January 7, 2014

By Paul McLean

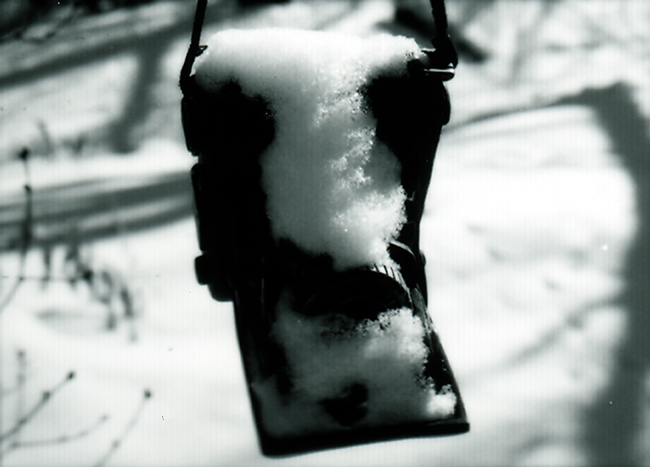

I’ve been watching movies for a few months, since October, when I finished the residency upstate. Through part of November, December and now freezing January, once Good Faith Space was shuttered, and another viable collective New York City effort met with a minor note conclusion, or at least the appearance of one, I used websites that exist outside the corporate intellectual property regime to catch up on the latest cinematic offerings from across the globe, and to review a good sample of old features, too, some I had watched before, others for the first time. To put this undertaking in a maker context, for the first time in many years, I have for the most part done without the camera, both the moving image kind and the still camera (I realize the two exist as one, now). The impetus for, at least for a while, abandoning the camera, was twofold. Hate to sound "precarious," but I needed cash to travel to Switzerland and the European Graduate School in the summer of 2011, so I sold a fairly new Canon Rebel and two camcorders. I suppose I knew better. Over the course of my career, I’ve learned the lesson, familiar to those in the arts who rely on tools and gear to practice their crafts, that selling off your shop tools is an action to be avoided, if at all possible. It’s almost always harder to recover one’s gear, than it is to pawn it. I've rarely had to do such a thing, and I probably wouldn’t have done it this time, but for an intuition that, for the purposes of re-orienting my vision to the primary experience of the world (universe), I should stop mediating the world (visible) through the camera lens. I am a painter, first. The camera frames experience, and as many thinkers on the subject have observed, that machine frames the visible or superficial world (perceived or received) in particular, maybe artificial, ways, which blur the distinguishing aspects of the Real and Illusion. It is a capture device, yielding derivative versions of what is. Also, the camera-derived image is one that connects to platforms for manipulating so-called “raw” material or data. Whether the picture is submitted to the processes of rendering in the darkroom or the digital editorial suites of software and hardware shops, the original undergoes a separation from itself through those processes, a dissolving of the contiguity adhering the image with what happens in real life, in real time. My interest in abandoning the camera as an artistic enterprise - at least temporarily - has to do with the feeling that diffusion of the actual moment in life is so important that any contrivance, mechanical or otherwise, diminishing one’s encounter with living and life, needs at certain points in one’s artistic arc to be minimized. At certain points, one musn’t shy from the world (unfolding) as it is at all, and for an artist particularly, or at least, for a painter, the camera is no replacement for looking directly at the world (action) in which one discovers oneself. By the way, this is not the first instance of my taking hiatus from the camera. The self-imposed camera-less sabbaticals have been periodic and sometimes extended for years, the longest phase lasting almost a decade, over the course of my artist life.

