AI Art in the Post-Contemporary Period [1]

A technical review of Craiyon with poiesthetic commentary

“Everything up in the air. A certainty of uncertainty. The only thing to do is to do. Not to be, only to do. To not be. Born to not. Nêtre, neverything.” -- Christof Migone, “NEVERYTHING” [2]

ABSTRACT

Like poisoned gum drops, seemingly harmless online AI graphic apps, now disrupting the digital graphics field, veil existential dangers inherent in the technology. Bedazzled and unsuspecting users play on. Advocates celebrate these widgets as a milestone in the visionary evolution of Machines, but, with Heidegger and Schirmacher looking over our shoulder, we discover layers of adverse concealment and compromise. Using the gimmicky Craiyon as a starting point, we track its context, subtext and affiliations. We consider contiguous risks for our becoming and being adjoining AI’s rise. Through illustration, we visualize how Craiyon’s lossy compression of “all-ness” and wonder subvert Philosophy and Art. Instead of orienting to beauty, AI art standardizes ugliness. Devoid of the multivalent givingness of Old Media, Craiyon administers abjection as art-flattening “fun.” Through artificial enmeshment, consumers of Craiyon, et al., drift further into moronic cyber-subjectivity. AI t2i* generators prove to be just another droplet in a tsunami of cynical net gadgets disappearing culture, effecting objective impermanence and erasure as a means of de-humanization.

*Text-to-image

“Neverything Post-Contemporary” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

KEYWORDS

AI, Craiyon, Philosophy, Art, Technology

“Continuum [4 Will(s)]” - mixed media on panel by Paul McLean 2022

ARTIST’S STATEMENT

Speaking freely. Some skillful digital art masters (for example, Patrick Lichty) and technical/theoretical practitioners and academics (e.g., Lev Manovich) have showed themselves once again to be keen and crafty early adopters of online AI text-to-image (t2i) generators, the latest digital implement. Nonetheless, overall, the tools and associated programmatic schemes do not meaningfully belong in the discourse on art, and their output is not art, strictly speaking. They do situate well in other conversatons and domains, however. The problem with orienting these gadgets to their proper locations in cultural, political, economic and technological discourses derives from their promotion immediately as art displacers or disruptors, on an x=x assumption that is fallacious. To illustrate this argument, I wrote a review of one of the AI t2i generators (Craiyon), and then produced a painting to confront the comparative approach of the mediums. The painting, a memorial to one of my cousins, among other things, is above; the essay follows. The key facts of the project include:

The painting and the AI t2i images do not exist in the same reality.

This is also true of the critical or theoretical commentary on both, as creative phenomena.

That both belong in a broad category of creative phenomena, or more specifically, artistic production, does not mean they are the same thing.

What arises from these statements? They infer a strict and limited definition of art, rooted in specific technical practice, ideology and tradition. Neither phenomenal thing obviates the other phenomenon. This determination extends to many other aesthetic questions, endemic of the post-contemporary period. That the position of distinction and difference is simple in its assertion points with respect to its value in originating a clarifying discourse for the aesthetic field, both material and immaterial. A subsequent analysis of commerciality and art, arising from this discursive and analytic origination, will reveal the schism between “art” and art-products or production, especially those designed for the industrial art trade and exchanges, including the ones most recently launched for NFTs. One hopes that a clarification of the question (what is an art object?) might provide necessary guidance to the next generation of artists and creative producers.

The generous idea that there is room for everything in art is not realistic, and is inherently destructive. The idea is certainly worth scrutiny, nonetheless. What at first blush seems a very democratizing concept (Everything Art), after even the most rudimentary domain survey, reveals the subtext of this all-inclusive ideology to be dark indeed. I get at this in the essay. AI is not a benign technology, and its intervention into the world of art is rooted in old models of uncompensated exploitation, geo-political, -economic and martial superiority, broad surveillance and so on. The deeper issues adhering to AI are philosophical, in that they belong in the exploration of human meaning and value, described in ancient occupations of Mind, Spirit and embodiment. In the post-contemporary period, these issues require our prompt attention and reviewing. Will any such systemic analysis propagate a social tech-reformation or -rebellion? Givens of history and currency suggest those prospects are dubious. There’s lots of money to be made. Still, who knows!?

