POSITHETICA: The Final Art for Humans MEGAzine

By Paul McLean

Revolted by the butchery of the 1914 World War, we in Zurich devoted ourselves to the arts. While guns rumbled in the distance, we sang, painted, made collages and wrote poems with all our might. We were seeking an art based on fundamentals, to cure the madness of the age, and find a new order of things that would restore the balance between heaven and hell. We had a dim premonition that power-mad gangsters would one day use art itself as a way of deadening men’s minds. — Jean (Hans) Arp, Dadaland

“POSITHETICA” is dedicated to the Giants who strode mightily into the Lost Horizons.

With great sadness, for Sylvere Lotringer, Semiotext(e) founder, in commemoration of his passing on November 8, 2021:

We live in a world in which everything is constantly evolving and revolving, everything circulating through networks which instantly communicate with myriads of other networks. So it is very important to understand how the entire system works, and how it represents itself. Outwardly it appears as a decentralized system, a global rhizome moving with near speed of light, a complex semiosphere without inside or outside, which keeps reversing itself seamlessly. This system is all the more imperceptible that it circulates everywhere. It blocks the horizon, and we don’t have enough distance to identify it for what it is. And yet, looking at it from closer up, we may perceive the main structures of this dizzying technological maze. It is powered by banks and international corporations that operate with near autonomy, according to some quasi-automatic strategies. So the image of the rhizome appears overall adequate, but the intricate systems of command are still prevalent and it just takes something unexpected-a financial crash, terrorist attack-to reveal the way they operate and what they really are about. — Sylvere Lotringer, interviewed in 2015 by Jason Hoelscher for ArtPulse Magazine

David Graeber, September 2, 2020:

And of course one could write very long books about the atrocities throughout history carried out by cynics and other pessimists...

In egalitarian societies, which tend to place an enormous emphasis on creating and maintaining communal consensus, this often appears to spark a kind of equally elaborate reaction formation, a spectral nightworld inhabited by monsters, witches or other creatures of horror. And it’s the most peaceful societies which are also the most haunted, in their imaginative constructions of the cosmos, by constant specters of perennial war. The invisible worlds surrounding them are literally battlegrounds. It’s as if the endless labor of achieving consensus masks a constant inner violence — or, it might perhaps be better to say, is in fact the process by which that inner violence is measured and contained—and it is precisely this, and the resulting tangle of moral contradiction, which is the prime font of social creativity. — (p. 11, 25-6, David Graeber, “Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology,” 2004)

Occupy Wall Street, September 26, 2011 (Photo: PJM)

In loving memory of Jean-Luc Nancy

Art is the presentation of presentation insofar as presentation - the eternally intact touch of being - cannot be sacrificed. - (p. 138, The Sense of the World, “Art, a Fragment,” 1993/trans. 1997)

“The End of the West,” continuous outdoor exhibit process, Astoria, OR

It was, in fact, nothing more dangerous than a democratic forum of free opinion that in its protean liveliness and free-form contingency could only expand, did expand, in fact, and persists today in all our quotidian discussions of popular art in this nation. In the world of high art, however, a bunch of tight-assed, puritanical haut bourgeois intellectuals simply legislated customized art out of existence, in a fury of self-important resentment. Because Hollywood trash like Harley Earl and lowriders like Luis Jimenez became conversant with the economics of their beautiful, powerful game. — (p. 72, “The Birth of the Big Beautiful Art Market,” Air Guitar, 1997)

A THING & ITS SELF

“Ghost Dance Shirt” by James Havard (1977), PAFA collection [“America’s first school and museum of fine arts”]

A NOTE FROM AN AUTHOR

1

(In the awkward manner of the stand-up comedian, performing in a near-empty theatre.)

bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk*

…I met James Havard at Elaine Horwitch in the late 80s. James had several shows with Elaine. I worked there as an installer and shipper-packer. It was my first real art job, and it was fantastic, although my personal life was a train wreck at that time. I have so many stories. Like most of Elaine’s Southwest contemporary artists, Havard was a character. He spoke elegantly, with a charming Galveston twang. He was fun, funny and gregarious. One time, James invited us to have dinner at his beautiful new Santa Fe house with Tom Palmore, another terrific artist showing at EHG. Tom had just been released from prison and was a bit shell-shocked. James prepared a marvelous meal. I think Tom helped, but the details are foggy, because of the wine. It was French, top class, but I drank way too much, and by evening the gathering got chaotic and bad. It was my fault, and I never had a chance to make amends. In the course of preparing for “Occupy 2021,” I found out that James died in December 2020, a year ago, almost to the day. I learned that he had been disabled by a brain hemorrhage in 2006. After that, he moved back East to Pennsylvania to be closer to family. James was born in TX, and studied at PAFA, in Philly. I loved the big abstract illusionist paintings that put him on the map. He would squeeze juicy threads of oil paint from the tube directly onto the surface, and it would interplay with a sprayed shadow underneath. Really 4D. James sold like crazy, and he became an international artist. But the little paintings he made after the hemorrhage, after he lost use of his legs, they are really tremendous. They have an art brut quality, which is consistent with all his art. Gone, though, is the auto-shop finish, the surface fetish. The small late works are playful, and exude insistent joy, celebrating life and love. James was an American artist to his bones, and Texan through and through, but he had a Parisian, romantic heart. He worked best he could to the end, and he was a Master all the way through to the denouement, an inspiration. This section is dedicated to you, James…

*James Joyce, Finnegan’s Wake

I never really thought about why I was painting or what the paintings were. They just happened. I start working. It comes out. I don’t philosophize on it a lot. I leave that up to the critics. (Laughs, sips wine.) — James Havard, 2019

coil

∞

There was a technical error saving the first draft of the first paragraph of the Introduction, causing it to disappear, gone forever. Gate gate para gate para sam gate bodhi swaha (Sanskrit: गते गते पार गते पार संगते बोधि स्वाहा). Such is the brutal, fragile nature of online, computer-based, artistic production, signified in a spinning beach ball icon, or any of a bajillion animated variations: bars, dots, clocks, sprockets, hourglasses, and so on. The computer says to the user, “I am processing… This may take forever, never being completed. Let us wait together. I will show you a symbol, an animated icon, on which you can meditate, a clever or faux-empathetic signal that expresses my utter lack of emotion, because I am a processing machine, both inert and busy. You are human, relying on my work, waiting for the result you want or need. ‘Please, be patient.’ We understand, my Encoder-maker(s) and I. Humans do not find waiting for a machine to finish a task pleasurable. My EncoderM(s)[EMs] are human also and installed this graphic to communicate “processing” to you, the user…”

MEGA Dim Time, Spiral + Ladder, Signature and Signal (2021)

elementary

∞

The Net gods can be cruel, but the severity of data loss is relative, scalar. Losing an opening paragraph in a text is not the worst kind, even if I lost an hour of creative labor. Even if the lost paragraph were the greatest ever composed, and the glitch that disappeared my paragraph is not supposed to happen in my Content Management System, one I have been using, paying for, for years. To put the loss in perspective: ships laden with treasure did not sink to the bottom of the ocean; cities did not die in flood, eruption or other conflagration; it was no mass casualty event, caused by a bomb, prehistoric monster or asteroid from space slamming into the planet. The Great Library of Alexandria did not burn - again. My little data loss was not even close to the worst I’ve experienced, my tale of woe for which is too painful for me to repeat here. Computer-based systems are exceedingly fragile, and a Crash is going to happen, eventually. The breakage can be connective, interrupting the flow of electricity that energizes every component not battery-powered. Hardware blows out; or the result of “wear and tear” or bad manufacture; or because your device is dropped, or damaged by liquids, heat/fire… Software freezes, due to corruption of the files, bad design and engineering, viruses and malware are another threat… In short, fragility is characteristic of our digital existence. We adapt. We discover workarounds. We save data to back-ups. We add secondary networked systems. We move what we can to the Cloud. We de-centralize, we archive, we update, we invest in surge protectors. And we discover over time that no computer-based network can be completely safe, fully protected. Any system can be cracked, hacked, whacked by something or someone. Proof: log4j…

MAMCO, Geneva, Switzerland (side entrance) 2010

It wasn’t my fault, and I don’t want to blame myself (too much). After all, I was doing the right thing by saving the content, by backing it up, if only in the Cloud, on some server in a databank to which I have no direct access, except through the provisional, unidirectional interface. I myself have found it troublesome to compose creative texts in the digital media and archive the material simultaneously IRL (In Real Time). Generally, I am a fan of auto-save features in text creation and imaging software, except when those features malfunction. And so, at a little after 9AM, Astoria, Oregon Time (PST), it was better for everyone to be someplace other than near my workstation. At a safe distance, you wouldn’t have heard the howl of despair, the shouted curses. My tantrum wasn’t as bad as those depicted in early web viral videos, showing geeks losing it and smashing up their gear and cubicles. Remember, LoL? That’s not me. I have coping tools. I know the drill, by now. Get up from the computer. Breathe. Walk away. Come back later, when you’ve cooled down. Do nothing to make the situation worse.