Call it an experiment in optic or perceptual management, and, with respect to the current one perhaps a dumb one, in its timing. Shortly after returning from my philosophy training intensive seminar in Saas-Fee in Summer 2011, Occupy Wall Street erupted in the financial district of Manhattan. I felt fairly idiotic for having no cameras then, given that OWS turned out to be possibly the best-documented political irruption photo-op in history. Cameras of all kinds were constantly evident throughout the movement. In fact, the camera, especially those contained in electronic mobile devices, characterized as “ubiquitous” in New Media discourse, found resurgent relevance via OWS in the arenas of political journalism. The democratization of photography turned a corner during Occupy, when low-res photos and videos, uploaded in nearly real time to global information networks, subverted the corporate media monopoly and undermined propaganda machines, whose agents had become arrogant about their capacities to shape and determine narratives of importance. There I was in the middle of it, with nothing but my own crappy Blackberry camera, the lens of which was a marred mess. After October 26, the occasion of my first visit to Zuccotti Park to attend an OWS Arts and Culture meeting, I became involved as a co-organizer of Occupennial, the ill-named offshoot of Arts and Culture that was to emerge as the Occupy with Art Working (and/or Affinity) Group not long later, a fluid membership collectively responsible for a number of significant OWS-arts-related undertakings. We generated a web nexus for Occupy arts online, and produced expositions such as Occupy Printed Matter, Yoko Ono’s Wish Tree at Zuccotti Park, Wall Street to Main Street, Low Lives: Occupy, CO-OP and more. My not possessing decent camera equipment for the year of Occupy, and the following one, which included the establishment of the Occupational Art School, proved to be frustrating on many levels. Of necessity, our efforts were DIY. Our often-momentous Occupy Arts endeavors were routinely, willfully ignored by forces within and outside the movement, and I was hamstrung at critical junctures by my inability to counteract measures meant to ascribe erasure to those (one sensed – Historic) efforts with the help of camera-enabled documentation. A lot of people and institutions were committed to us being made historically invisible, and all that attaches* to that condition.

On the other hand, due to the oppression of the surveillance state apparatus to which Occupy was constantly exposed (and which it did it great service, in its turn, to expose), a certain alt.value linked to our not ubiquitously recording the activities of OWS arts activists. Therein lies one of the crucibles of the new, let’s call it novadic, paradigm. Authenticity is inherent in unmediated experience. However, new possibilities for visual democracy are obviously expanded by the digital recording device wired to the Internet. OWS proved that. Just because the corporatized, militarized police state has infiltrated the network does not necessarily mean that “alternative” network media is not viable or valuable. In fact, the alternative is vital, because the alternative is really the natural phenomenon, which is clear when the alt.media is juxtaposed with corporate or state-controlled industrial media. However, this is not just a question for media philosophers and analysts to consider. As Occupy learned the hard way, civil liberties protecting one’s individual and collective rights to assemble, expression, privacy are susceptible to tyranny, and the means by which tyranny is enforced are a form of direct action, with very real consequences. OWS Arts and Culture, like OWS itself, was destroyed through interventions of the authorities and their collaborators (and/or dictators), over time. While it is true that the influence of Occupy continues to bear fruit, the reality is that the operational effectiveness of OWS was crushed by its enemies. Going back to the camera, fortunately, Occupy attracted many great photographers, intrepid video-cam operators and other supportive documentarians, so the erasure of the movement failed. Advocates came forth and continue to do so, in order to rebut the persistent campaigns to disappear OWS and its constellation of related effects.

Which brings me to another point, related to my disclosure about watching many movies over the past months, hundreds of them, serially: the immaterial qualities of the image, specifically the moving or cinematic image. One of the distinguishing characteristics of painting is the generation of the object-subject, the painting itself. A movie is relatively immaterial. A photograph exists somewhere in the interstices of those frameworks, the “plastic” and the immaterial. The digital field flattens all into its domain, with the “print” or projection being the output mode. Or, you can witness the “digital art” – whatever format - on a monitor. Comparing the experiential, perceptual scenarios for receiving art, as functions of medium, we can begin to develop recognition of limitations of each medium, relative to the appropriation methods on the user side. An aficionado of paintings must confront the painting in the museum, gallery, or on the wall of a home or some other type of edifice. Presentation for painting is a centuries-old craft tradition. Photography works within this same tradition, but also reaches into print, projection and monitor-based formats for exposition. Movies rely on the projector or monitor. The public (commons) and individuated means for encountering arts are fairly well proscribed, for now. Despite all the hype of “The New,” little beyond technical refinement applies to the construction for one’s encounter with the visual arts. The element of performance, which has been introduced as an expository element attaching to image, is really a superficial component, a superimposition, if you will. Performance is relevant only in 4Dimensional art, which fabricates interstitial context, connecting the image to a mediated environment to the rest of the world as a compound praxis. Absent the comprehension of parameters for the various artistic mediums (which is not exactly media), complex or dimensional art matrices are weak or worse, nothing more than situational parody.

