By Paul McLean

Photos by Trey Mitchell (2001)

NOTE: This essay is in BETA. I will be adding links, correcting grammar and typos, doing some additional light editing for content, making a list of references, etc., while “The Key Show” at Zeitgeist Gallery is on view. If you have any questions about the essay, want to bring my attention to mistakes or omissions, or have helpful suggestions, please don’t hesitate to drop me a line or add a comment below the text. I hope you enjoy “My Chestnut Experience!” - PJM, 5.29.2024, Astoria, OR.

INTRODUCTION

1

A quarter-century has passed, since I first occupied studio space at Chestnut Square, an occupation lasting a handful of years. For me it was a period of tremendous creative productivity, involving lots of activity on many fronts, generating memorable episodes of great variety. Through the fog of memory, some impressions from this creatively fertile time stand out more than others. Among these a few of those impressions warrant chronicling here, with the caveat my anecdote selection process will be entirely subjective. I hope by sharing my stories I can offer a meaningful contribution to “The Key Show” exhibition hosted by Zeitgeist, linking the building, the people and moment with current efforts to nurture artistic community in Nashville. In “The Chestnut Experience” I’ll also share observations and opinions on a range of issues I hope readers find relevant and/or interesting.

Made at Chestnut: “White Cube” - Golden acrylic paint in hand-finished MDF container (PJM and Eric Johnston, 2000); presented on lead-wrapped wood, Astoria, OR, for “End of the West” installation (2018)

2

For context, on either side of Y2K The Music City, and by extension, the USA, were undergoing monumental changes. Politics, technology, economics and culture were in a state of flux. Between the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, and the horrific fracture that was 9/11 the world entered a phase of upheaval that I would characterize as the fraying of historical fabric at the macro level. Generational narratives seemed resolved or obsolete. If only briefly, the conflagrations and angst of the 20th Century one felt might give way to a new, promising reality. Advances in personal computing and network communications precipitated the massive restructuring of society and all its sectors, a trend continuing through the present day. Dynamic changes material and virtual accelerated dimensionally, local to global, affecting us individually and collectively. In short, from history’s ashes, Mankind was poised to move out from the mushroom-cloud-shaped shadow of nuclear war, leaving behind us nightmares of worldwide cataclysm, toward a tech-enabled dreamy future utopia of novel ideas and experience. It was a fun mirage, while it lasted.

Most of us hadn’t yet realized that the seeds for rampant inequality and political polarization had been planted already in the shabby and burnt-out remnants of the Old World Order. We didn’t comprehend how fragile the situation was, and that cascades of crisis would soon upend the potential future we glimpsed. After 9/11 Philosopher Jean Baudrillard wrote in his controversial essay, “The Spirit of Terrorism,” “The whole play of history and power is disrupted by this event, but so, too, are the conditions of analysis. You have to take your time. While events were stagnating (in the 90s), you had to anticipate and move more quickly than they did. But when they speed up this much, you have to move more slowly — though without allowing yourself to be buried beneath a welter of words, or the gathering clouds of war, and preserving intact the unforgettable incandescence of the images.”

Remember? It was the Clintons versus Gingrich, Armey and DeLay, the rise of the Moral Majority and Christian Nationalism, rallying against abortion rights as the central organizing drive pushing the culture wars. Tipper Gore versus obscene rock and rap. Campaigns against publicly-funded art, leading to the Mapplethorpe, Serrano and Ofili scandals. The empowerment of Neo-cons and neoliberals, corporate syndicates and their globalist advocates, platformed at the World Economic Forum in Davos and girded by think-tank-proliferated Management theory. Then, Bush v. Gore, and the turn toward China, away from Japanese industrial might. On the horizon was Citizens United, and the incremental removal of safeguards to protect us against monopolies, privatization and consolidation. In Silicon Valley, the tech miracle was already moving in a much darker direction, in the wake of the dot.com crash. The nerdy hippies were getting greedy and power-mad. The country was being torn apart by conflicting ideologies and a predatory winner-take-all economy was fueling the fires of discord. Fox News and conservative talk radio were radicalizing half a generation, while the other half after the “Me Decade” further receded into a quagmire of narcissism, under the banner of Self-actualization and Identity.

If 9/11 marked the shockingly abrupt end of the modern and contemporary eras, or the beginning of the madness and excess defining the first quarter of the 21st century, the decade prior to 9/11 resists demarcation and definition. To call that decade complicated is insufficient. The threads of meaning intertwining and unwinding in the 90s and early 00s must be recovered and re-assembled in order to get at the truth of recent phenomena, like “fake news.” When we look back now on that fraught and febrile time, we notice that patterns were emerging, subtle shifts in the logic of things, a new questioning of the concrete and immaterial nature of existence over time. While this convolution had much to do with the arrival of ubiquitous digital media in all its manifestations, it is key to note that other drivers operated then to either determine or subvert the unavoidable change that was happening. Some of us in places like Chestnut (there were other such nodes across America and beyond our shores, it turns out) were trying to make sense of it all, in Real Time. Through the arts and creative life. We would soon find out about each other via the Internet, but also through traditional, analog channels. We didn’t realize until too late how naive we were, which is not meant as an indictment or pejorative.

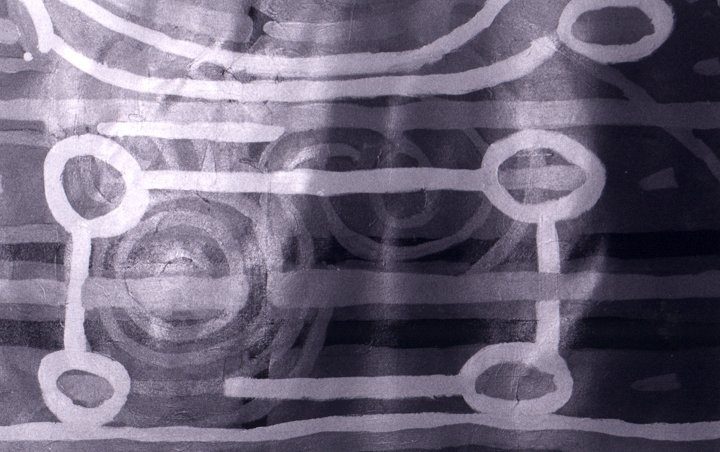

"N-substantiation"Currents,” Flow and Reproduction Series #41, 4D Quantities Series #4, 12" x 9", Flashe Vinyl on Canvas, 2019

3

Fast-forward to 2024. Without fretting much about who the “we” is for a minute, where do we stand? I propose that we are in the post-contemporary period now. That term (post-contemporary) is not my invention, but for the sake of situating my discussion of civilization at scale, from big to little, establishing a platform for my remarks and the underpinning analysis matters, at least for my purposes. Not only is it a matter of logics, it is a question of physics and nature, pertaining to humanity and our perceptions. My essay will have elements of reflection in it, but not only those. The timing of the invitation — to write about the Chestnut experience — for me is fortunate on several levels.

Rather than attempt to elaborate on the above paragraph, I obliquely recommend readers familiarize themselves with the thinking Liam Gillick is doing on the subject, for instance in his 2010 essay “Contemporary Art Does Not Account for that Which is Taking Place,” and in his 2020 dialogue with J.J. Charlesworth in ArtReview (“Is This the End of Contemporary Art As We Know It?”) . Then, I’ll make an elliptical move and point to an illustration of my preoccupations. My example is Return to Reason: Four Films by Man Ray. Jim Jarmusch and Carter Logan (SQÜRL) reconstituted the selection of moving images by Ray originally made in the 1920s with an audio soundscape. The derivative assemblage was reformatted using the latest cinematic (digital + analog) technologies. What is Return to Reason illustrating? Many things, but we can focus on a few.