And it is not simply a problem of unstable hardware and degrading data. The seemingly unremitting digital revolution we are embarked on means that most digital technologies are outdated every few years and replaced by newer versions. Technologies that were ubiquitous barely a decade ago, like floppy disks, now look like archaeological relics. It takes only a few years, if not months, before software environments are replaced by newer versions, often with limited backward compatibility. It is possible to say, without fear of exaggeration, that no other period of human history has experienced the same rate of technological obsolescence than the digital age.

Crucially, this cycle of obsolescence is not simply the result of the inherent instability of hardware or the “natural” result of the relentless process of techno-logical innovation. We also live in the age of manufactured fragility. — “The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Fragility” (Rubio and Wharton, 2020)

…As far as I can tell, most computer users at some point lose something they were working on, because of: a software glitch; power outage or interruption; fried, broken or stolen hardware; and so on. One of my earliest entries in the first AFH blog (Thursday, August 22, 2002), I posted, “My ethernet card got fried by lightning last week, so, as you saw below... Paul was a sad bird & fell way behind on his AFH work.” I still experience cellular flinch and recoil when I think of that episode, which entailed no data loss to speak of, but did cause a cold turkey separation from the Internet on the home PC. Tech lock-out is another Beast altogether, a matter of temporary or permanent lost access to digital worlds you previously inhabited and want to again ASAP. …Not equivalent to data loss or gear breakdowns, although terrors can come in a horrific bundle, a different flavor of miserable angst. Data loss is special. The moment you realize the data, your investment of labor and attention, in virtual currency, is unrecoverable - the heartbreak, anger, shock, grief, bitterness, despair - can be devastating, overwhelming; presuming you care about your content, or your livelihood is dependent on the lost data, or you could not spare the time devoted to the lost task, and you are psychically impaled by the knowledge that whatever you do to replace the file, disc, device or computer, the next iteration will not be exactly that thing that has disappeared, permanently. But Who knows, says the optimist, maybe this version, a subsequent replacement, will be better! An improvement!

“Sad Bird” by John Guider (Circa 2001)

Then the contrary inner sentimentalist interjects: No, you fool! Done once, done always! Recall Heraclitus, the man and the river! potamois tois autois… I think any perfectionist can empathize, but the feeling of attachment to conception of all varieties is really an artistic one, and in a sense belongs nowhere close to a computer. In the digital realm, uniqueness is recursive to an assigned number, belonging to one thing or person, and nothing or no one else, which hardly comports with the contemporary human snowflake sensibility. Cloning is basic digital practice. Data can theoretically be infinitely reproduced. Most people on some level are freaked out by the prospect of human clones. The notion conflicts with long-standing moral or religious frameworks and mythologies. We are discussing divergent valuation formulae. From a macro-perspective, given the absolutely enormous amount of digital data, why should anyone be aggravated by a tiny bit of gone missing? It is also an issue of possession: “my” data, my own, mine. Theoretically, machines don’t own the data they process or generate. The machine operator may or may not own or possess the data his machine processes or generates. This gets us into contractual matters, about which we should confer with an expert, like Microsoft’s Bill Gates, whose huge fortune owes greatly to the concept of Intellectual Property, an area of the law that tech baron practically invented! IP is a projection of the mechanical onto the wetware that begets it. Getting back to what we believe, or think we know: We humans experience loss and machines do not; or at minimum, machines do not experience loss as we humans do. Possibly this is one reason people distrust machines. People share loss, it is one of the experiences that bind us to one another, even as it tears us asunder, one generation to the next. We also tend to become physically, emotionally and mentally bonded to what we do and what we make. Humans who experience mechanized loss are confronted with one of signature problems of the age of machines. It is a variation on the adage on problem drinking: Man makes a thing; the thing makes a thing; and the thing makes Man. This progression is a thematic undercurrent for “Occupy 2021,” but that is true in my art and life, too. The tri-axiom is a flexible word toy. You can try to insert other verbs for “make” and they change the results. You can try adding obsolete and check out what happens next.

Sideways8, “Notes on Dimensional Time,” animation still #180 (2010)

So, I have a technological communications problem. I do, and I know it, because Claude Shannon explained it concisely almost seventy-five years ago, at the beginning of his game-changing paper “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” (Reprinted with corrections from The Bell System Technical Journal, Vol. 27, pp. 379–423, 623–656, July, October, 1948):

The fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected at another point. Frequently the messages have meaning; that is they refer to or are correlated according to some system with certain physical or conceptual entities. These semantic aspects of communication are irrelevant to the engineering problem. The significant aspect is that the actual message is one selected from a set of possible messages. The system must be designed to operate for each possible selection, not just the one which will actually be chosen since this is unknown at the time of design.

Shannon’s is such a lovely thesis. He even uses James Joyce and Finnegan’s Wake to illustrate a point. How many engineers do that, these days? Shannon addresses noise, applies entropy to information sources. His graphs, equations and diagrams are incredibly elegant. The logic of his theory is palpable. My mathematical limitations prevent me from following Shannon far into his arguments, but that’s alright, because I was fortunate enough to have Friedrich Kittler explain to me the genius of Claude Shannon, in the very first seminar of my doctoral course in media philosophy at the European Graduate School, in 2010. On an intensely beautiful Alpine early summer afternoon, Kittler spoke glowingly of Shannon, his strange toy, and so on. You can watch a video version of Kittler’s lecture, which begins with an abrupt account of Allan Turing’s tragic demise (the conclusion of the morning’s session), HERE, at around the 18:55 mark, with an account of Shannon’s forgetful death. The professor’s fatalistic introduction on the “founding fathers” of the modern technological era is embedded humorously in broken English - German was his native tongue - in the remarks preceding the switch to Shannon. Kittler died not long after presenting his history of technology, from the Greeks through the present.

Kittler posing with his EGS class, 2010.

In “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” Shannon formulated the theory of data compression. Shannon established that there is a fundamental limit to lossless data compression (the entropy rate)…Shannon also developed the theory of lossy data compression. This is better known as rate-distortion theory.” [These quotes are lifted from, judging by appearances, a very old (in web age) University of Massachusetts-Lowell webpage, entitled “Theory of Data Compression," which contains a helpful synopsis of Shannon’s technical revelations. One section in particular caught my eye, and it starts, “Shannon lossless source coding theorem is based on the concept of block coding.” The section title is “Shannon Lossless Source Coding Theorem,” for those readers inclined to “jump” to the link. I am inserting this notation to introduce a comparative study within my text, of block code and what contemporary tech-artists like to call sampling (a term that carries a separate meaning in the discipline of statistics,* a meaning and field that bears heavily on our dimensional discourse in “Occupy 2021,” vis-à-vis Management practice with socioeconomic, culture-design implications on representation, as practical concept or political reality) . The key separation is motivational, the difference between loss and gain, adding and subtracting. A noteworthy extenuation is attribution, otherwise expressed as the signature. We will get to William Gates, as Kittler referred to him, later, on the related matter of intellectual property (IP) in the engineering/digital design code business. For now, we can note that Gates has moved on to advocate for IP for Big Pharma, as it pertains to the COVID vaccines, which he has championed, along with the for-profit regimes now attached to them, contributing to the artificial international disaster we are witnessing as a pandemic feature, i.e., in inequitable viral spread and medical outcomes in the global population.