It is my contention that a 1=1 comparison of art, using my own production as a case sample, and a small sample of my a2i-generated imagery (the result of a “collaboration” with Craiyon), with context does demonstrate effectively my own findings. Whether anyone else finds the propositions put forth below satisfactory is, auto-artistically irrelevant. The painting itself, upon completion, is autonomous on one level or dimension. - PJM

PART 1

“Not-portraits + Photo of Wolfgang” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

THE DANGEROUS ENFRAMING THING

“To what is the nonappearance of the thing as thing due? Is it simply that man has neglected to represent the thing as thing to himself? Man can neglect only what has already been assigned to him. Man can represent, no matter how, only what has previously come to light of its own accord and has shown itself to him in the light it brought with it. – Martin Heidegger [3]

Are the new online AI art apps, like Craiyon, “the Birth of a New Artistic Medium”, [4] “a Toy” — the fine art equivalent of junk food — “…or a Weapon”? [5] Parsing the hype from substance in the debate requires dimensional analysis, because AI t2i apps are one minor facet in a major technological advance happening across all sectors reliant on speedy decision-making for real-time, real-world adaptation to complex-system problems. Starting with an examination of the application acquaints us with its instrumental characteristics. Familiarizing ourselves with its quality/-ies can shed light on its projected value and shortcomings, as a popular commercial tech tool. A cursory introduction to Craiyon, helps us evaluate more essential questions about AI, what and who it is for, or against, and how.

∞

“Reality is challenged on the grounds of its objectivity, situated as an idea and thus turned into an object of calculation and operation.” – Wolfgang Schirmacher, from “Heidegger’s radical critique of technology as an outline of social acts.” [6]