The inherent looping power of the time-based media (resonance)

The nature of artistic reproduction in the 21st Century (the mechanical)

Collaborative and cross-disciplinary practice as a woven form (twining)

The peculiarity of language transiting through the post-contemporary

The durability of the subject and object of human vision, in and of art (the perceptual attraction)

The conjunctive presence of architecture (form) and concept (virtuality) vital to post-contemporary composition

In my estimation, this list helps explain what was going on at Chestnut during my stint there, but also what was up more generally. To expand the orientation, we can imagine a process of mapping connections among events, on the basis of relevance. I am going to draw here on my old friend Bob Solomon’s (producer Woodland Studios — if you know, you know) non-binary affection for both reverb and echo. On my map of the Chestnut Experience, which (the virtual map) is to a degree chronological, I am placing a pin in 1928. That pin placement is a bit arbitrary, within the brackets of Man Ray’s movies, as re-presented in the 2023 derivative (released on the 100th anniversary of the original Return to Reason). The 1928 marker prefaces the great Wall Street Crash of 1929, and splits the phase between the end of WW1 (1918) and the beginning of WW2 (1939). A (re-)viewing of Man Ray’s four films is inflected by these serial events/disasters.

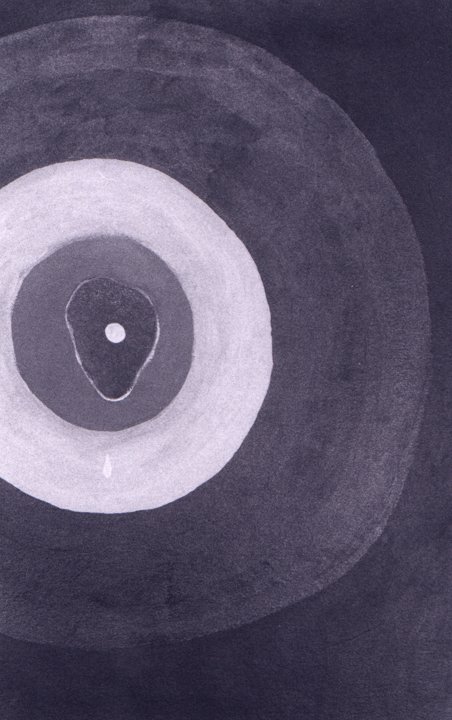

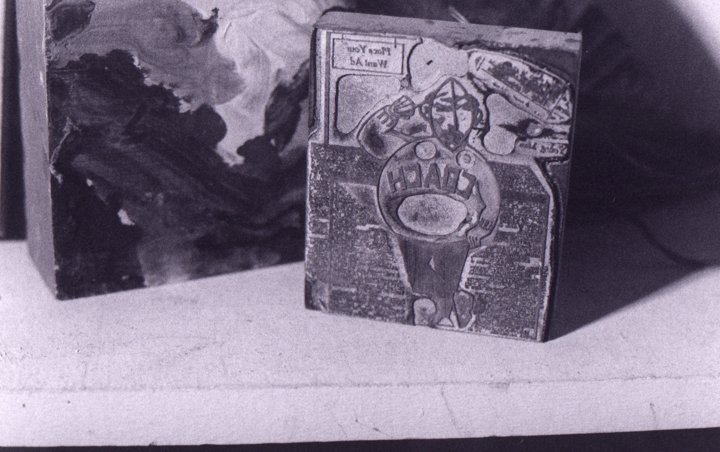

Made at Chestnut: “01” cut-vinyl adhesive on 12” vinyl record (PJM, for “Heartless01”)

Spinning the wheels of time forward, another pin is placed at Y2K, which I identify as the inception of the post-contemporary period. The most important feature of Y2K? It was an event that never happened. However, in the history of network computing, the question is whether Y2K as a media technology phenomenon was an early indicator of the global transformation by electronics and communication that coalesced in the aftermath of 9/11. I am referring not only to the emergence of Web 2.0, but also the vast expansion of surveillance enabled by the new digital social realities, as well as the fundamental alteration of economics and markets Big Tech facilitated. By 2007-8 and the onset of The Great Recession the seeds of dimensional crisis planted in the 80s and 90s were bearing their toxic fruit.

A pin to mark the posterior border of our map is the easiest to place. It goes in at June 2024 at the opening of The Key Show. At the end of 90s, when I had a studio at Chestnut and was living the artist life in Nashville, such as it was, I don’t remember any foreboding that the world would soon descend into a prolonged struggle, within which the very definition of civilization significantly dissolved. I know that, while watching the collapse of the Twin Towers on a screen at Fido with dozens of people, I was aware that everything had changed. None of us at the time could have imagined how drastic that change would be, and how far in all directions its reach would extend.

Watching Return to Reason I got the impression the artists involved were operating in dimensionally resonant circumstances. I felt affinity with their mindset, as expressed through creative decisions, symbols, settings, props, costumes, experiments, editing and so on. Reflecting on my artistic production and the ideas cycling through the output from the mid-90s through the early 00s, I am wondering whether those times have something to tell us about the current moment (2024). I am wondering whether, within our post-contemporary connecting-dots chrono-/topological game above, we prefigured a grim possible future, one closer than it appears in the rearview mirrors. I shouldn’t be surprised, if so. Artists are always the canaries in the coal mine of human strife and derangement. We are the oracle seldom heeded. But also the timeless tinkers whose inventions prefigure the worlds to come, or that might have been.

Studio view, circa 2001 (PJM)

IN BROAD STROKES: THE NASHVILLE ART SCENE, CIRCA ’95-6

4

I rolled into Nashville in ’96 with a headful of artsy steam and a new bride, on the heels of an extended creative run (doubling as a honeymoon) in Scotland, preceded by a decade embedded in the Santa Fe art scene and market, which then was competing with LA for second place in the standings behind New York City, in terms of sales and cultural heft. In Santa Fe, where I landed after undergrad studies at Notre Dame, I had learned to hustle, maintaining a prolific painting practice, networking, working in and with galleries and art support businesses, and writing. The cost of living in Santa Fe was comparatively high, and the property values were through the roof. Arriving in the Music City, I was shocked at how affordable everything was. At once I got to hunting for a studio and a place to live. In short order, I found both.

It hadn’t taken long to get the lay of the land, art-wise. Nashville was what I would call an open market. In spite of a mid-size American city population (about a million souls), Nashville had an oversized media profile, due in large measure to the flourishing country music industry. The visual art infrastructure, however, was limited to a dozen or so retail galleries, a couple of museums, the programs at Vanderbilt, Fisk, Watkins and the Tennessee Arts Commission, interesting pop-up and alt.art collective projects, plus odds and ends. Some artists — Somers Randolph, Alan LeQuire, Paul Harmon, and Myles Maillie — had garnered attention and followings, though by divergent means and methods

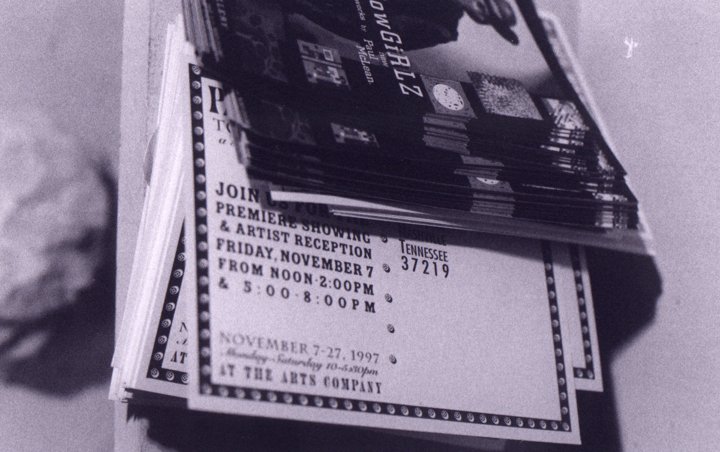

The scene was de-centralized and siloed. Cumberland Gallery and Cheekwood catered to the sensibilities of Belle and West Meade, Green Hills, Franklin and their enclaves. Zeitgeist and Hillsboro Village were pretty popping, drawing crowds from the colleges, the businesses on Music Row, and other constituencies in the West End and 8th-12th corridors. Downtown and East Nashville were in the early stages of a substantial development expansion/transition phase. Arts Company was making the most of a bric-a-brac approach, and In the Gallery in Germantown was focused on African arts and Black artists, primarily. Local Color had a pay-to-play set-up in Midtown. Aside from this, not a lot was happening, certainly nothing cohesive.