I am not sure how Shannon’s brilliance informs my minor data-loss situation, how I can ameliorate my righteous frustration with a glitchy blog post-saving mechanism, although Shannon’s exact recovery sounds promising, as does a “channel of infinite capacity.” Perhaps I need a grim laugh, which the popular tech advocate Clay Shirky can be relied on to provide. I can call to mind my ostensible creative purpose as a blogger, as a free MEGAzine purveyor. I can revisit the cheery passages in Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age (2010), like this one in the “Culture” chapter, “Groups and Governance” section :

Sharing thoughts and expressions and even actions with others, possibly many others, is becoming a normal opportunity, not just for professionals and experts but for anyone who wants it. This opportunity can work on scales and over durations that were previously unimaginable. Unlike personal or communal value, public value requires not just new opportunities for old motivations; it requires governance, which is to say ways of discouraging or preventing people from wrecking either the process or the product of the group.

“Litz” series, #1352 (Digital Photograph, La Verne, CA 2005)

Only a decade after its publication to decidedly mixed reviews, Shirky’s book lands with a thud in the current social media discourse. Shirky’s perspective is a cheery contradiction to Jaron Lanier’s (continue reading), and his assessments bounce hard on the post-pandemic reality, with all we now know about the perversions of global social media, subversion of democracy, vast inequality engendered by near-completely monopolized, ubiquitous network technology and wired/wireless communications, etc. I can go for more guffaws by going “Wayback” and reviewing his prolific writings on the Internet, which date to the mid-90s. That exercise made this OG webster misty with nostalgia. Over the past twenty-five solar circuits, which equals a Bazillion Net cycles, Shirky has covered a host of tech-related subjects, with an eye toward economy and the other on culture. I would therefore hesitate to reduce his positions to a characteristic descriptor, but… lets call it “generally optimistic, verging on sunny.” Oh, those were the days! Open Source, Quake, cyberporn, Napster, weblogs, the in-room chat channel… It is somewhat nauseating to track the pundit’s pattern of advocacy for neo-liberal industrial globalization, non-regulation of “Silicon Valley,” tech-libertarian policies and asymmetrical economic models. It’s clear when Zuckerberg once again finds himself in the hot seat at the latest Congressional hearing on the latest revelation of new media malpractice, the data-powered virtual mogul thing has gotten out of hand.

The sheen of digital Pollyanna-ism is nowadays distressed, as one would say in the high-end frame finish business. The sparkly veneer is weathered, in other words, and we notice nicks, dings, pockmarks and other signs of wear and tear. The substrates are poking through the presentation coating. Or, we can use another metaphor, closer in meaning to kitsch. As the folks would put it, the digital age is a mixed bag. Today at my gym, in the locker room, an elderly fella was doing a long bit on 1-Hour Martinizing. What is it? he wondered. I mentioned that in my West Virginia hometown we had one that had been there as long as I could remember, and was still there, as far as I knew. I decided after I got dressed to Google it, and found a Wikipedia entry that filled me in on the droll history of 1-Hour Martinizing, which I shared with the man, whose name is Bruce. He is tall, strong person, who has been a bus driver, a farmer, a landowner, and much else in a rich, varied and very American life. He turned and thanked me for the information before he left, then as he was walking out the door, he said over his shoulder, I miss the mystery in life, I miss when you didn’t know things, and it was a mystery. If you really wanted to know about something, you had to go out of your way to find out. I miss that time.” In the vacuum of at-your-fingertips history, the creative imagination can swell and thrive. So can ignorance and unfounded conspiracy. Life and memories of it are now mostly digital kitsch, at one’s fingertips. What to do, what to Q?

Fifty years since the age of mail, telegrams, and telex machines, this is the era of Google's search function, social media, artificial intelligence, mass surveillance, and facial recognition. But also of misinformation: algorithmic censorship, government secrecy, fake news, WikiLeaks, and QAnon conspiracies. — Laurie Barron, “Information (Today) at Kunsthalle Basel Revisits a 1970s Classic,” Ocula Magazine, June 2021

Blue-Red Gradient (2019)

[OMG, it happened again! Another passage, expertly composed, assembled and illustrated, vanished in the Net ether for eternity! Woe and trepidation! I am recounting the incident now, days after the fact, so the upset has faded. I barely can resuscitate the memory of the gist of those paragraphs. The intricacies of the sentences, the precisely chosen verbiage, the illuminating realizations decomposed with the admission of failure to SAVE, enacted in the closing of the browser window. As if burdened by a heavy stone on my back, I noisily climbed the stairs to my wife Lauren’s office, and informed her of the disaster, exponentially worse than the last. Pouting, I honestly told her I felt like quitting. I didn’t bother to define exactly what I wished to quit. The straw. That broke. The camel’s. Back. She understands me well enough to differentiate most of the time between hyperbole, and its blasé opposite, whatever one might call the deep melancholy that transfixed my consciousness in that instant. I arose from her emerald green, uncomfortable Danish Modern work-couch, got my shit together, ate a snack and drove to the Astoria Aquatic Center for a hot tub and a swim. Upon my return, I sat in my ergonomic workstation chair-on-rollers, and began, once more to type. I am saving like a palpitatious person stricken with a weird form of OCD.]

* I wish to insert a sub-notation on the links to Wikipedia in “Occupy 2020.” The resource itself has attained a level of ubiquity in academic referencing, post-Digital Humanities. I rarely resort to it anymore. Over time one becomes aware of the foibles and value of Wikipedia, its strengths and issues. In composing a MEGAzine, a 4D blog Posithesis, I like to acknowledge Wikipedia, for its promise as an N+1-based generative local to global, personal to communal reciprocal platform. Wikipedia is likely the most well-known and -utilized expression of the “Formule : ‘N+1’” construct as posited in the original Dimensionist Manifesto, which I have written about elsewhere, so will not comment further upon here.

The Dimensionist Manifesto, 1936

(In the assured, polished manner of the TED Talker, speaking to an engaged audience.)

spindle

dwindle

∞

In the early 2010s, during one of the Arts in Bushwick-organized Bushwick Open Studio tours, Art for Humans established The Society for the Prevention of Creative Obsolescence. For those popular AIB/BOS weekends, I saw an opportunity to perform creative gestures, beyond whichever installation or mini-exhibition one might host. I am ambivalent about contemporary artist open studio tours, (AOSTs) on general principle. AOSTs have become a best practice in cultural management, a creative class attractor, an economic tool for art markets without one, or, as in Bushwick’s case, in proximity to a major market, minus robust retail infrastructure. Since America fosters only a few viable art markets, and a few dozen substantial art districts with sufficient retail concentration, mostly located in major cities, plus a few dozen artsy destination towns for the very wealthy, and as many miscellaneous cultural destinations with an art presence, AOSTs have afforded loosely networked artists, centered around studio complexes where they exist, a means to draw crowds to a short-duration event for introducing art and artist and, speculatively, generating sales. New York City in its boroughs, with its huge population of self-identifying artists (all of us are, nowadays, anyway) - estimates I’ve seen range from around 50- to well over 100000 - now boasts several of the largest, most successful. Austin, TX has an excellent one (AST). The Los Angeles metro area is home to a plethora of them. The first I heard of was the Dixon, NM AOST. An artist showing in a Santa Fe gallery in which I was employed as an installer/salesman handed me a poster he had designed for the event. One on my “bucket list” is the Laguna Beach “Pageant of the Masters,” which is part of a festival. I am a sucker for creative anachronism. I include it on this list to highlight the diversity of arts programming that fits roughly under the rubric of art tour, the studio bit being an option or afterthought. Art crawls, monthly art-nights-out, and so forth, reveal America’s ambivalence to any substantive definition of art. Of course I am ambivalent. My country’s primary concerns are commerce and real estate.