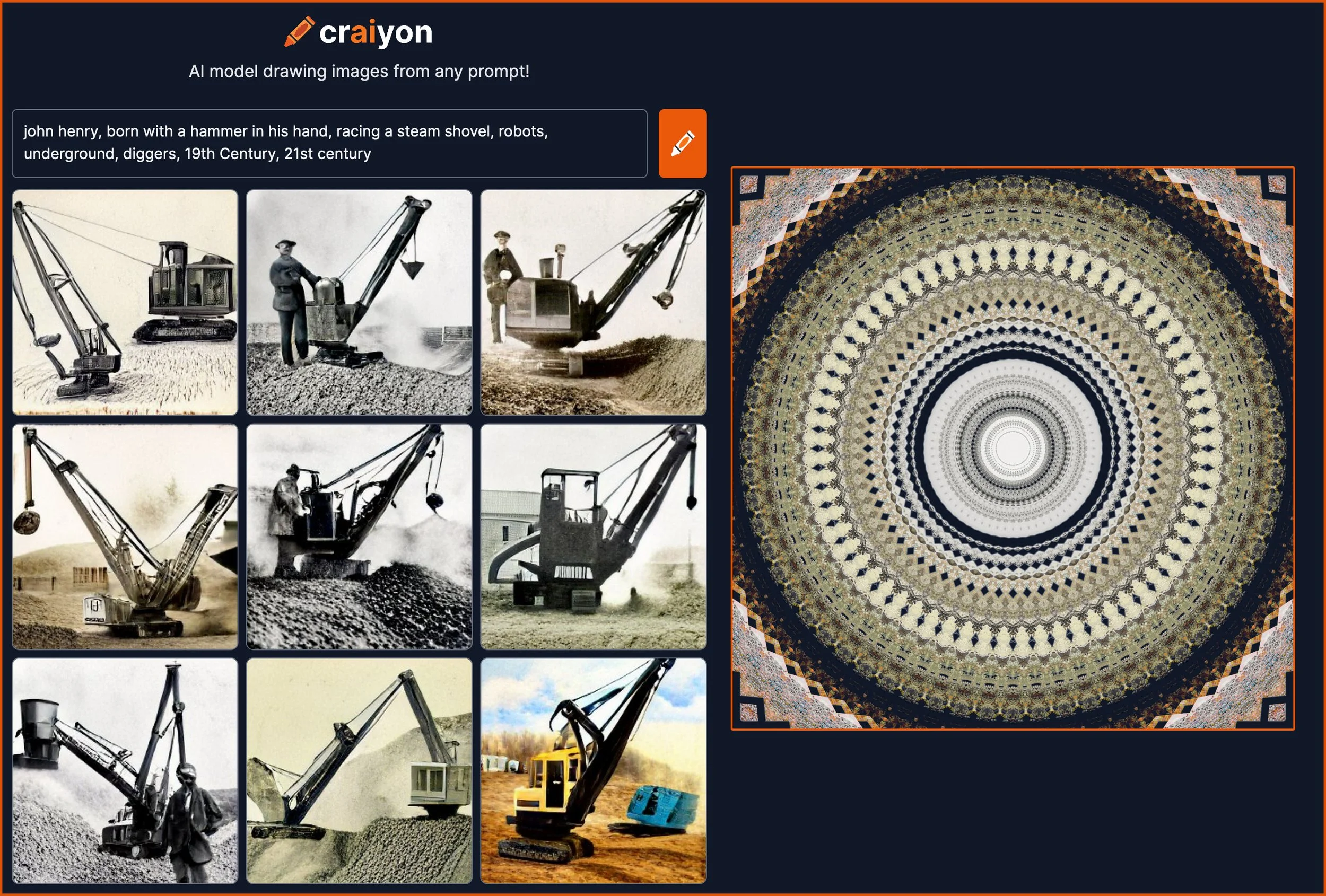

Schirmacher’s observation applies to Craiyon, and the latest AI t2i generators. Landing on the Craiyon web page (www.craiyon.com), we find a well-designed, if innocuous, interface, described in more detail below. The user is prompted to feed text of her choosing into Craiyon’s form. For our trial, we insert sequenced words and phrases, punctuated or not, into the “synthetic media” engine: for example, “Heidegger” and “van Gogh’s shoes”, [7] “Wolfgang Schirmacher Philosopher,” and “Homo Generator”, “mushroom cloud” “the Creation of Adam” by “Michelangelo”, “robot” and “motherboard”, “Damien Hirst”, “photo-realism”, “post-contemporary”, and so on. In less than two minutes’ time, the machine will serve up a half-dozen graphic mash-ups, baked from a gigantic trove of Net-scraped images, algorithmically derived from the word salad the user types into the Craiyon form.

Scrutinizing the Craiyon output, what is one looking at, or -for? In the app’s Mechanical Gaze, are we seeing how the Machine sees us? Is Craiyon capable of interpretation, or redefining the meaning of that word? Doe the app mesh us to ourselves and everything in the world we can think of and contextualize? Is the Craiyon output a visual form of complex collateralized derivative, an optical relative of those fin-sector WMDs that predicated the Crash and Great Recession of 2007-8? There are structural similarities between the phenomena, especially if we see a flood of AI art “collapsing” the social exchanges for networked images, as seems to be happening currently.

The admonitions of Heidegger on Enframing creep into the AI t2i call-and-response mechanism. What exactly is being exchanged here? From the first interplay of user and AI art apps, we are drawn into (seduced by?) a relation that evokes Heidegger’s Question Concerning Technology, and is extensive of his thoughts on the Thing and in “The Origin of the Work of Art”:

…Enframing does not simply endanger man in his relationship to himself and to everything that is. As a destining, it banishes man into that kind of revealing which is an ordering. Where this ordering holds sway, it drives out every other possibility of revealing. Above all, Enframing conceals that revealing which, the sense of poiesis, lets what presences come forth into appearance. As compared with that other revealing, the setting upon that challenges forth thrusts man into a relation to that which is, that is at once antithetical and rigorously ordered. Where Enframing holds sway, regulating and securing of the standing-reserve mark all revealing. They no longer even let their own fundamental characteristic appear, namely, this revealing as such. [8]