Made at Chestnut: “Growing Things” - acrylic on canvas, for “Jewels of the Nagas” at Yoga Source (2001)

I would soon discover after a bit of digging that Nashvillians serious about collecting art were mostly shopping elsewhere. Traditional Southern salon-style showings still were happening in people’s homes, conducted by trusted intermediaries or consultants. Benefit auctions were a preferred way to nab a piece by a favored local artist, usually at a discount price. ‘Exposure” was a word bandied about. An artist was expected to do routine free stuff. Also, there was nomenclature confusion. if one self-identified as an artist, a common response might be, “Oh, really? What do you play? Are you in a band?” Yet, I discerned in my early days in Nashville a genuine hunger, interest and enthusiasm for visual arts in the community.. I sensed the potential for transformation across the cultural spectrum. The conditions were right.

First, Nashville was booming, but also had substantial anchor economics. HCA was emerging as a major force in corporate consolidated or managed medicine. Ingram, an industrial giant, was solid across its diverse portfolio. Nashville was regional center for publishing, design, post-production and printing houses. Country Music was a global phenomenon, with an enormous fan base. These and other factors were contributing to the city’s makeover. Suburbs were starting to sprout in every direction. Gentrification was altering many of Nashville’s neighborhoods and whole sectors of the city. Sprawl and gnarled traffic were the downside, but it was nothing compared to NYC’s and LA’s. Nashville was becoming a Creative Class model destination. At the cultural core was a unique receptivity to collaboration, owing to the musical traditions convergent in Nashville.

CHESTNUTS

5

Through word of mouth, I got together with sculptor and jeweler Somers Randolph, whose coffee shop Blue Sky Court and Untitled efforts had helped to shape awareness of the importance of art for art’s sake in Nashville. “Fear No Art” bumper stickers were common. Through his projects and art-related organizing, Somers demonstrated the value of art entrepreneurship, using his oversized personality and connections to bridge divides among business leadership, artists, collectors and civic entities. Somers had hatched a plan with John Reed to carve out studios on Chestnut’s first floor, and I agreed to join them in the endeavor. The building tenants already included a few other artists, such as Joe Sorci and jack-of-all-trades Foster Jones, but the bulk of the other occupants were engaged in everything from selling furniture or cabinet-making, fabrics, to commercial art and so on. It was a hodge podge, a melange of folks and professions.

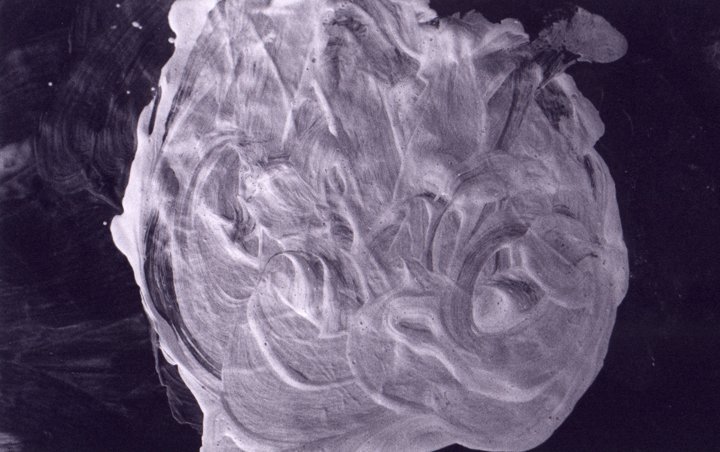

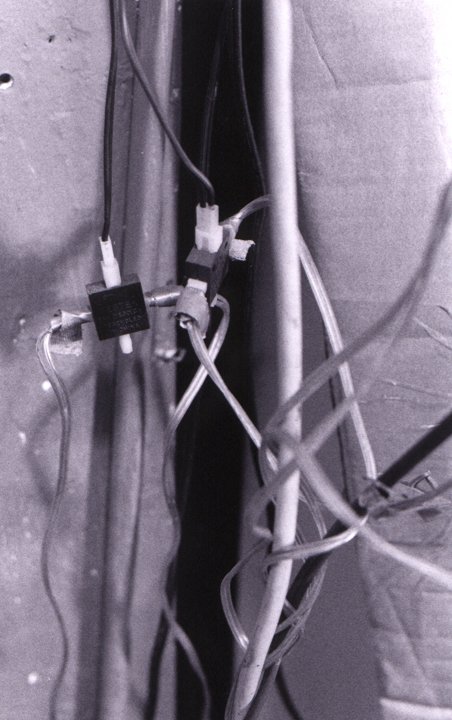

Chestnut Square (formerly May Hosiery Mills), like many old, converted and subdivided factory buildings and industrial complexes across the country, has a remarkable history. At one time May was the biggest employer in the city. By the mid-90s, it was a red brick shell, on the verge of dilapidation. It had no central heating or cooling. The plumbing and lighting/electrical system was a mess. It had a single working freight elevator. The loading dock was an endless source of territorial contention. Tenants were expected to solve their own garbage needs, for the most part. One heard about break-ins and thefts, and we were warned about the criminal elements who were malingering about. Telephone service was not provided, and not a simple matter to obtain.

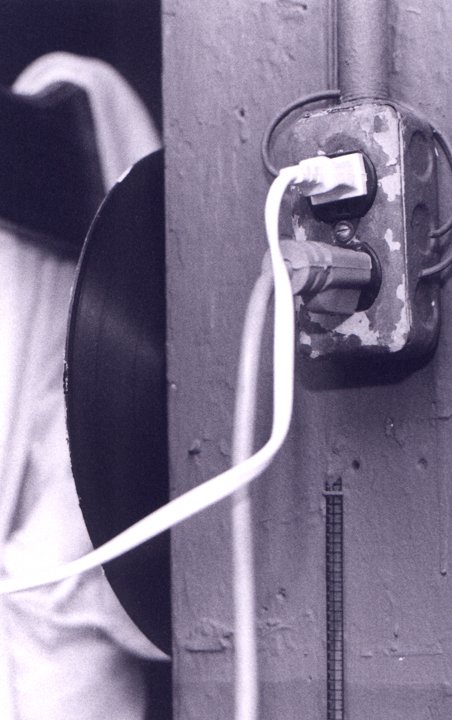

On the upside, the rent was goofy cheap, and, when you’re a fanatical young artist, the prospects of art production with the minimum oversight or interference from management can be appealing. If those “positives” meant putting up with the occasional Lord of the Flies moments, the odd disputes and logistics or maintenance problems, so be it. After participating in the build-out, I sub-leased a studio from Somers. I forget the exact dimensions. The mostly unfinished drywall did not reach the high ceiling. The breakers might blow at any minute, depending on what was plugged in the outlet. A film of ancient grit and dust covered the exposed surfaces. The paint was peeling off the walls and there were leaks and weird chemical smells. Noise pollution could be a problem, as could some of one’s “eccentric” neighbors. There were spiders (more on this later). And so on.