“Chase burning on Miracle Mile (painting by Alex Schaefer, originally posted on the Occupy with Art blog, September 22, 2012)”

Creative Obsolescence is a riff on Joseph Schumpeter’s conceptualization Creative Destruction, a/k/a “Schumpeter’s Gale,” which he introduced in 1942 (during WW2) in the brief chapter “The Process of Creative Destruction,” in the book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy:

The opening up of new markets, foreign or domestic, and the organizational development from the craft shop and factory to such concerns as U.S. Steel illustrate the same process of industrial mutation—if I may use that biological term—that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in.

He adds to “revolutionizes” this notation:

Those revolutions are not strictly incessant; they occur in discrete rushes which are separated from each other by spans of comparative quiet. The process as a whole works incessantly however, in the sense that there always is either revolution or absorption of the results of revolution, both together forming what are known as business cycles.

In the strictest terms I wish to assert in my statement for “Occupy 2021” that Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction is antithetical to Art, if not the artistic enterprise. The misapprehension, really a pretense predicated on a fallacy, has become a bedrock of contemporary economics, that the destructive nature of Capitalism can be construed as a creative phenomenon. The convergence of art, technological industrial monopoly for the globalization of Capital interests is fundamentally a destruction visited upon art and anyone for whom art is essential, a base trait of human existence. Capitalism and Art have no shared values. Capitalism superimposes its valuation systems upon art for venal, short-term gain, with cataclysmic destructive long- and short-term consequences for art. In this, art shares the fate of every other creative person, place and thing in our and on our planet.If this strikes the reader as a radical theoretical position, so be it. I embrace the free radical aesthetic. I have come by it the hard way, the scientific way, through trial and error. My radicalism is also experiential, if not ontological, and analytical, rooted in research and long observation. Moreover, aesthetic free radicalism must arise from the invaluable lessons and thinking of generations of philosophers, for whom art is central interest. This orientation situates art in the vocational net of wisdom, productive of visionary works. The critique and deconstruction of art to theoretical and political ends aside, free radical artists understand the phenomenon of art as dimensional, multidisciplinary and -media, initially devoid of restraint (free) but capable of progress, innovation and adaptation, rudimentary for survival, with quality of life. Our historical moment demands the declaration of free radicalism in art, which entails the legitimate destruction of economic, political myths such as creative destruction.

Original signage for 2014(?) Arts in Bushwick/Bushwick Open Studio tour AFH program, “Society for the Prevention of Creative Obsolescense (sic),” now located in the author’s mid-80s art hanging kit - still active/in use.

The Society for the Prevention of Creative Obsolescence is also a riff on the industrial practice of intentional design decay - planned obsolescence - whereby estimated product failure coincides with the release of its next iteration, the opposite of built-to-last manufacture. The technology industry is notorious for systematically gaming obsolescence to maximize profit models. The BETA release and numbered update have normalized the buggy- glitchiness of networked electronics. Consumer advocates like Ralph Nader rightly attacked manufacturers who caused harm to consumers by selling them deficient or dangerous products (most notoriously, cars). Wikipedia has a fantastic entry on Planned Obsolescence (part of its series on Anti-Consumerism) which outlines a history of PO, as well as variants: contrived durability; prevention of repairs - a big issue in the consumer tech business, but in many other products, too, like cars, tools, domestic appliances, etc.; batteries; perceived obsolescence; systemic obsolescence; programmed obsolescence; software lockout; and legal obsolescence.

However, modern technology and the whole adventure of applying creative science to business have so tremendously increased the productivity of our factories and our fields that the essential economic problem has become one of organizing buyers rather than of stimulating producers. The essential and bitter irony of the present depression lies in the fact that millions of persons are deprived of a satisfactory standard of living at a time when the granaries and warehouses of the world are overstuffed with surplus supplies, which have so broken the price level as to make new production unattractive and unprofitable…I am not advocating the total destruction of anything, with the exception of such things as are outward and useless. To start business going and employ people in the manufacture of things, it would be necessary to destroy such things in the beginning – but for the first time only. After the first sweeping up process necessary to clean away obsolete products in use today, the system would work smoothly in the future, without loss or harm to anybody. — Bernard London, “Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence” (1932)

Planned Obsolescence is a fancy name for the cheapening of everyday living and doing, a symptom of Oligopoly. Oligopoly is a fancy name for unscrupulous, greedy people and the business empires they control, manage and defend, whose malpractices they advocate for or dictate. As a user of products manufactured by companies (e.g., Apple, Toyota, Adobe, and many others), I have had numerous unhappy encounters with PO, in its multitudinous mundane expressions. PO is Standard Operating Procedure in Neoliberal society, necessary in cyclic consumption, the asymmetrical economic power churn spinning from novelty to trash. PO is essential to create mountains of garbage of great diversity, from petro-chemical to biodegradable, for the landfill or ocean disposal industry to handle. The prime beneficiaries of the oligopoly for whom PO functions stupendously well rarely directly contact the wastelands they create, nor do they mingle routinely with those who call the industrial wasteland home. Yet, the industrial oligarchs are frequently celebrated for their solutions for problems caused or worsened by the products by which they have been enriched. Often, such solutions are pegged on consumers, involve behavioral modification, depend on ideological adaptation. Oligopoly-friendly political remedies, as the most recent global ecological conference demonstrates, are impotent.

Manipulated Google Map satellite view of southern West Virginia mountaintop removal, “Notes on Dimensional Time,” animation still #110 (2010)

For twenty years, ArtReview has produced a splashy accounting of the ART WORLD INC®’s (my emphatic branding) Power 100. The industrial ranking of players and trends is an annual snapshot of the “artworld’s irrational ecosystem,” as AR describes it. The editorial process of curating the list is indecipherable, despite the selectors’ efforts to clarify. In 2020 the most powerful person in the art world is not a person, nor an entity even, but instead an obscure, buzzy-sounding designation for NFT (ERC-721), which, among other issues with the AR list, befuddled the sound mind of artnet’s Ben Davis (more on/from Ben below). For our posithetical purposes, we can at least celebrate the power of David Graeber, postmortem, lumped together with David Wengrow (co-authors of The History of Everything, 2021, which as Davis notes, is not an art book) as Thinkers - “thinker” is one of AR’s power-identifiers - at #10. Headline News: THINKERS BREAK INTO THE AR POWER-TEN! Also of posithetical note, EGS faculty Judith Butler shines at #37, for her preeminence as a gender theorist and trans rights advocate. Art-related? The rank criteria is mysterious, arbitrary, subjective, etc. Is art world power - if such a phrase has meaning - qualitative, quantifiable, ineffable, fluid, dynamic, enforceable? Maybe No, Maybe Yes, HaHa (air-kiss)! But, whatever one’s disposition in the Game, the AR list is nothing more or less than attention-grabbing power-leverage in the omni-ambiguous art whatever-it-is, ART WORLD INC®. Hoopla and glitz attach to AR’s numeric nomination of artsy potency, like clay to armature. The cavalier tone of the AR editor’s statement below is encoded artspeak. The scripted pantomime is flip, carefree, disposable, and it masks the a serious message about relevance, which is currency, which is power, or a power-sign. Also, the fiercely competitive nature of the arts and culture industry, which does orbit real political, economic and social Power. Mainly, the AR Power 100 is an obsolescence tracker, and a virtual utility as such, with some real world applications and industrial implications, with respect to, say, pricing and opportunity. And a defining citation for the ol’ CV (Curriculum Vitae). In ART WORLD INC®, who’s in and out, up and down IS the Game. The cost of playing is prohibitive, the listing exclusive, and the duration of prominence fleeting. Whatever-it-is AWINC® is nominally about art, numerically about that Bag ($), but ultimate about Attraction, an Urge, which encodes power in reproduction, without representation.

