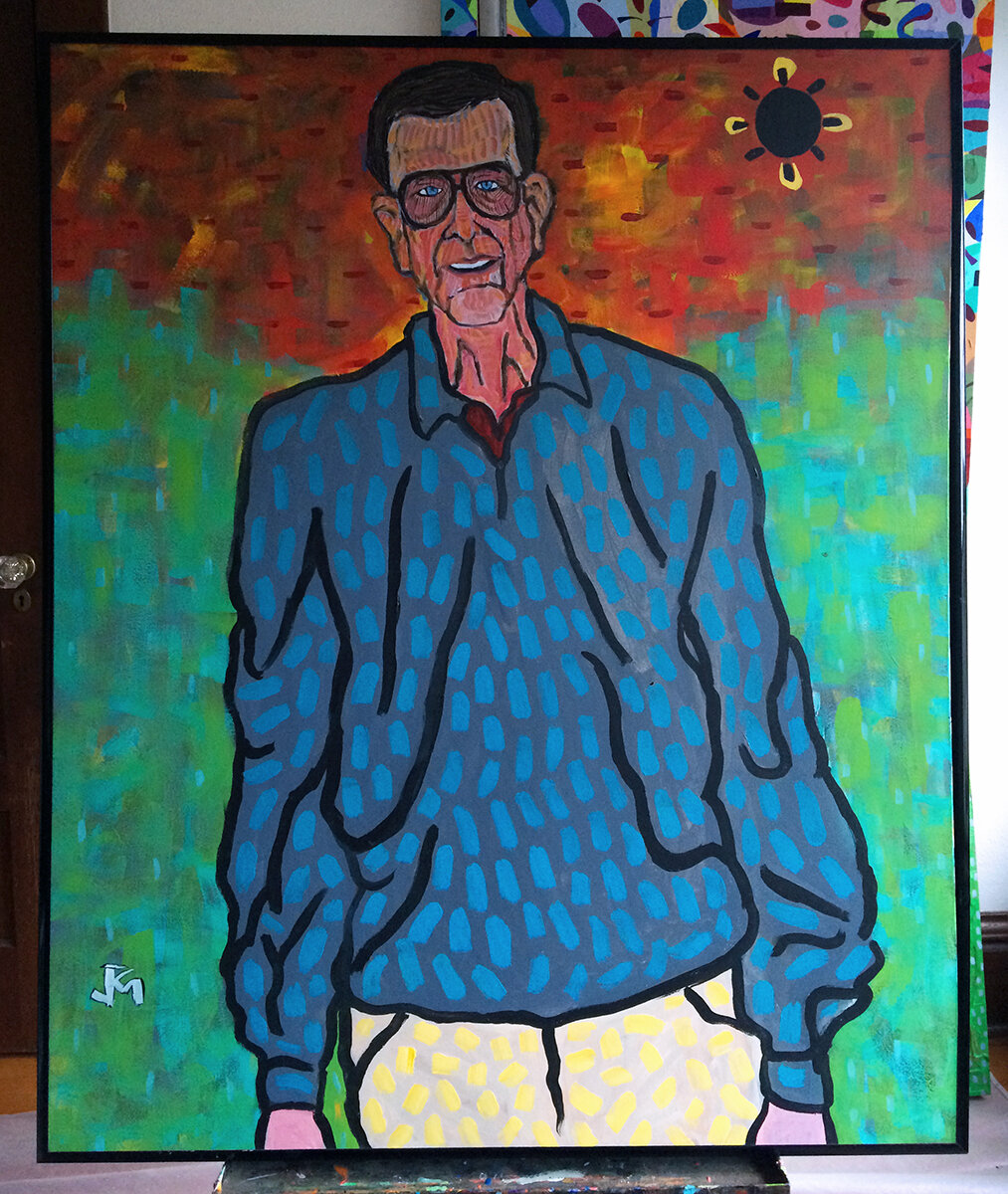

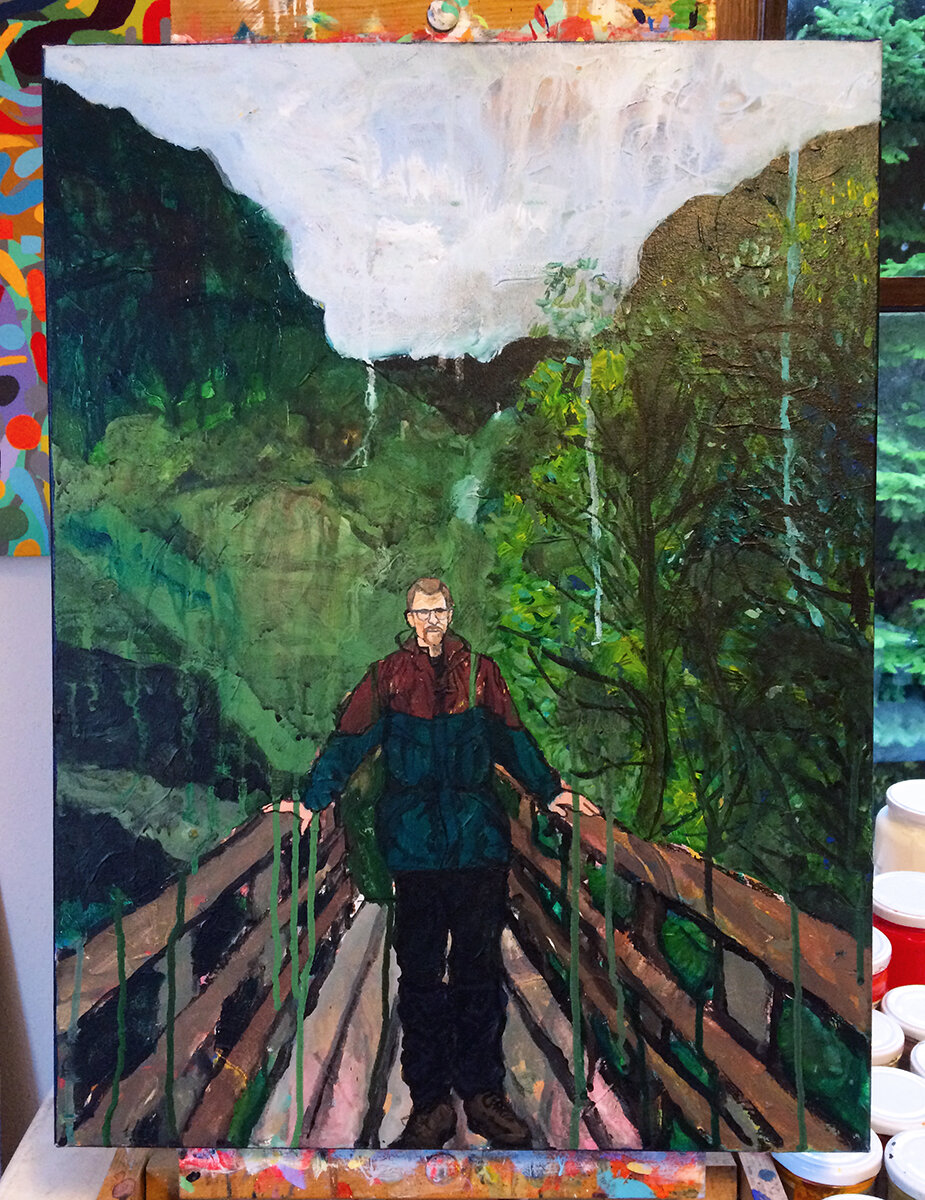

Morris Graves Foundation (ca. 2004, photo by PJM)

One cannot address the actuality of the art studio in the contemporary aesthetic imagination without consideration of the art residency phenomenon. It might be that artist residencies have usurped the subtext of art production altogether. The resident artist is situational, and art product within a residency environment is routinely diminished or explicitly made optional, which is tantamount to formalized managerial ejection of artistic objective intent. Some artists have given over to residential nomadic lifestyles. The curriculum vitae of the serious artist is considered incomplete without exotic or prestigious residencies. The residency proposes episodic art, and that the artist be as mobile as the art produced. Many residencies charge the artist occupational and service fees, which confuses the exchange. Is it a rental, therapy or an award? The network aspects of artist studio residencies adds to the ambiguities. Artists may be expected to perform a range of services as part of their residential package. These can include teaching commitments, community service, informal social interaction and so on. The documentation of artistic activity in the residency context can veer toward surveillance. The relationship between residential host and any art produced during the artist occupation of the resident studio can be contractual, branded and prolonged. Again the apparatus within which the artist is expected to perform art production encourages the divestiture of the thing from the maker of the thing, which is not the same as art’s transition from one metaphysical frame to another. The conception of art is relentlessly interrogated by the precepts of possession. Over time, the lineage of art’s value is subjected to provenance. Today the layers of ownership extend endlessly, minus the artist, who, after relinquishing the art, is, in most of the world of art, deprived of any claim to the art’s compensatory value. Art reproduction, its virtualization, has only made matters worse.