I made the best of it. On good days, I imagined I was living the artist’s dream! This would be my atelier for the next handful of years. Looking back, I can say that Chestnut was profoundly important in my artistic evolution. I accomplished an astonishing amount of often experimental work. In the many long hours spent in that very un-pretty factory building, I accumulated a tremendous body of experience, which has since proved invaluable. When Lain invited us to share Chestnut tales, visceral memories I had not tapped in ages cascaded into my consciousness. An artist studio can and should in certain instances be a solitary environment, and it turns out there is nothing necessarily romantic in that fact. Chestnut provided creative isolation in plenty.

It also could be a special, even unique site of exchange. For the first time in my art career, especially after Somers left for Santa Fe and I moved into his bigger space, the studio became the architecture for encounters, a hub, if you will, for conversations, performance, for teaching, and - most importantly - fostering relationships colored by the grunge atmosphere of Chestnut. Nirvana never sounded better or more authentic than it did blaring on my studio boom box in the wee hours. To remember Chestnut Square then for me is not much different from trying to recall a vivid dream, in its lurid, lugubrious details. Studio Time is not normal time. This scruffy studio eventually possessed its own charmed if not charming life, was animated by its own edgy vitality and spirit. I took this all very seriously. I was careful who I invited over - the roster was exclusive, if quirky. Over the course of months and years of use, mundane studio procedures took on the characteristics of offbeat alchemical ritual.

“Diana” [PJM; source photo 2000, digitally manipulated and output for “CONTENT” (2010)]

The Chestnut studio became a vehicle for vision, the manifestation of which required gritty physical mix of focused often sweaty labor interspersed with spells of Seeing, more than looking, of studious inspection and intense introspection. Art is a strange concoction. The studio can be likened to a laboratory, but my lab was neither clean nor controlled, as such. The world, nature can be an artist’s workshop, if you’re a plein air painter. Chestnut had its own artificial or plastic worldliness, which isn’t to imply it was an unnatural place. When you pulled into one of its unpaved parking lots, you could feel it looming. I loved it. Chestnut then always had a touch of broken-windows danger to it, the threat of fire or collapse. Or being mugged. You had to have your wits about you.

Today, because of computing, the idea of artistic production has all the same features of doing a spread sheet or playing in an app. For reference, see the MIT MakerWorkshop, a model much-emulated through STEAM-inflected academia. Common contemporary modalities allow for an artist to delegate production to men and machines on the other side of the planet. That was not my Chestnut experience. In the space that I eventually called Art for Humans Studio #1, a real 4D drama did unfold. Although visitors and voyeurs passed through it, I was the primary witness, viewer, audience. Chip Cox and Dane Carder briefly shared the space with me. Collaborators, such as Charlotte Avant played special roles along the way. But in the end, in hindsight, my Chestnut experience was uniquely my own. Twenty-five years later, having occupied a fair number of studios all over, and having in a variety of capacities visited many artist studios of great variety, my qualified or side-eyed fondness for that long-gone place and time remains.

Dog Show #11 (Photo by Trey Mitchell, 2001)

6

If memory serves, my most recent visit to Nashville was on the occasion of a solo exhibit at David Lusk Gallery in 2014. The development in the WeHo area that includes Chestnut IWedgewood-Houston-Chestnut Hill) over the past two decades has displaced my chronicle and recollections of the Chestnut Experience. It’s such an American storyline. All the sudden, your city was gone. This is not your beautiful house. This is not your beautiful wife. The totality of such post-contemporary phenomena, foreseen by Pretenders and Talking Heads, is breathtaking. The phenomenon evades recursion, because the reductive approach when applied to this subject becomes clogged with absurdly incompatible explanations and inconsistent perceptual frames. I believe it’s meant to. Fashioning any post-modern theory-addled gobbledygook into an explicatory blurb (“The synecdoche and metonymy together comprise the simulacra as existence”) is patently insufficient for obtaining meaning out of the thing. Meaning is an afterthought in capital redevelopment projects.

Strictly materialist rationalizations and justifications carry the gravitas, inertia and momentum of essentialist utilitarianism. Which is to say, they ignore inconvenient. collateral impacts, by necessity and convention. The confluence of narratives only becomes weirder as the particulars are parsed. The Chestnut Experience I recounted warrants not even a footnote in the promotional accounts being promulgated by the plethora of interests now invested in Wedgewood Village. For me, it’s hard to merge the realities of now and then. It’s a challenge to not relegate our lived Chestnut drama to immateriality, the spectral realm of a ghost story. The virtual representations of the development, coupled with the press and marketing info attached to the operation, only disorient me further. I catch glimpses of the old Chestnut, but they cannot fuse with either the past or present.

∞

Made at Chestnut: “Refugee,” charcoal, stencil, Golden acrylic quinacridone red-gold on wood for “War” series, 2002

Having lived in cities like NYC and LA, of course I am familiar with the phenomenon of historical displacement. But the basic features are the same when considering how my home town of Beckley, West Virginia has changed, since I moved away in 1982. More or less the same drift holds for every station stop along the route of my life. It is a common one in America over the past several decades. Whether you identify it as “Creative Destruction” or gentrification, however you contextualize it, one of the symptoms of the phenomenon is the evaporation of shared memory, of social cohesion attaching to architectural longevity or sustainability. The malaise is borne of the lack of continuity in the configuration or composition of place and people in the temporal topology. We have, consequently, a real crisis of belonging brought on my the continual loss of recognizable landmarks in our constructed realities.

In the post-contemporary, more and more, the phenomenon is a function of policy, dogma, and redistributive economics. The wholesale retooling of the country’s imagination as it applies to urban design theory for quality of life and work has manifested in projects just like Wedgewood Village in Seattle, Austin, Atlanta, Boston, Phoenix, Minneapolis, Chicago, Denver, etc. The Big Tech players (Amazon, Google, Apple, Microsoft, META) have played an oversized role in the idealization of this programmatic or schematic reconstruction. Big Finance (Blackstone, Blackrock, et al.) have capitalized on conditions created by The Great Recession, exacerbated by mass migrations from the coastal states during the Pandemic, but also due to a blob of other contributing factors.

Competing visions of the future and nostalgia for the past can be either explicit or implicit in these rapid-redevelopment schemes. Wedgewood Village is a middle step toward the Smart City model. This trajectory suggests the accelerated abandonment of an of American Lifestyle that is rooted in the interwoven mythologies of our iconic small towns, distinctive regional cities, and the bi-coastal metropolises, connected by planes, trains and automobiles, mail, phones and other lines of communication, old and new. The Highway is a key element of that construct. Think of how much this confabulation informs our culture and arts, in its totality heralded as the American Dream. The WeHo district is what Bruce Sterling identified as “Design Fiction.” As such, it creates a believable simulation that mashes up concepts (i.e., history, aesthetics, ideology) and desire to output a tech-dependent product that subtly communicates nostalgia and futurism simultaneously. The elements of natural, worldly risk are mitigated, as per corporate maxims. The whole operation is thoroughly, prominently managed and branded.

It all smacks of Baudrillard being right, and Heidegger, too on the problems latent in the post-War advances of technology. When one begins to critically analyze the scenario, odd associations turn the exercise into an encounter with hyperreality. What materializes, from that angle, is an uneasy realization that Disneyland’s Main Street, USA is a conceptual precursor of Wedgewood Village and similar developments. One can extrapolate from this insight, that a conversion program permeates post-contemporary existence. Consider the banal menu of CGI-heavy Hollywood comic book-based blockbusters. Or any other consumption-driven markets, dependent on our shared cultural experience of now-vacant myths. Also consider, how those imaginary constructs are being systematically displaced and replaced. How can the wave of reactionary sentiment be surprising, given the ubiquity of these weirdly schismatic distortions of conservative imagination?