The artworld has always been a slightly irrational ecosystem in which the various competing (and sometimes intersecting) values of class, race, gender, historical and current hegemonies and conflicts, economics, ideology, national and global politics, and even old-fashioned aesthetics hold more or less sway. Sometimes (as last year) it’s informed by what’s going on in society and the world around it; at other times it seems to be almost hermetically (and wilfully) sealed from all that. Perhaps what’s most interesting as a subject of study is the way in which these various value systems adapt to or change each other. For however much we might seek to identify with or promote one set of values over another (ArtReview, for example – perhaps naively – likes to think that it operates in an artworld that isn’t governed by commerce and exchange values), as time goes by, it’s increasingly difficult to separate, completely, one set of values from another. Then again, perhaps it was always thus. — ArtReview editorial introduction to the 2021 Power 100

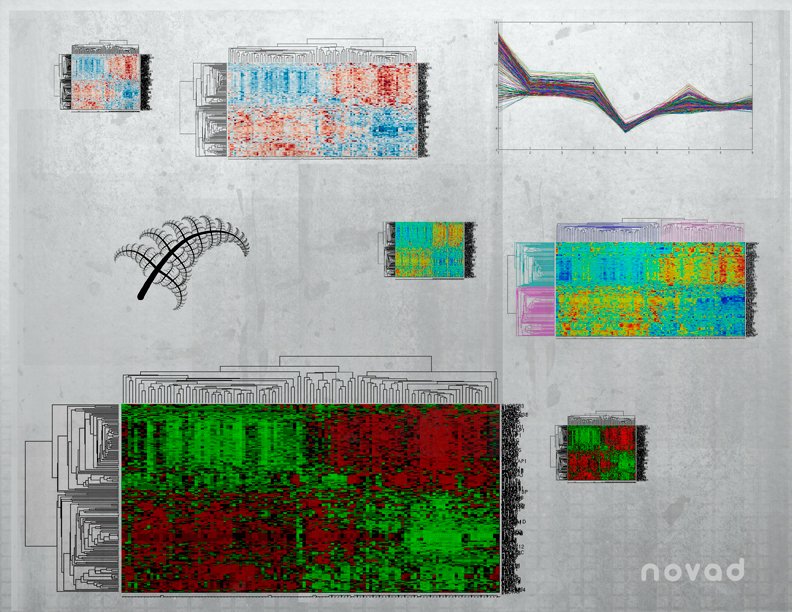

Dim Tims Power 100/cell + pattern 2021

The most successful “art stars” for the Oligarch/Oligopoly Class include Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst and KAWS, who seems to have superseded and supplanted Murikami in the visible and irrational, opaque or invisible non-ranked rankings. These “artists” practice a very sophisticated form of Creative Obsolescence (CO), which reflects the activities of their patrons, who are to varying degrees “in on the joke,” which is “on” the rest of us. The CO program typically includes: (factory-style) manufacture, supply and distribution; unprincipled (non-) attribution schemes; exploited labor; dubious claims of intellectual property; conflation of art with global industrialization; institutional, academic and media complicity or capture; extensive integration with financial sector speculation (speculators); and more. Not shockingly, Hirst and other CO art stars are testing NFT waters for opportunity. It can be argued that the NFT boom is basically tech-enabled CO. Just as blockchain technology is trending to displace or disrupt cash currency, the NFT art market is an experimental speculative instrument that is being tested for viability as an initially complementary alternative to or - in the more extreme hucksterish narratives, a replacement for - object-based art. From disruption to dissolution the macro-exchange is drifting further toward total exclusivity, perfect control, seamless conversion, cost efficiency, minimized risk and labor, maximized revenue. Intangibles, such as attaching prestige, to elevate the value of virtual ownership, are no problemas for the winning players, who rig the game to win every time. The question, What is (real) art? is made moot in the circumstances of guaranteed returns on investment, since enrichment at any expense is the rule, the only inevitable thing in this false, fake, illusory - NEW! - art domain.

In her 2011 book, Planned Obsolescence: Publishing, Technology, and the Future of the Academy Kathleen Fitzpatrick, a co-founder of MediaCommons, capably maps many of the tensions emerging from new media genres and production models sprouting pre-figuratively in the “Ivory Tower” of Higher Ed, as in the passage (p. 86) below, pertinent to “Occupy 2021, whatever-it-is, and the larger project from which it arises, my doctoral work on the Thing/Not-Thing. Fitzpatrick’s observations are relevant as subtext inasmuch as they accurately describe the perplexing academic scenario I navigated over four decades. Fitzpatrick pinpoints a structural malaise that I have found to be a persistent consternation:

Resistance to allowing scholarly production to take non-textual form runs deeply in many fields, particularly those that have long reinforced the divide between criticism (art history, literature, media studies) and practice (studio art, creative writing, media production). But one of the explicit goals of many media studies programs over the last ten years has been finding a way with the curriculum to bridge the theory-practice divide: to give our production students a rigorously critical standpoint from which to understand what they’re doing when they’re making media; to give our critical studies students a hands-on understanding of how the forms about which they’re writing come into being. And yet it remains only the rare scholar who brings criticism and production together in his or her own work — and for no small reason: faculty hired as conventional scholars are only rarely given credit toward promotion for production work; faculty hired to teach production are not always taken seriously as scholars. In fields such as media studies, we are being forced to recognize, one tenure case at a time, that the means of conducting scholarship is changing, and that the boundary between the “critical” and “creative,” if it exists at all, is arbitrary.

Green-Orange Gradient (2019)

Fitzpatrick also writes eloquently on the complexities of computerized creativity. As an OG geek, I enjoy reveling in the confusion of authorship, materialism, sentience, etc., which remains philosophically unresolved, on the relationship to the machine I use to construct and publish this blog. Fitzpatrick published her text in a moment when a prospective academic model was in play, one whose emerging protocols I was trained in at Claremont Graduate University for my Masters courses, particularly Arts Management at the Drucker school. Meanwhile, Fitzpatrick was formulating her thesis across campus at Pomona College, one of the consortium of celebrated academies located in Claremont. Digital Humanities advocates were at the time making great headway in creating contiguous remedies for the intersection of “Old” and “New” academia, which ranged from browser-based tools to systemic and institutional reformation (e.g., Zotero). It was a dynamic moment, that yielded realization and reevaluation about the interlinked projects of learning and expression, practice and theory, within the field of pedantic technology for the 21st Century. Much of the discourse revolved around the questions of how to- or how much- of the “historical” academy should be brought forward into a future, visionary version. The intervening decade (2011-2021) has seen heavy revision to the discourse, with shifts into areas of contention that were less prominent then than now, such as racial and sexual/gender representation.

On the next page (p. 87), she continues:

But there’s something more…I made a number of claims about the significance for the process of academic writing of the technological shift from the typewriter to word processor. However, that shift changed not only whose hands were on the keyboard, as well as the ways the thoughts that wind up in our texts come together, but also the very thing we wind up producing. A mildly tendentious example, perhaps, but I think a significant one: rather than putting ink onto paper, when my finger strike the keys, I’m putting pixels onto a screen — and it cannot be said clearly enough, the pixels on the screen are not my document, as anyone who has experienced a major word processor crash can attest.

Sent by friends + collectors Ann & Claire, from their adorable pad in Pittsburgh, PA. They acquired the PJM Pattern Series painting (Dr. Martin's ink & Golden/Guerra acrylic, center right) when we were neighbors in Bushwick.

Fitzpatrick rightly observes the complex activity inherent in computer-based text composition, which is dimensional and complex. The image of the text and meta-text are simultaneous within the perceptual, in the domain of visible cognition, and simultaneously extant as thought or conception being revealed through the mechanical processor. Image and representation are the medium by which thought is encoded and revealed, for the production purpose of sharing (communication, information), as output, but also sharing from the (sensual) mind of the writer to the eyes of the writer and whomever might have real-time access to the writer-user’s desktop/screen. Sensation is indelibly intimate, establishing a creative bond between computer and writer-user, which remains a unique characteristic of this vibrant personal technology. For comparison, consider the next technological development - the podcast, which can be shared as audio or audio/visual output, with an end-user; or the next, an advanced A/V-capable communications tool like ZOOM. Also, the text-only mini-share variation, like Twitter, which intensifies by reduction of the limited thought-packet (e.g., 140+ characters or whatever), which can then be daisy-chained into a string of messages to a designated set of “followers.” In the tweet-o-sphere, the consecutive or serial appearance of any thesis is compounded by the platform-as-framing-device, with its own programming and protocols. To some degree, the peculiar mech-mindfulness Fitzpatrick describes is diluted and diffused into a collective exchange in the thought-processing of reductive social media tools, sometimes with embarrassing results, as when the writer pops off with an unformed, inconsiderate idea, which is promptly witnessed by the community to which the writer-soc.med-publisher is networked:

The image of my document on the screen of my computer is only a representation, and the text that I am actually creating as I type does not, in fact, look anything like it, or like the version that finally emerges from my printer. The document that is produced from this typing is produced only with the mediation of a computer program, which translates my typing into a code that very, very few of us will ever see (except in the case of a rather unfortunate accident) and that even fewer of us could read. On some level, of course, we all know this, though we’re ordinarily exposed to the layers of code beneath the screen’s representations only in moments of crisis; computers that are functioning the way we want do so invisibly, translating what we write into something else in order to store that information, and retranslating it in order to show it back to us, whether on screen or in print.