AFHstudioBK, 2010

Buren turns away from a condition of art life that has become ubiquitous. He writes parenthetically, “We will not discuss those artists who transform part of their studios into exhibition spaces, nor those curators who conceive of the museum as a permanent studio.” The scene he dismisses has emerged and assumed prominence, since “The Function of the Studio” was published. The blurring of boundaries within the triad of studio-gallery-museum provides advantage to art world players who “wear many hats.” The shift in art industrial practice and organization is causal, due to economic pragmatism. Most of the employees of art enterprise do not earn sufficient living wage from any single job, and the best of those jobs are found in expensive places. Instead of organizing for improvement in remuneration, most art professionals instead chose to improve their circumstances by diversifying their resumes laterally. It is not uncommon for art pro X to identify as a hybrid, introduced as artist, researcher, teacher, writer, curator, etc. The pressure to accept normalization of de-specialization within the labor framework for the arts intensified with the gutting of Humanities-based institutions of every description over the past two decades. The post-2007-Crash realities ensured that survival in the arts ecosystem would be Darwinian. At the top of the arts economic, after the initial shock dissipated, it was obvious that the prime beneficiaries of the catastrophe remained invested in the most exclusive, rigged portions of the art exchange. The repercussions continue to affect the topology of art through the present. Simultaneously, the emergence of the Asian (really, Chinese) art market, designed overtly to compete with the West’s, would undermine a centralized narrative for art in the 21st Century. The primacy of the global art fair network drastically reformed the logic and order of the art business. Regional markets (e.g., Dubai) could be artificially erected with amazing speed. The new millennium commenced with an unprecedented redistribution of power and money. The collector mobilized, and with unimaginable wealth, has driven the formulation of a world of art that bears little resemblance to the one in Buren’s text. Vanity art museums, (e.g., the Broad and the Walton’s Crystal Bridges Museum) are again a thing, echoing the heyday of the early robber barons, like Frick. The accumulators and heirs of great fortunes across the globe can again divert some portion of their spectacular resources into quasi-philanthropic ventures. Some, like Moishe Mana, have identified opportunity in cultivating artists, throwing relatively enormous funding into exhibition projects, art studio and storage facilities, and strategic arts and cultural development. The public art sector is through policy deprived of the means to compete. The wholesale privatization of the world of art mirrors the trend determining society and its relations. All humanity is living on a planet “run more like a business.” The consequences are clear, and art is hardly immune. With business in charge, every thing, including the studio/artist/art/gallery/museum, etc. is only a function of price. Protocols within the systemic architecture are subject to the whims of the funder and management minions whose allegiance to that bottom line dictates something like security. Integrity and ethics have given way to allegiance and obeisance. The art press and critics have been purchased and culled. The destruction of academic tenure assures that opposition is a non-threat to power. Perhaps it is now impossible not to consider the artist on a spectrum of complicity. What originates in the studio are signs of complicity by degree, which explains the discursive difficulty posed by today’s originality. The superficial complaints pushed under the auspices of industrial criticism (e.g., Zombie Formalism) into the new mainstream for popular aesthetics, belie a devious, endemic corruption. Whether immoral or amoral, nothing about such critiques or their affinities is rational and authentic. The civilization run like a business will get the art it deserves.

AFHstudioCGU, ca 2007

Art’s absurd, abject, alienating function envisions expectation of wish fulfillment. Art has other, more valuable functions. Art registers immediacy absent name and number. The artist can study this facet of art and enjoy continual inspiration and reward in the studio. Non-artist observers fortunate to tour or congregate in a dedicated space for art of this species will experience wonder. The art such a studio propels into the world will contain the wonder, and if enabled, will spread that sensation wherever it is installed. The grievous act of removing wondrous art from universal public circulation is not justifiable. The failure of society to circumvent the outlandish, selfish demands of megalomaniacs is evidenced in art prisons (e.g., the egregiously titled Geneva Freeport). Hoarding of treasure is a feature of tyranny. The practice is antithetical to democratic principles. The point is, democracy and property are not compatible where people and things intersect, especially when the thing in question is an expression of humanity itself, as art is. The same is true for food, medicine, shelter, love and other existential necessities. Desire and seduction cohere to wish fulfillment. Thinking of art as discipline defines the function of the art studio as a hedge against the destructive urgency inherent in man and therefore art. So the studio is a funny, sublime, welcoming room. The lighting scheme should be sophisticated, because art now is both reflective and emanant. The artist should study natural light and darkness and their cyclic flow, as well as electrified technology, including luminescence. Artificial light has transformed human experience over time, and proper art will acknowledge that reality. On technology and art, much must be advanced, particularly with regard art studio processes. Buren notes the deployment of artists in studio buildings (sculptors at ground level, painters above), and the practicality of that vertical distribution is contingent on gravity, volumetric mass, transport logistics, etc. The contingency of art/artist/studio on electrified technology has necessitated a near-absolute reassessment of the artistic enterprise, as is true of humanity itself.

AFH Flickr, ca. 2007

![Currents, Flow and Reproduction Series #57 4D Quantities Series #12 [Meta-Elements (Array)] Vinyl on Canvas 57" x 45" $7250](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/501abbd4c4aaab20160f16af/1576784754725-VN0KGUPQAHDKH5H67LLT/cfr57.jpg)