What I find most interesting in all this is how art and artist appear and disappear as the phenomenon progresses. Naturally, because I’m an artist, this facet sticks out in my mind, but I get that the situation is kaleidoscopic. Due to the post-contemporary nature of the phenomenon, someone else might be drawn to an entirely different thread, as interesting and pertinent to them as mine is to me. For instance, within the constraints of our subject — the phenomenological Chestnut Experience — a Jewish person might be more curious about the history of the May Hosiery Mills due to the owners’ immigrant story and role in saving German Jews from the Holocaust. They might contextualize the story/phenomenon differently, linking the Zionist May family history to what is happening now in Israel and Gaza. Post-contemporary reality is multi-faceted and -dimensional. We can approach it from all angles, but we’re not looking at it from the outside, in. In truth, it’s the opposite way round.

Proposal video for the Frist Center CAP inaugural. The exhibit concept segment shot at Chestnut begins at 2:40.

7

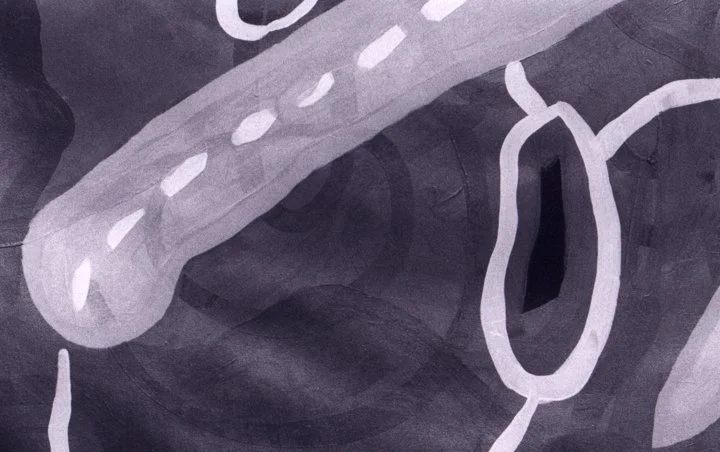

The painting I am submitting to exhibit in “The Key Show” is a visual representation of the phenomenon outlined above. It is titled “N-substantiation,” from the “Currents, Flow and Reproduction” series of The VyNIL Cycle.” A post-contemporary (4D) painting is not about anything, as such, in the way art following the concept-to-object modality would be. “N-substantiation” is not the manifestation of an idea, although theory and thought evoke its basis IRL. Art has its own authenticity, autonomous from discourse, nominal and numerical systems.

In the Post-digital or post-internet phase, it is facile to overlay the linguistics of machines and networks on art. Art is also resistant to theoretical or critical contentions (e.g., contingency, especially as per Derrida and Jean Luc Nancy) rooted in Continental, ‘68er post-revolutionary thinking. “N-substantiation” is art, not content, image, in-context, and so on), nor is it its own negation. The painting is a fact on its own, incontrovertibly real. The language and all interpretation of it is a derivative of its actuality, its being, in and of itself, to refer to the ancient Kantian framing. It owes its real-ness as much to physics, chemistry, optics - I.e., science - as it does to words and disciplines like psychology, sociology and anthropology - I.e., the modern and contemporary humanities, including modern/contemporary history.

With respect to artistic intention — which according to certain schools of psychological and sociological ideology is problematic, if not impossible — one of my central motivations in creating “N-substantiation” and the bodies of work to which it belongs is to make a beautiful painting, within an evolving series of paintings. I intended its colors to be lovely, its composition to be harmonious, to show mindfulness and care. In the VyNIL Cycle I am expressly concerned about the technique applied. These artworks are not technically perfect, in my estimation, but they do evidence artistic proficiency, in the traditional sense. They do not cleave to Classical precepts of the Ideal. They progress along evolutionary lines, as quasi-autonomous objective events, reflective of time and place, and inextricably link to their maker, myself.

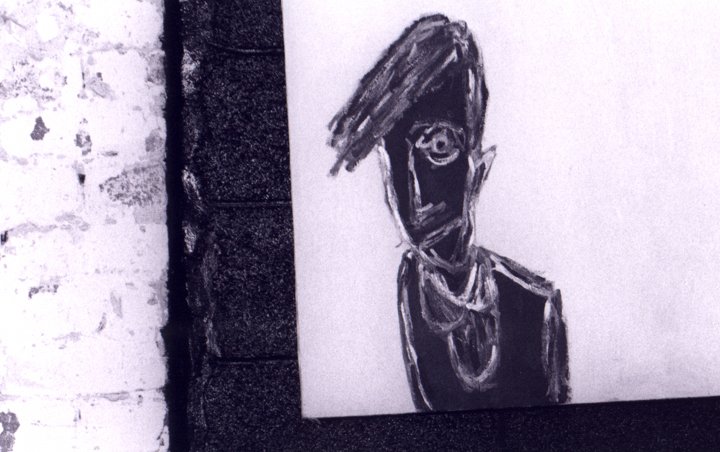

Made at Chestnut: “Blew My Mind Guy” - acrylic and ink on paper, 2001

“N-substantiation” is situated within the progressive movement of Western painting, and in my mind, this is not an assertion that automatically demands or affords dispute or repudiation. Especially not of the sort that is typical of the recent art world swing (e.g., see 2024 Venice Biennale, “Foreigners Everywhere”) toward Identity and Inclusivity being the prime drivers of aesthetic credibility. My artwork abjures the re-definition of art in the service of political and social reformation, on the basis of race, gender, geographical redistribution or recognition, among a host of externalities current en vogue. My painting, as an art object, has absolutely nothing to do with any of that, which is intentional, but also a function of my focal art experience/education(s). Which does not mean I am against any other artist or art claim. Which is to say, my art is not reactionary. The exact opposite is true, because I am a democratic art practitioner. Ultimately, as much I love the melting pot, I am for my own art, and all its roots.

My contention is that “N-substantiation” is as a post-contemporary art object phenomenologically representative of the lightly contextualized/-izing Chestnut Experience put forth above, and by extension, the concordant stacked phenomena noted throughout this essay. That statement prima facie might strike the casual reader and viewer as convoluted, complex and confusing, and understandably so. To get the drift of the declaration, they (the reader/viewer) would not only need to possess a fairly thorough familiarity with the arc of my art, thinking and writing to relate “N-substantiation” with the 4D sketch of “The Chestnut Experience” and the phenomena it explores; they would need to possess a broad foundation in the various domains and field perspectives layered into the study. On my side, that is a lot of expectation to foist on a viewer or reader, which is why I don’t worry about it much anymore. Further, it explains to a degree why I choose to create paintings now that are visceral, appealing, and inclined to surface beauty, work not dependent on the viewer’s visual or theoretical literacy.

Not that long ago, on the other hand, I felt passionate in my advocacy for educating as a means to end, or at least resist,f art de-definition and thematic dissipation. I committed to a wide-ranging practicum for improving dimensional art analytics, for my own edification, then for informing others, via media and networks. These days, I am more inversely or internally practical, and wizened. The journey has been long and twisty. So, for example, I may realize what Don Judd was getting at when he argued that New York was more concerned about real estate than art, because I researched his life, art and thinking at depth, during my MFA studies in 00s at CGU. And I also understand what motivated Judd to relocate from NYC/Spring Street to Marfa, TX. I can further appreciate, as a result of the investing in Juddian studies, how one of America’s great art destinations was founded. I wouldn’t like the reader to regard my artsy disposition these days as jaded, tarnished or gnarly, but it’s okay either way. I came by it legitimately. Ultimately, the proof is in the art itself, which does not lie. As for the relationship between “N-substation” and the sketchy Chestnut Experience: they share at root the same elliptical logic. In this framework, action is more a determinate than the idea of art. It is a post-Pollock perspective, not argumentation.