Fitzpatrick dials in on the collaborative nature of the human-computer production in composition. The reminder that the computer is a machine must be emphasized, but the relationship is complicated by software-as-intermediary, because of the invisible linkage to the coder, without whose technical expertise the text writer’s project remains impractical, or must be relegated to an “analog” device, e.g., pen/pencil and paper or typewriter. Fitzpatrick suggests in summation a more visible form of creative collaboration between writer and coder, which could simply involve co-presentation or parallel collation, for instance:

It’s important to remain cognizant of this process of translation, because the computer is in some very material sense cowriting with us, a fact that presents us with the possibility that we might begin to look under the hood of the machine, to think about its codes as another mode of writing, and to about how we might use those codes as an explicit part of our production.

Alas, over that short decade since the publication of Planned Obsolescence, a lot has changed. Digital Humanities is pretty much obsolete, as an academic conversion movement. Post-COVID, the Academy, as such, is under significant duress. The political, economic and social trends that were already compromising and threatening the future of the academy, prior to the pandemic, have left the higher educational system on the verge of collapse, at least in terms of credibility. Among these trends: Skyrocketing tuition, student loan debt, remote learning due to the pandemic, increasing political and social polarization, downward pressures on faculty by increasingly powerful administrators, donors and boards, etc. Combined, Higher Learning, like the entire domain of education, is beset systematically, and virtuality is only one of many externalities. The Planned Obsolescence about which Fitzpatrick writes is a functionally different phenomenon from the PO engendered by Taylorism, GM’s version, or the kind engendered by Christine and J.G. Frederick in the 1920s. Nevertheless their managerial roots intertwine, and at each nexus is the schism between techne and episteme. The trend toward converting education into a cash cow for Big Business oligarchy is the most ponderous force affecting the field.

CONTENT: New River, West Virginia 2001

(In the manner of a V-log presenter, who rarely glances at the camera, while reciting from a script.)

luminescent

∞

In the immediate aftermath of Occupy, I experienced an existential crisis, which I soon discovered was fairly common among Occupiers. Through Occupy with Art, the Occupational Art School, Good Faith Space, Novads (from whom this URL + site was named), and other projects, I sought to extend the free radical movement through community networking or work-netting. I continued to exhibit my art in excellent retail galleries like SLAG Contemporary and David Lusk Gallery in Nashville. Assuming a typical Dark Matter profile, I participated in NYC panels, attended lectures and openings, visited museums and galleries and maintained a vibrant network of connections with artists, writers, performers and academics. OWS, however, had changed my understanding of most everything art-related, cultural, social, political, economic… In short my previous worldview had been made obsolete by the Occupation, and what happened to it, or what was done to it. I had to come to terms with it. My thinking underwent a substantial, if not total reformation. I was forced to reconsider, perhaps for the first time in my adult life, the precepts upon which my perceptual and aesthetic foundations had been laid. Basic assumptions about America and the world, History, money, democracy, power, freedom, technology, exchange, force, necessity, ideas, themselves, memories, etc., required a thorough “look under the hood,” as Fitzpatrick put it. The evaluation is ongoing, but I think most of the “heavy lifting” is behind me.

Occupy Wall Street

Post-Occupy, my opportunities in art world establishment channels dried up. Facing the professional artist abyss, I resorted to techniques developed parallel to my object-oriented art practice, since the mid-90s. The labor involved production of prototypical conceptual art, which was inherently obsolete or in some aspect impossible to productively manifest outside virtual media. These artworks were tactical, gestural and could be quietly confrontational. They were by definition unconventional. My lifelong ambition to succeed as an artist in the Big Apple had been gravely damaged by my radical activities. Rejected from the visible art scene on political, economic and ideological grounds, I shifted to a program of serious play. AFH projects from this period included KYSP (Kill Your Smart Phone), Selfie, Artist Zoo, and The Society for the Prevention of Creative Obsolescence. Such endeavors did not contradict ongoing collaborations with other post-Occupiers. The approach was nuanced. Presence seemed important, as did unpredictability and chaos, as means to disguise intent. I shifted from trolling corporate targets in social media to trolling Q&As at events like CAA Conference, PEN talks, Sotheby’s (Institute of Art) panels, or presentations at Cooper Union, NYPL, NYU (Hemispheric Institute), the Brooklyn Book Fair, etc. Because of my well-constructed profile, I was invited to all these things, but at the events my skin wore thin, whenever I opened my mouth. The rebuttals got testier. Eventually I took a friend’s advice and reduced my appearances to a bi-annual schedule, in the interests of stress-reduction and anger management. My performances were being mistakenly construed as real, but disruptive, when they were only “art.” I mapped the contours of my blacklisting by a dimensional approach, which involved submitting dozens of professional applications, and whenever possible, using contacts within the bodies or businesses to which I applied to discover the circumstances of my near-total record of rejection. I had been fortunate, previous to OWS, to have enjoyed enough professional success, production experience and network affiliations to be able to distinguish artificial obstacles from reasoned inadequacy, e.g., lack of- or too much experience for the position, mismatched cost/productivity expectations of/for the hire, managerial concerns about personality defects, ageism and similar excuses for “bad fits,” etc. I worked with high-performing technicians to analyze and where possible correct the virtual destruction visited upon the AFH platform, consequent to my Occupy involvements. Management pretensions of objectivity became increasingly, subjectively, irritating. For me, the work of Kafka became more literal, non-fictional, horrible.

Daniel Beatty Garcia: In your work this incomprehension in the face of the nonhuman world is the nexus between horror and philosophy.

Eugene Thacker: There’s a synergy between that kind of cosmic horror and certain philosophers who also explore the limits of our understanding. When we think about philosophy we usually think about some sort of picture of the world, and when we think about philosophers, we think about a person who knows, and who’s going to tell us how to live our lives and how to exist in the world and so on. But some philosophers are more interested in asking questions than giving answers, and finding compelling ways to articulate confusion. — MONSTROUS THOUGHTS: Philosopher Eugene Thacker on the “New Golden Age of Horror,” 032c (July 16, 2019)

Most importantly I tried my best not to personalize my enforced redundancy. No matter how much effort I applied, I had to admit there would be no straightforward, linear, advancement on the career path I had been traversing for nigh twenty years. The gates had been shut and would not re-open. My trajectory would have to be adaptive, circuitous, oblique. Was this a new development? Not so much, but the stakes felt higher. My Occupation had made my occupation untenable, and I resorted to responsive asymmetry. I experimented with multiple configurations of virtual/actual production, arrayed on intersecting multi-dimensional grids or networks, seeking communities for whom my Occupier resume was either an asset or at least not a liability. Some of these attempts met with a modicum of success, but that term (success) was now relative in a way it hadn’t been before. I resolved not to be overwhelmed with bitterness over the harsh facts of Occupy’s demise, and those who cynically skipped through the ruins of the movement, whose fortunes were made by staying quiet throughout the uprising, affirming their affinity with the “winning” side, or worst of all, those who used Occupy as a professional springboard. I had to take a look at the principles in victory and defeat, and what I learned about people I have yet to unlearn. My regard for the people, particularly for the people I believed art was for, had been dealt a devastating blow. The most important lesson I learned, though - and this has to do with obsolescence and the radical distinction between humans and machines - unlike a widget, I could refuse to be made obsolete. By any means available, I could resist enforced or any other kind of obsolescence, except one: physical aging, which is its natural analog… Or to be more nuanced on a touchy subject, I could resist or deny aging, but the biology is conclusive. I must age and my body eventually dies, if it is not killed in the meantime.