From the outset the AI t2i data base is identifiable as “the standing-reserve”. But this linkage is complicated and convoluted, due to the opaque means by which Craiyon’s image pool is acquired and enclosed. We are supposed to be thrilled by the Machine’s capacity to match words (ideas/εἶδος) to machine-selected graphics as an act of creation. We are not encouraged by the app designers on a critical level to notice that the rendering happens without our meaningful involvement. To put it in another frame of reference, the commercial, this creative-relational dynamic is converted to a “selling point” rooted in near-instant and -labor-free sensual gratification. A pixel is not an artist’s brushstroke, but for millions of users it is a sufficient estimate. One cannot help but think of Baudrillard’s Simulation and Simulacra here: “But mostly because our culture dreams, behind this defunct power that it tries to annex, of an order that would have had nothing to do with it, and it dreams of it because it exterminated it by exhuming it as its own past.” [9]

Craiyon has been pushed already as a time- and labor-saving tool for commercial artists. In this human-machine “collaboration” all the most (traditionally) valuable craft-elements of artistic creation are withdrawn from us and conceded to the device. It is hard not to identify this procedure as “setting upon” and a challenging forth of that most human of pursuits, one aligned emphatically with truth. Heidegger, continues, expanding on the danger technology represents.

Thus the challenging Enframing not only conceals a former way of revealing, bringing-forth, but it conceals revealing itself and with it That wherein unconcealment, i.e., truth, comes to pass. [10]

Heidegger is specific about the danger from technology, and his essay brilliantly outlines the problem. He also secures reason for hope, for which technology may prove the catalyst. Craiyon is an embodiment of prescient technological Enframing as Heidegger projected. His was the essential interrogation. Today we must summon discursive potency to a more comprehensive awareness of the extent to which technology and Enframing define our world experience. The enforcement of technological inevitability is generally met with complicity, escapism or nihilism, but we may find reminders of other ways of being and becoming outside the Tool and instrumentalization, beyond Enframing. If the prospect of a consequential tech Reformation is made to appear, and actually is, daunting to most of us, we do have available examples of other ways of being and becoming extant in this moment, which embrace poiesis, and man’s “free essence,” “the innermost indestructible belongingness of man within granting.” [11] Schirmacher’s thinking affirms this positivity toward the subjectivation of the artificial. “Technology is not to be used, but lived,” he states. [12]

Prompt from Benjamin’s “The Arcades Project”

THIS IS NOT A FACE, A HAND, A FOOT, OR THE FOLD OF CLOTH.

I think that the problems of A.I. are not its ability to do things well but its ability to do things badly, and our reliance on it nevertheless. So the problem isn’t that A.I. is going to displace all of our truck drivers. The fact that we’re using A.I. decision-making at scale to do things like lending, and deciding who is picked for child-protective services, and deciding where police patrols go, and deciding whether or not to use a drone strike to kill someone, because we think they’re a probable terrorist based on a machine-learning algorithm—the fact that A.I. algorithms don’t work doesn’t make that not dangerous. In fact, it arguably makes it more dangerous. The reason we stick A.I. in there is not just to lower our wage bill so that, rather than having child-protective-services workers go out and check on all the children who are thought to be in danger, you lay them all off and replace them with an algorithm. That’s part of the impetus. The other impetus is to do it faster—to do it so fast that there isn’t time to have a human in the loop. With no humans in the loop, then you have these systems that are often perceived to be neutral and empirical. - Cory Doctorow [13]

“John Singer Sargent once described a portrait as ‘a likeness in which there is something wrong about the mouth.’” [14] We discover the novelty AI art t2i generators take Sargent’s cheeky provocation at (inter-)face value. The immediate results are often horrible and grotesque. The illustration above is an example of Craiyon’s gruesome treatment of Walter Benjamin’s visage. As an artistic effort at representation, call it what it is: an abomination, a nightmare, a graphic failure, a heinous distortion, a visual affliction. Yet, AI does not regret its aesthetic inadequacy, does not possess or show remorse or embarrassment, as a first-year art student might do. In short, the Machine artist is unconscionable, and immune to critique. Its “training” is not pedagogical. It evidences the semantic issue of engineering heinous outcomes with a short-term returns rationale – by choice, on purpose! At least, that is what the manufacturers would have us believe. From the Craiyon site FAQ, under “Why are faces so weird?”: “It’s a limitation of our current image encoder. We are working on developing a better solution.” [15]