This video really gives a sense of the interdisciplinary activity we were generating at the time. Chestnut was very much a nexus for the action.

8

In 2019 and -20 I penned a three-part response to Daniel Buren’s seminal 1979 essay “The Function of the Studio.” Buren is the accomplished contemporary artist who has for decades used stripes (and other design tactics) to affect a great range of substrates and surfaces. My three-part series is titled “The New Studio” (see Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) and contains a thorough analysis of Buren’s theory and practice, which in turn serves as point of origin for an in-depth dimensionist interrogation of the artist studio, its evolution and status quo. My study covers much ground, approaching the subject from multiple angles, and I recommend the texts to flesh out some of the speculative research and views I bring up in “The Chestnut Experience.” “The New Studio” concludes with a meditation on hyperrealistic or Meta- features of the Atelier Brancusi display at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, in the context of Buren’s assertions about Brancusi and his studio.

In subsequent illustrated texts I extend the investigation to cover post-contemporary art production phenomena like Meow Wolf, and some of our artsy interventions from Occupy Wall Street, among other related topics. The artist studio is worthy of its own field of art historical study, encompassing a rich and diverse structural set comprised of forms and practices and the ideologies that bind them, all of which has been disrupted by the new technologies (e.g., prompt-based AI image generators, which I wrote about recently HERE). Today the definitions of art and artist and their role in society are as a result almost completely fungible, although this assessment applies variably among art world hierarchies [This observation is ironic, given the meteoric rise and crash of NFT “art” - PJM]. One can as I have track lineages from Michelangelo through Warhol to illustrate types of studio-based art production, and provide prodigious examples of variants over centuries through the present.

Few artists today occupy a single studio throughout their careers. Most migrate from space to space, according to their needs and means. Some artists have never worked in a dedicated studio space, toiling in corners of their home. Others only experience the studio as part of an academic curriculum. It is more likely today that a self-defined artist considers a computer or mobile media device, a tablet or smart phone, to be their “studio.” This trend is massively encouraged by the makers of hardware and software for creative applications. Social media has added to the complexity and confusion infusing the post-contemporary idea of an artist studio. To see what I mean, check out Devon Rodriquez, and his 2023 dust-up with Artnet News editor and important writer on art and technology Ben Davis.

Made at Chestnut: “Vision,” assemblage from found and printed materials, tape (PJM circa 2000)

In his rise to fame, Rodriquez shared videos on Tik Tok of himself sketching portraits of subway passengers, to whom he would give the completed sketch. Rodriquez through his preferred Web 2.0 platforms and channels attracted an enormous following, and built a lucrative art and media business career in the process. Where, exactly, would one locate Devon Rodriquez’s “studio?” Is it the A Train, or the commercial production-quality set where he was filmed sketching a portrait with spicy hot Cheetos dust for a viral video? To this example I would add another important post-contemporary art phenom, Angelicism01. The “art” is itself multivalent and dimensional, which terms also are appropriate for Angelecism01 the “artist” - which in fact is a credit-sharing fluid collective, cleverly distributing their non-definite or -conclusive cinema as projections in a selective or curated sequence of events in venerable showcase theaters. This serialized revelation of their extinction art is generating a radical discourse through multiple cultural media channels and generating significant attention in the circles whose pre-occupation is pop-cult currency and attraction, among the masses of followers. For Baudrillard and others, the domain of seduction.

Detailing the components coming together in Angelicism01 is not necessary here. The takeaway is that this marginal art world phenom is highly decentralized but capable of congealing into art-newsworthy action, within very traditional frameworks, using very non-traditional or new media tools and applications (e.g., Tik Tok, samples, memes, ephemera, etc.). Again, in Angelicism01 we have a really fascinating and compelling artistic and/or creative enterprise, timely and relevant, which exists outside the previous conceptions of artistic production. Here I would make a gesture to loop the subject of Buren and Angelicism01, by pointing out that both proclaim extinction as the urgent core of their post-revolutionary interventions. The connotations of “Extinction” for art and artists have changed radically over that time span, between the 1970s and today.

Projection video for "Heartless01" (2001); the section of video shot at Chestnut begins at 9:43.

9

A recounting of the Chestnut Experience (located in the middle of the extinction timeline above) must include more than the dimensional analysis or its phenomenology. The reader would be short-changed, if this essay were only that. This holds too for a dry chronology couched in the language of utility and economics, in the age of extinction. The historicity of the Chestnut Experience, as preserved and forwarded through syndicated monopoly media for ready dissemination (see Seth Price’s “Dispersion), is rooted in an ideology that pretentiously stipulates that meaning and value are only manifest within the context of capitalist narratives —for examples, Manifest Destiny and the underpinning notion of the march of Progress, i.e., the logos for conquest and civilization of the wilderness, savages, ignorance, and so forth, framed as inevitability. The materialism of development of real estate over time requires a very narrow limiting of views on what and who are essential, and in turn, that which (and those who) in both information and actuality will be made invisible. The ontology of the players and agents is subsumed by and in the game of ownership and acquisition, which operates more like a regime for monetization through thematic and systematic extraction and exploitation. Violence as a key feature of the process has lost its overtness, which is by design. At certain times, it reappears, when dissent and resistance against Command provoke a reaction from power actors (e.g., OWS, Standing Rock, Cop City, or the pro-Palestine/anti-genocide peace protests).

Made at Chestnut: “In God’s Hands,” acrylic and ink, for the DddD exhibit “In Sickness & Health” at In the Gallery (2000)

In “The New Studio” I shared images, moving and still, of my studio-based artist life. The subtitle for the concluding section of the text reads. “The Studio Is a Function of the Artist.” This provocation flips the modern and contemporary script in favor of the studio models possible in the post-contemporary, and to some extent the post-internet/-digital modes of production. If my framing the phenomenon in art-speak blurs the simplicity of the triangular form of the phenomenon’s essence as lived event within a dimensional formal, symbolic and/or structural framework, I would argue that problem is due to the confusion of technical and epistemological in the definitions of art and artist. The problem is compounded by the traditional hierarchical overvaluing of ideas/text over creative craftsmanship in fine art (episteme versus techne, to use the Greek terminology). Beyond the discursive is the specificity of not only the art, but the artist as well, both of which can be argued to demonstrate the qualities of an Event - a happening in real time/place - on or within the human continuum, as such, both in being and productive of becoming.

The pictures illustrating “The New Studio” reveal the facet of the art life that probably is its most attractive feature for casuals and practitioners alike: the peculiar vibrancy of the life dedicated to art. The quasi-mystical art life so far has been pretty close to impossible to adequately represent in film, fiction, dance or music or any other medium, digital, analog, performative, or time-based. The artist life as such from what I can tell is untranslatable, and not only in the world of words, but also in the realm of all sensual expression. Poetry and poet share certain of the same characteristics, and Heidegger in his thinking on the Thing, Giving and Technology, surmised poetry would surpass art as a vehicle for cultural transmission. But from my artist perspective, absent the image, poiesis remains at an expressive disadvantage. The two disciplines (art and poetry) orbit the expressive world as sun and moon, with all due respect to the potency of the latter. Paul Valery in his 1928(!) essay “The Conquest of Ubiquity,” quoted by Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, predicted music (delivered to the home, as it turned out, by Spotify and Apple Music) would top the hierarchy, and there are merits to his case, if only quantitative, as in volume/users. Again, these conjectures obviate the art object as the sui generis Thing. I think this makes their arguments partial non-starters. The reason has something to do with the peculiar mesh intertwining art and life, finite and infinite, which is to say relative to Time, that constitutes a generative form both material and immaterial. The energy that fuels art is perhaps the same or close to the reproductive energetic that drives and sustains our will to survive, and also makes babies.