Actual phone, as described in the introductory prospectus for “Kill Your Smart Phone [KYSP] (Photo: LULA)

My refutation of obsolescence centered the next steps in the strategic progression. I reformulated my approach to selling art, looking toward the next generations of art collectors. I experimented with various new online art marketplaces, notifications for which seemed to cascade through my inbox and feeds hourly. AFH first offered PJM art online on ETSY circa 2001, and with Saatchi, when it launched, then Artsy in its first wave, and others, with little or no response. We conceived of and tested our own virtual sales platforms, but none of these replaced or displaced person-to-person sales, either direct or through dealers and galleries. Back then, buyers and sellers were reticent to purchase stuff online, generally, and art especially. Amazon changed everything. As the virtual sales behemoth consumed vast portions of the Net-based retail space, consumer comfort levels improved incrementally. Finally, the conversion from real world to virtual shopping escalated toward a game-changer, the tipping point, during the pandemic. The art world was very slow to adapt, but today most major outlets have a legitimate web-sales program. Outside the structurally established hybrid art business, and the now-technologically-refined top-tier exchanges for all kinds of cultural production, including “art,” there are a host of specialty platforms focused on specific consumer demographics. I scanned and sorted through a host of early options (including Kevin McCoy’s blockchain project, shortly after its launch), and, after trying some, stepped away from the domain, choosing to maintain only our store at Good Faith Space. Even before NFTs became the Next Big Thing, the disjuncture between Art and whatever-it-is, virtualized art is in my estimation still a problem of critical insufficiency on the virtual side of things. One positive outcome of the COVID-19 global epidemic is the unmasking of this insufficiency. My first priority as an artist is to create art for humans - not machines or any other thing. Period. Which is out of step with what’s going on with AWINC®.

When things are confused and confusing, it can help to survey and scan the domain and gather a few quality perspectives. Timing is important. You have to know your go-to sources. One of the best analyses of the whatever-it-is phenomenon is McKenzie Wark’s “Digital Provenance and the Artwork as Derivative,” which e-flux published in 2016 (Issue #77, November). She begins by framing one of the key issues thusly:

Let’s start with this paradox. Art is about rarity, about things that are unique and special and cannot be duplicated. And yet the technologies of our time are all about duplication, copies, about information that is not really special at all. At first, it might appear that the traditional form of art is obsolete. If it has value, it is as something from a past way of life, before information technology took over. But actually, what appears to be happening is stranger than that. Let’s look at some of the special ways in which art as rarity interacts now in novel ways with information as plenty, producing some rather striking opportunities to create value.

CONTENT: Jessica & Friend, Nashville 2001

She goes on to sketch the key connections among a matrix of factors which pose in aggregate an existential crisis for artists and art in the post-contemporary scenario. Wark lucidly explains the interplay of derivatives and simulations, a gamed which becomes very complicated in a few moves, then she draws out the appropriate associations, whether economic or theoretical. To get to the core, she dissects the parts, a progressive, if clinical, approach for aesthetic/economic/technical deconstruction. Wark concludes:

So in short, I think what is most interesting about the relation between art and information is the reciprocal relation between art as rarity and information as ubiquity. It turns out that ubiquity can be a kind of distributed provenance, of which the artwork itself is the derivative. The artwork is then ideally a portfolio of different kinds of simulated value, the mixture of which can be a long-term hedge against the risks of various kinds of simulated value falling—such as the revealing of the name of a hidden artist, or the decline of the intellectual discourse on which the work depended, or the artist falling into banality and overproduction.

In late 2015 I ceased art production and devoted myself to doctoral work on the dissertation, the thesis of which would ultimately become A Thing [There Is No Such Thing]. In the course of writing and illustrating the 700+ page text by hand over eighteen months, I continued to explore the in-flux field of art, with an eye toward the hybridization (virtual/actual) of art, through parallels, primarily economic-aesthetic, unfolding in conjunction with macro-, global or universal changes over time. The picture that began to emerge was a vision of the future for art, based on the study of patterns recognizable at all levels of exchange. Roughly, the future for art would be a conglomerate for the top tier transactions now conducted through the Big Enterprises, such as Gagosian, Pace, Hauser & Wirth, Lehman-Maupin, Perrotin, David Zwirner, White Cube, et al., and the worldwide network of art fairs. Art fairs would consolidate into a single network, with subsidiaries and constellations. The network of annualized expositions would continue to exist as a syndicate of affiliates (like US college football bowl games) with corporate sponsors. Museums would adhere to this model, with a few exceptions, perhaps, in the case of the NY Metropolitan, the Pompidou, the Tate and a few others. China will probably its own mirror version of this system, which will eventually be subsumed, consumed or enjoined to the West’s. Auction houses will continue to lead the secondary market, but eventually a single entity will acquire and conjoin all of them, under one ownership entity. Amazon will supersede all these exchanges, and at last monopolize the global marketplace small-to-large.

Fletcher Liegerot performing in "Artist Zoo" > Arts in Bushwick/Bushwick Open Studios (2014) in AFHstudioBK

The reduction of aesthetics to subservience of this whatever-you-call-it has in great measure already happened. The NGO support systems - the foundations, the art-orgs, the non-profits, etc. - will continue with superficial autonomy, but their reliance on corporate/elite patronage will govern their productive capacity, which limits the function of these entities to the effectiveness of the tax breaks they provide their well-heeled benefactors. They too at last will be integrated into the approved hierarchy, one by one, or they well disappear. The rich have a panoply of implements to evade or avoid taxation, as we learned through leaks and investigative journalism (see the Panama and Pandora Papers). State-sponsored art programs and their brick-and-mortar infrastructure will suffer the fate of the states, themselves. Amazon, or whatever banal name it acquires (i.e., Alphabet or META), when it merges with Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Google, plus the anagram corporations and agencies i.e., ATT, IBM, CIA) into the singular global power, with or without China, will make the State obsolete, will be the single state dominating the human population, using acquired force, surveillance, imprisonment and all other means to maintain its power. The most powerful players will dedicate themselves to ventures like off-worlding and immortalizing themselves through bio-technology, etc. Art will be only one luxury asset they enjoy. Star artists will cycle like production auto vehicles do, which is predominantly the case already. Art trading will continue to be the risk-minimal or rigged speculation it is already, at the art industry pinnacle. The rest of the lower-case art industry will cater to order-fulfillment for popular tastes, which is to say, follow the consumption models that exist for rugs and shoes.

(In the manner of a poet giving a reading at a coffee house or local.)

needle

No-one would listen to his theories: no-one was interested in art. The young men in the college regarded art as a continental vice and they said in effect, “If we must have art are there not enough subjects in Holy Writ?” — for an artist with them was a man who painted pictures. It was a bad sign for a young man to show interest in anything but his examinations or his prospective 'job.’ It was all very well to be able to talk about it but really art was all ‘rot’: besides it was probably immoral; they knew (or, at least, they had heard) about studios. They didn’t want that kind of thing in their country. Talk about beauty, talk about rhythms, talk about esthetic — they knew what all the fine talk covered. One day a big countrified student came over to Stephen and asked:

— Tell us, aren’t you an artist?

Stephen gazed at the idea-proof young man, without answering.

— Because if you are why don’t you wear your hair long?