We have a massive database of experiments in the domain, for evaluation. Peter Greenaway is as fine an example as any to use as a point of origination for dimensional analysis of related phenomena. We could also consider the big art fairs and biennials, which are really complex platforms, if utilitarian. We could look at Jay Z at Pace, or Gaga, herself. Probably the best case study of all in the new millennium is OWS, but the Bushwick Open Studio tours are very competitive, despite their general predisposition to the formulaic apolitical, which is to say, the uncurated or volunteer community collective. Unfortunately, since we live in era of cultural crisis, even a perpetual crisis or perpetrated everlasting crisis or managed sequence of crises, it isn’t realistic to divorce art from current events. We cannot pretend that art is plugging along on a separate track. Only a dimensional approach can suffice for representational or realist art, terms I’m applying here with 4D meaning, to encompass the endeavor of the artist, his role in the community, art’s purpose and quality as a progressive feature of and for art. I say this is unfortunate, because art could – and maybe should - be situated in its own channel, to use a New Media term, where it could and/or should evolve and progress naturally, positively without environment inhibitions. Alas, these are not our circumstances. Free art, freedom itself, is suffering perilous attacks as routine interventions, scaling toward utter devastation. Art in this aspect mirrors the human condition, is a symptom, as such, an indicator, which is its prime social utility and function. Several kinds of choice create art. Choice(s) is/are inherent in art. Choice is consequential to art, and art can inspire choice. This is why, when critics and others suggest that art does nothing, their critique is in actuality misconstrued.

For our list of 4D points of origination, to delve into the state of art today, we must also include Banksy’s residency in New York. In sum, the operations of Banksy and his crew exhibit advanced comprehension of the scope of available options, in mounting a production for contemporary art in context. Banksy’s “Better Out Than In” proved to be 2013’s most poignant project, revealing or mapping the major issues confronting any artist committed to working outside the property and management regimes, in the commons, as a democratic free agent. Kudos to you, Banksy, whoever you are, and your anonymous partners in crime!

Concurrent with my movie-watching regimen, I’ve been writing texts focused on property and free speech. As my thinking evolves in this direction, the endemic criminality of property regimes is as clarifying, as it is troubling. One wonders if it’s possible for art to “flip the switch,” to be a catalyst in the overturning of property-based tyranny. Conjectures are prone to facility. I realize that the owner regime may serve as a hedge against secondary or derivative mass behavioral problems, those that drive incomprehensible hatred fueling unimaginable violence, for instance. This is the syndicate’s argument in its defense, as the commanding or controlling force over the mob, justifying programs of extraction and exploitation, and episodic outbursts of brutality. This is also the way cowards justify inaction. Nonetheless, the venality of the banal presents a powerful problem to the reformer entrenched in a society that encourages the use of human shields by most offenders of a certain class or station.