At the easel at Chestnut, working on the “War” series, circa 2002

∞

The art studio historically can manifest as a multi-use facility. Throughout the 20th and early 21st Centuries, “studio practice” has come to mean nearly anything. Compare at the art world apex the art labor plants of Anselm Kiefer, Ryan Trecartin and Beeple (a/k/a Mike Winklemann). Or Marina Abromovic (an institute), Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst. Or Urs Fischer, Ai Weiwei or Yayoi Kusama. Then, check out Hyperallergic’s longstanding series, “A View from the Easel,” which features studio photos and artist responses to a handful of conversational prompts. Over the course of hundreds of posts, Hyperallergic has accumulated enough documentation to platform a robust discourse about studio conventions and utility, a practicum for art production. Is it trite to say Artist studios are like snowflakes?

That assessment provides an adequate context for moving our focus to Chestnut and pondering what was most unique about it, in its transitional period between manufacturing facility and Creative Class development. The most special thing about the Chestnut Experience from my perspective is what I and we made of the opportunity afforded us during Chestnut’s years of decline and neglect and subsequent restoration and conversion into its current iteration. Some of us made art, yes, but all of us made memories out of relationships that were and remain central to our life stories, individually and collectively. I admit to a certain humanistic bias, but I will contend that it was us artists who kept Chestnut “alive” long enough for it to be recognized again for its makeover potential. It’s a common enough pattern. Artists take over raw or neglected buildings, neighborhoods or districts, followed by the developers, the bars, restaurants and hotels, and then the Yuppies move in. Bye bye art scene!

If one considers the root of studio, one realizes the studio is a codified architectural locus for study. What is the subject of study for an art studio, if not art? It turns out that the subject of art is in practice the study of life, as much as it is the study of technique, art history or the theory of art’s role in society. Because of art’s nature, the project within the bounds of the art studio is the making of things out of life, from the stuff of life. In a working studio, the progression is productive of the exhibition, the means by which the artwork, the thing of art, is reintroduced to the world, as an object whose subject is some aspect of life itself. In this model art is processed and performed in the art studio by the artist, with a two-way- or reciprocal-through-put binding art directly to life. The output, the object, is subsequently re-invested/-inserted into the lifestream as such via public exhibition. It all happens in the spirit and format of a gift exchange, even if money changes hands down the line, as the formal exchange take on the complicated characteristics of external economy. This procedural description is elliptical, and somewhat recursive, but it gets at the distinguishing quality of that which instills art and artist with value and meaning, outside and preceding the economics of means and value, what makes us essential in any healthy community, which is more than its economics. Artists always are Outsiders in the Capitalist society, where art gifts and their administration are dictated by the philanthropic class (e.g., Eli and Edythe Broad), who just buy things. They don’t make art, they use it.

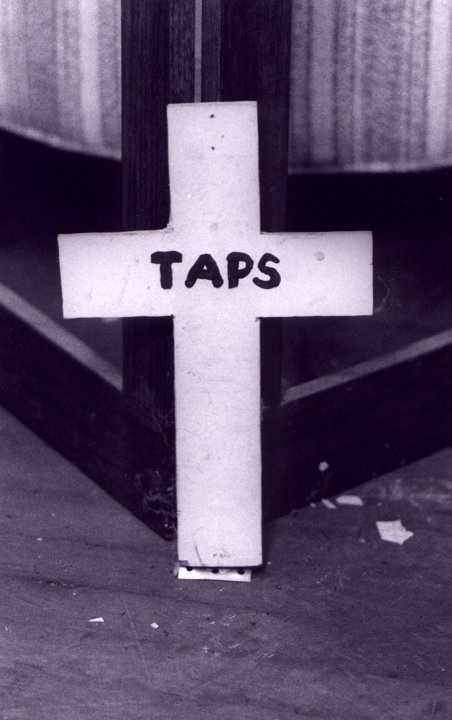

VAAN Open Studio Tour flyer, circa 2001 or -2 (PJM)

10

The bittersweet subtext to the actuality of the May-to-Chestnut-to-WeHo narrative is a conjecture. It is a What-If scenario. What if we lived in a parallel dimension, in which society prioritized art over Return on Investment (ROI)? What if Nashville was run less like a business in that alternate reality, and the city was governed with different priorities? What if our economic model was aligned with gift exchange, instead of the one that more or less determined the outcomes we witnessed over the past century, playing out on that particular parcel of land? To entertain the speculation, our reverie would necessitate society having a different schema for the distributions of wealth, property and labor. That alternate society - let’s call it “N-10city” - might be modeled after, say, the precepts outlined by Thomas Paine in “Agrarian Justice.”

The apportionments in the configuration would generate a different, better outcome. Maybe? All of which to say, “Another World Is Possible.”

Artists are dismissed as dreamers by the so-called pragmatists among us, who are generally found to be heavily invested in the status quo and the prime beneficiaries thereof. Our futures however are a function of our imagination. Art as a discipline is a means by which the imagination is oriented to achievable results, as a practical matter. Rather than ignore the directional suggestions from community-centric artists, who look back while looking ahead, society might be better served by giving a seat to them/us at the civic planning conference table. I’ve sat at that table a few times, and we artists belong. It would probably help if artists unionized, the prospect of which is akin to herding cats. I know. I’ve tried! When it happens, the artist’s inclusion in governance inevitably shakes things up. We Americans have precedents for such a model in the WPA Arts in Action programs of the New Deal. Fruits of these programs are still visible today, throughout Tennessee almost 100 years after the fact.

Made at Chestnut:” Signal Flag #57” for SEAM01 at TAG (The Attic Gallery), PJM 2001; layered digital adhesive vinyl and banner print

One can see few signs that an alternate vision for art and artist is likely anytime soon. More likely is proto-fascism, oligarchy and autocracy, nationalist theocracy or some combination thereof, a state which some days seems to have already arrived.. These sorts of power structures produce certain kinds of art (portraits of royalty, propaganda, and so on). We were conjuring speculative alternatives. I wonder, What if Bernie Sanders had been elected President in 2016 and/or -20? Sanders’ inclination to reintroduce the policies of FDR in the 21st Century for Americans might have manifested a revival of the post-Depression, pre-WWII public art programs. Such a revival might have entailed the redistribution of art power from top to bottom through some achievable adjustments in cultural policy in the United States. Let’s talk about it! That discourse has been fundamental to my practice for decades, and carried forth through radio shows, publications, via the web, etc. My Masters in Arts Management from the Drucker School adds a qualifying credential to my CV, and I’m proud of it and the work put in there. Through that program I met a lot of impressive people on the admin side of the art world, and was afforded access to LA’s non-profit art and culture scene I wouldn’t have otherwise had access to. But the preponderance of my ideas and opinions on the subject of the role of art in society are born from “real-world experience” gained over the course of a career in the arts, shaped by a lot of research, conversations with authorities on the subject, and more.

In 2009 I was one of nine working artists who participated in the first (and as far I know only) online forum on the NEA and public arts policy in America, hosted by WESTAF and encouraged for by the freshly minted Obama administration. I argued then for the establishment of a next-generation version of public art/WPA-style programming. It became obvious in short order who would create headwinds for a 21st Century New Arts in Action movement. The opposition arose from the consumer portable art industrial complex. Massive corporations like SONY and Disney were consolidating cultural power in the 00s through a dimensional strategy branded so as to displace “Art” with “Play,” “Creativity” and “Innovation” as keywords. The top tier art world, its collectors, the major institutions, auction houses, fairs biennials and retailers, the art intellectual/academic professionals dependent on these entities - none had any interest in the success of a logical, democratic, bottom-to-top reformation of the domains for arts and culture. Which is still true today. To be honest, They won the culture war over art, and we all are losing art as a consequence.