A few bystanders laughed at this and Stephen wondered for which of the learned professions the young man's father designed him. -- (p. 34,) James Joyce, Stephen Hero, manuscript published after the author’s death, 1944

(In the manner of a mid-career lecturer at University, with slideshow.)

finesse

∞

What is to become of us artists? It is facile to say that almost all our prospects are grim, but this is true is on a number of levels, demonstrable in a range of metrics, readily available through the art industrial media (e.g., Artnet news). Disengagement remains the first option, which is always true. The concept of an artist strike is clumsy and comical, readily evoking the “If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it…” reposte, unless the artist-striker is positioned to draw attention to the stand. However, dismissing the tactic outright ignore the studio artist production discipline of intentional isolation, in order to maximize focus in labor and thought. As much as the practical aspects of artist isolation have been fashioned into the butt of cliche, the non-artist understanding of its (isolation’s) necessity for art excellence is rooted in fear of art, its mystery, its unknowns, and its polyvalent potential. The invisible or socially camouflaged artist playing the art historical long game has enough precedence, the current revival for female (e.g., Hilda af Klint), BIPOC, LGBT+ and other identity-artists - not-White-Euro-Male-Hetero - is the preeminent push currently and proof of point. The future of the artist is being designed before our eyes, right now, and along with it, art’s future definition, or continued de-definition.

Matterhorn Project: "IN GOD WE TRUST" (Bushwick - Livin' the Dream!) ~ October, 2014

The terms art and artist are already nearly completely fungible in the popular imagination. Art amounts to whatever one does or makes to which one attaches feelings like pride and accomplishment, or anything one does or makes that is not otherwise categorizable. For Big A art, art is whatever one of that tiny club deems it, or buys as art, and what the super-rich art club AWINC® collectively accepts as art. An artist is who such a one or collective of them determines to be an artist. The procedure for minting A-list artists is as transparent as cryptocurrency. An authoritative purveyor can determine someone to be a viable artist, provided the collector class can be convinced. Some weight is still given to the opinions of the few remaining celebrity critics, like Saltz and Smith, but that’s soon over. The link between AWINC® and cryptocurrency is a curious one. The art-NFT (Non-Fungible-Token) boom-craze is loudly touted by advocates as a bonafide future for art and artist. My friend, former ArtInfo editor, current artnet Editor-at-Large Ben Davis has been following the phenomenon, and has yet to make up his mind about NFTs, after attending the sold-out NFT.NYC 2021 conference. He writes:

On the one hand, I find it indisputable that the NFT/crypto-art space is heavily driven by FOMO, hype, get-rich-quick fantasies, strategic double-speak, and fake-it-til-you-make-it auto-hypnosis. On the other hand, much of the same applies to the worst of the “traditional” art world. Which of the two has the deeper deep end or the shallower shallow end is hard to say…

Above all, I left the three days of events during the conference convinced that the NFT-powered “Web 3” is coming. It’s not something you are going to escape hearing more about, because huge forces are propelling it: a “take-back-the-web” backlash against the current internet order, which in the 20 years since Napster, has destroyed the commercial basis for most creative careers; some genuine youth cultural foment from digital natives exuberant to see memes and gifs* valued; the worldwide displacement of attention into online spaces that came with last year’s Covid quarantine; and, above all, financial capital’s desperate, win-at-any-cost hunt to invent new avenues of return in an economy that has been leeched of plausible investment opportunities by more than a decade of near-zero interest rates and global stagnation.

*[Follow the internal link to a June 2021 Guardian article by Sirin Kale, “NFTs and me: meet the people trying to sell their memes for millions,” which provides helpful context for art-NFT discussion, within the broader domain of online culture and economics.]

Screen grab of AFH Not-an-Artist (NAA) Tumblr (April 1, 2014)

I used to cite Greg Sholette’s excellent book Dark Matter as a discursive basis, a point of origin, for conversation on art economy, specifically labor, but much has changed since its publication in 2011. The pandemic has deeply impacted art workers, who suffered disproportionately compared to other economic sectors, through job loss or layoffs, temporary workplace shutdowns and permanent closures. Good benefits are a rarity in the art business, usually only reserved for executive administration and owners. Those in art-related labor services infected by COVID-19 in the US had to face added horrors atop the illness, as did the population in general, navigating the already broken, now overwhelmed, for-profit health care system. I also used to cite the Handbook on the Economics of Art and Culture, Volume 1 particularly a study breaking down the answer to the question commonly posed by snarky art tourists and baffled wannabe art pros, “Is this how you make a living?” or, for the latter cohort, “How can you make a living doing this?” [The short answer would be, “Whatever it takes”]:

Studies of artistic occupations show how artists can be induced to face the constraints of a rationed labor market and how they learn to manage risky careers. Pioneering empirical research by Baumol and Bowen (1966) found that artists may improve their economic situation in three main ways which are not incompatible and may be combined: artists can be supported by private sources (working spouse, family or friends) or by public sources (subsidies, grants and commissions from the state, sponsorship from foundations or corporations, and other transfer income from social and unemployment insurance); they can work in cooperative-like associations by pooling and sharing their income and by design a sort of mutual insurance scheme; and finally they can hold multiple jobs. — P.M. Menger, “Managing the risks of the trade,” Ch. 22, “Artistic Labor Markets,” HotEoAaC, p. 794

Post-Occupy, post-pandemic, Menger’s framing of the asymmetry inherent in the plight of the professional,semi-pro or struggling, aspirational artist is tone-deaf. Top-down inducements, exhortation of careerism, acknowledgement and acceptance of constraints and rationing, hawking self-management - the legitimacy of these admonishments largely expired during the Crash of 2007-8 and through the Great Recession. The onset of Corona Virus added new layers of art-labor disenfranchisement. The definition of art and art-related work as non-essential condemned the sector to the margins. Cultural professions on the whole suffered the strains of the dramatically precarious. If we examine the macroeconomic topology for the arts since 1966, when Baumol and Bowen did their research, the ascribed techniques for artist survival mapped in HotEoAaC are mythical. Since the mid60s, the cost of living for 99%ers (including almost all artists) has skyrocketed. The pay flat-lined.

“Time Structure #27” (2018)

It was a reaction to this economic reality, interwoven with the ideological scarcity principles predominant in AWINC®, which drove artists like myself to collectivize (see DDDD and 01, AFH, et al.). The phenomenon had its precursors, but the shape of the neo-collective movement is inter-dimensional, extending across and within blurring sectors (economic, social, governmental). The shape of these collective formations fluctuates internally and externally. In some aspects, the neo-collectives mimic corporations, while maintaining viability for individual accomplishment within their frameworks, and beyond them. In an artnet interview, two of the co-founders of Meow Wolf gush about the messiness of the configuration, and the conflicts presented within the quasi-art construct. This conversation represents a mindset that deflates other models of art industry and production, including the definitions of success:

Do you think you will ever have a Meow Wolf museum show?

Di Ianni: Maybe!

King: If the right situation presents itself, yeah. Right after the house opened, I was working the front desk and a woman came in and said, “I’m from the Art Institute of Chicago.” I was like, “Oh sweet, let us know what you think.” And she literally went in and five minutes later she walked out of the exhibition, threw her hands in the air, exclaimed across the entire lobby, “Where’s all the art?” and walked out.

That is some people’s mindset, right? They see what we are doing as not being aligned with everything they personally believe to be art. And that’s totally fine. Art is subjective. You don’t have to think what we’re doing is art. When I sit in fucking meetings and I look at spreadsheets, I don’t even always think what we are doing is art, right?

Our intention purely is to be expressive of our condition and our thoughts and the times that we live in, and that resonates to me in the way that art has always done throughout history.

Di Ianni: We were talking earlier about what happens when you leave this place. If we can get somebody to look at a piece of trash differently, or think differently about what a parking meter does, or like, solve climate change, that’s all part of the same kind of process of activating your imagination and connecting to the human condition that I think maybe is art.

If everybody doesn’t connect to that, if people need a white cube gallery to call it art, that’s fine. And there’s a place for that. I’m not anti-art world.

King: Neither am I!

Di Ianni: It’s just nuanced, right? There’s such a tendency to have black and white conversations about stuff, but it’s not so dualistic. The whole thing is an art project—the organization, the company, the business, the relationship with the union. This is what we do. It’s all part of the art project. — “‘The Whole Thing Is an Art Project’: Meow Wolf Cofounders Explain the Grand Plan Behind Their Wildly Popular Immersive Art Universe” by Sarah Coscone for artnet (October 20, 2021)