It’s difficult not to conclude after watching Scorcese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, Woody Allen’s Blue Jasmine; or American Hustle, and then the very, even profoundly, more poignant – and notably less critically acclaimed - The Counselor and Out of the Furnace, that the dance-around full (psycho-systemic) disclosure in the movie machine, represented in each picture that arises out of that machine, as a conditional of industrial call and response mechanisms, has entered a macabre phase. It is as if the filmic auteur and his collaborators are coding confessional messages about their capacity for timely social awareness to their specific and general constituencies, transmitted through craft or product. Nothing new there, but the new code could be construed as confessional, or contemporaneous only, with the functions of both willful complicity and affected distancing abstraction demonstrable, woven or re-introduced or pre-introduced by editing or scripting, into the onscreen narrative as a vague, creative omniscience connected to action by some spy technique, like CCTV. What is that, Woody? A movie can situate characters in period costumes for dissociative purposes, and the script can maintain ambivalence on the moral question of art’s relation to the milieu, and the duration of the film can remind the audience that we are only participating in an entertainment, ultimately, and so on. Such skillful means can constitute an argument for internal veracity, but they can also belie plausibly deniable cowardice on the maker’s end to confront what’s happening now head-on. Still, film critics, that special caste, will dictate the parameters of artificial discomfort, as a service to the consumer portable entertainment industry. They launch cheap attacks on the modes of transmission, if not the content, as a method of avoidance of the proffered message, if they react reflexively, as hive-minders, to drama that runs contrary to “acceptable” precepts for Hollywood fare. They asserted almost uniformly that Cormac McCarthy speech translates poorly to the big screen, which is absurd on its face, compared to, say, page-bound storytelling in Blood Meridian. Christian Bale, they posit or infer, was better in American Psycho or Hustle. What if we create a multi-channel projection, featuring simultaneous screenings of a new movie like Her and movies like Bullitt, The Thief, The Getaway or Depardieu’s Cyrano de Bergerac? Nonesuch arrangements are out of the question, on the desktop. Try the experiment at home on your computer. Christian Marclay illustrated a related point with The Clock. A sequential selection or sample, grouped by theme and/or dictated by rules, situates the database in the role of collaborator, even producer. My reading of Benjamin’s “Author as Producer” suggests to me that our collective consciousness, if not praxis, must be expanded to include the archive of captured and created reproductions and its reformation, in a transthetic, dimensional format. As an aside, the problem with Marxian conjecture is its proximity to Protestantism. Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange torture/torturer-reformation sequence, a troubling commentary on the architecture of power distributed in the act of cinematic viewing, as perceptual inducer, hints (or screeches) at the Bernaysian underpinnings of the Metroplex. The begged question? Are we really complicit? I recommend McCullin. After all, we are at war.

[INSERT: Einstein on the Beach (au Theatre du Chatelet)]

[FINAL NOTATION (speaking of war, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the commencement of the “War on Poverty,” and the analysis {in Dana Milbank’s Washington Post column of the Republican Party’s “War on the War on Poverty”})]: Isn’t it clear, now, that a war on poverty, and the negation of it, which amounts in actuality – over time - to twin-pronged wars on the poor, should immediately be ceased? What is necessary is a war on the owner or property-regime, which could be meme-ified to read “A War on Being Rich.” I don’t know what propaganda films for that war, the one on "wealthiness," might look like. We certainly have complex precursors as cinematic visualizations from the 60s and 70s, such as The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Now, at least technically, we have more options for realizing a visionary film for promoting war on economic inequality. Considering for example The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, we obviously have a cinema grown more robust via an array of potent CGI tools. I know that art is often skewered for its corruption, although I would argue that the 1% art market is not really art, as such. Seriously, can anyone still argue that Metroplex movies are anything different? Is it even possible to conceive of cinema, except as a complicity, as an owner industry, a machine? Probably the technique, the mechanism, the system, is less central to a new revolutionary picture movement, than is the tool itself. What kind of camera one carries is the determinant. At least a still camera is yet useful for photographing paintings for the purposes of documentation. Come to think of it, the utility of the camera has, if one lives or travels through a place like Manhattan, come to mean the encompassing documentation of all movement, at least that's the totalitarian aspiration (TIA). The camera documents us from space, like the Eye of God. It peeps into our bedrooms. It flies through the air on the underbellies of drones, planes and choppers. It trudges through danger atop the helmets of our soldiers. Our rock stars [(LoL) like Justin Bieber], until they retire or OD, or start or re-start actor careers, while performing live, shoot us [in Justin's case, all Beliebers] from their platform, the stage - then immediately tweet/Facebook/Instagram them IRT. The bank camera catches us from multiple angles. The corner store does, too. And so on. Cinema, photography (commercial, fine art, amateur, whatever) – all camera arts contend with the fact of the all-directional lens. What is the subject now? Where does surface begin and end? Furthermore, the evidence of camera-readiness attends most every human gesture. How many of us go a lifetime without ever being photo-/video-documented? Now, maybe, we can revisit the 2006 animated feature, A Scanner Darkly, as the movie prescribes, “seven years later," and we can make an informed decision about its discomfiting verities. Truth, we might disclaim, is now in a state of imaginary, in no small part, because we see to believe, believe what we see, see what we want to believe, and trust none of it. Plato’s ideals and illusions have merged into an anonymous blockbuster production called The End of the World (Again and Again). The poet-rejecting philosopher deserves special mention in the credits, which will roll on and on, while no one watches.

> Check out: "Tesseract," by Percival Everett at BOMB Magazine; a worthy 4D creative writing effort.