What are we losing, exactly? One can put it in abstract terms, using words like “opportunity” and loaded phrases like “freedom of expression.” One can delve into the literature (e.g., Gregory Sholette’s important 2010 book Dark Matter) or follow current analysts like the aforementioned Ben Davis, or track the excellent threads of New Models, Brad Troemel and Joshua Citarella, and so on. These sources illuminate the major issues in play now and introduce you to people who are organizing towards alternatives that might prove sustainable and more democratic than those that have dominated the field and (still) dominate today. One of the most promising speculations these alt.art folks entertain is the possibility of alternative platforms and currencies, although we should keep in mind there are immensely powerful forces behind parallel developments, most notably in AI, but also in correlating arenas (e.g., METAverse/VR). Bootstrap or DIY artist-driven projects probably don’t stand a chance against these behemoths.

Joe Sorci in his Chestnut Studio, circa 2000 (PJM, for Joe’s Destination Gallery exhibition)

11

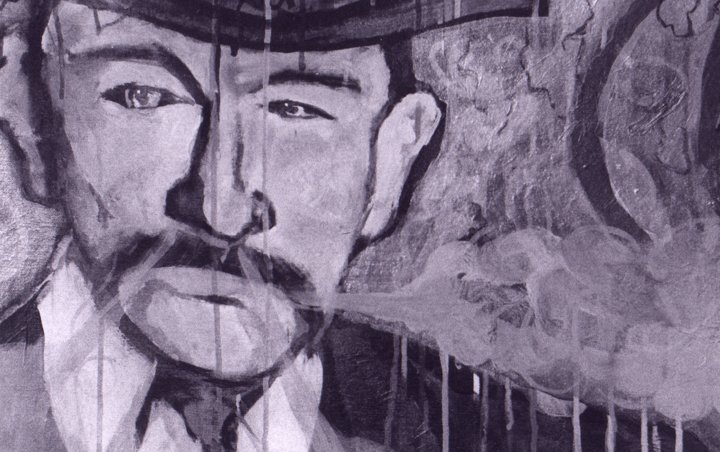

I spent hundreds, maybe thousands of hours in my Chestnut studio. Primarily, I used it as a painting studio, but I also executed many drawings, sketches and studies there, using various media (pencil, pastel, charcoal, ink and so on). The collectives for which I served as Lead or co-Lead Artist, DddD and 01, sometimes met there, in whole or part. I taught private art lessons in the space, usually allowing students to use my materials. Visitors dropped in throughout the day and night, sometimes by appointment, sometimes on a whim. The building was locked outside of business hours, so logistical arrangements might be necessary. It wasn’t unusual for other Chestnut denizens to stop by during a break, to borrow a tool, or to have a coffee, smoke or chat. The stereo played radio and CDs. The lighting consisted of the infernal fluorescents and an array of clip lights, supplemented by colored lights and a pair of black lights.

The trains rolled by at regular intervals, always blowing their horns as they passed. They provided atmosphere. At night the building mostly cleared out. I often scheduled my day so that the evening hours were dedicated to extended painting sessions. It wasn’t unusual for me to work into the early hours of morning, sometimes until sunrise, depending on production deadlines, or because I needed to complete a painting layer or finish a work and didn’t want to interrupt the flow. Over time, I settled on a playlist or soundtrack for the studio. After midnight I often listened to Art Bell, which could get spooky. Radiohead was a mainstay, but my CD collection contained about fifty CDs. The rotation would change, but was consistent over time. A tune for all occasions.

DddD, circa 2000

When I would get tired or zone out, I had a heavy bag I would work over. During breaks, I would check messages and do call-backs, depending on the time of day or night. I sometimes wandered the halls to see who else was around, after washing brushes in the hallway slop sink or using the bathroom. The one closest to my studio was always disgusting. Although I had heard rumors the building was haunted, I never saw a ghost. One did hear the odd, unidentifiable sound occasionally. Chestnut then had the the vibe of a real-life movie set, although I’m not sure for what kind of film. By 2000, I had begun to explore photography, animation and moving image in earnest, in conjunction with computer-based processes. I purchased several video cameras and still cameras, digital and film. The studio (and by extension, Chestnut Square) became a backdrop for a series of shoots and media projects.

Collaborations happening through the DddD/01/AFH collectives with filmmakers, videographers, photographers, as well as interactions with post-production facilities like Ground Zero and Chromatics, changed the way I thought of the studio and studio production. Working with models, actors, dancers, musicians and an assortment of talented characters, inspired me to pursue modes of expression on the broad spectrum of arts and science. In a given day then, the studio could host a painting or drawing session, a photo shoot, a production meeting, an art class and a hang-out. Man! One never knew what might happen from day-to-day, or week-to-week. It was awesome while it lasted. Unfortunately, for all kinds of reasons, the run eventually came to a close. Sometime in 2002 or -3 I made the decision to close down my Chestnut operation. Part of the calculus — my parents were in bad health; so I left Nashville and returned to West Virginia to help take care of them.

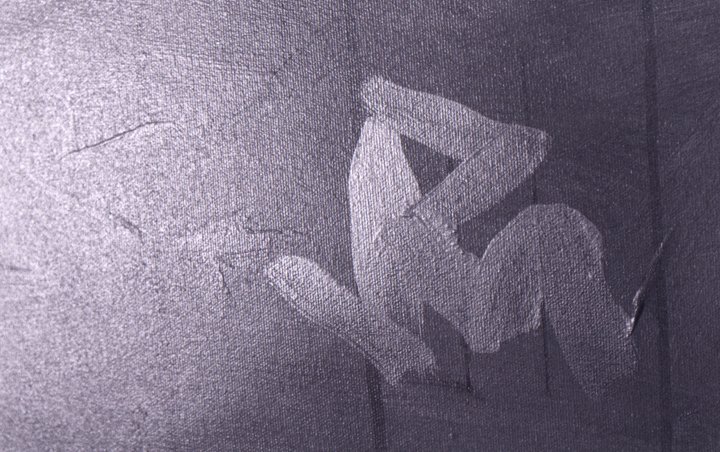

Made at Chestnut: “Effigy,” acrylic on wood, for “Where My Feet Stick to the Ground” at Peanut Gallery (1997)

I recognize in hindsight how fragile, how precarious the Chestnut Experience was. I have no illusions about it. There were many, many beautiful moments. There were also the brown recluses who infested the studio for a year or two. I got bit many times, over fifty by my count. I accidentally set up an optimum grow environment for the critters, by leaving the lights on 24-7 and not installing an air-conditioner/climate control. Until Chip picked one up one summer, and I started turning off the overheads when exiting the studio, the arachnid plague was dreadful. The post-industrial art studio has its romantic aspects, but it’s not a place for the timid of heart. It takes a certain type of person. An OG studio artist must withstand the solitary nature of the work, or at least be comfortable within those parameters. The studio as multi-use-facility is another beast altogether.

To manage that sort of hybrid operation, one must have the skills and mindset of an executive producer, or a circus ringleader. To toggle between the two modalities requires a schizo personality. I don’t mean to suggest the collective/studio or multidisciplinary artist is mentally ill. But there is definitely a schism between the two programs or processes (solo/collaborative or group). Which is why a space like the one I occupied at Chestnut was so invaluable, and productive. It was big enough to compartmentalize, in both the actual and metaphysical sense. But without the community of people who animated it over time, that studio would have been nothing more than a decaying vestige of a bygone era, the epitome of industrial waste. And what animated the people who animated the space, myself most certainly included? The shortest, best answer is the love of art and life.

Photo: Rebecca Walk (1998)