“Very Blue Robot” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

A BETA “bug” sortable later is viewed in Silicon Valley as justifiable on the basis of expedient competitiveness. What’s worse, Craiyon fails most acutely at those pictorial elements wherein humanity finds its most desirable self: the eyes, fingers and hands, feet, faces and so on; i.e., our most expressive extremities. Not only of the body, but of that by which our bodies are concealed by us, and through which we reveal ourselves – our clothing. Should we take this particular AI art t2i failure as signifying something else in our relation to it and its Machine vision? What responsibility must its “teacher(s)” or “training” bear for Craiyon’s performance? The Old Models of art instruction emphasize that layer of accountability. Craiyon transfers the onus to us, in the text provision, and inferred terms of engagement, echoed by industrial user-commentators. Are we to understand that the user is complicit in this mech-educational complex, via the prompt, a relation that blurs accountability for the poor quality of the gadget, in its technical execution. Cory Doctorow’s caution regarding AI applications is relevant to the art question, too, if we adhere to an art historical, art technique or craft tradition. Also at stake, obliquely, is the oral art history and traditional means of art-systematic transmission, over generations. Training an image-generator by text-prompt is obviously not equivalent to academic or studio art education, wherein a student can be shown in-studio technique by a competent or expert instructor. How, in the reconfiguration of protocols and programming, or why, are AI art advocates so keen on highlighting the technology’s potentially disrupting power in the art field? This disparity between educational speech and action programmatically is a key clue. We have seen technologists and their advocates be overtly intentional in their objectives for programming humanity. They over time hope to supplant the inter-personal relation with proprietary machines and processes. The campaign is one vital piece of a long-range strategy for the acquisition of power and wealth in future civilization.

Beyond the mechanical deficiencies, these much-hyped apps hide the rise of this global power-shifting, cross-sector technology (AI) behind the smiley face of endlessly clickable online amusement. On an existential level, at stake is the role of language, not just in art, but throughout the medium of human exchange. Walter Benjamin opens his essay “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man,” which significantly precedes his seminal “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” with the statement “Every expression of human mental life can be understood as a kind of language, and this understanding, in the manner of a true method, everywhere raises new questions.” [16] AI a2i creates a crisis in the connection between art, language, but more importantly the process of, as Heidegger situates it, the vital process of revealing the essential man-language-art combined serves to construct. AI does act to remove humanity from the generative nature of creation, endangering its functional discernment, and making inevitable mechanistic mistakes with horrible consequences. Viewed from this angle, AI art’s failures are but the canary in the coal mine.

With Benjamin’s contention about language and human expression in mind, it should come as no surprise that OpenAI followed its launch of DALL-E and DALL-E 2 with an upgrade to its interactive dialogue machine ChatGPT (openai.com/blog/chatgpt/), as the 2022 wave of interest in popular AI crests. The Turing Test is now a relic of the Real. InstructGPT is another OpenAI model in production. The three OpenAI tools in tandem expose the breadth of the project, in the context of language-oriented or -rooted expression. Marx’s parenthetical in his Fragment on Machines resonates with this lateral development approach: “What holds for machinery holds likewise for the combination of human activities and the development of human intercourse.” [17] The text enclosing this remark only adds to its relevance in the early 21st Century. The industrial expansion is defined by convolution in artificiality, and as such offsets natural and humane revolutionary drives.

Here it is necessary to address directly the labor question and AI, if only briefly. As Vice writer Chloe Xiang reveals in her article “AI Isn’t Artificial or Intelligent:”

The biggest tech companies in the world imagine a near future where AI will replace a lot of human labor, unleashing new efficiency and productivity. But this vision ignores the fact that much of what we think of as “AI” is actually powered by tedious, low-paid human labor. [18]

The AI industry is replicating the extraction and exploitations schemes of the past. Amazon Mechanical Turk, and companies like content moderator companies Samasource, Scale AI, and Mighty AI and “crowd worker marketplace” Clickworker, collaborate to create and maintain a huge precarious labor force without which AI as we experience it would be impossible. The work is largely outsourced to the Global South/Third World. Its laborers are poorly compensated, have little upward mobility and few of the workplace recourse or benefits we in the Global North/1st World do. Worse, some, such as the content mods, are repetitiously exposed to horrifying images of the sort we expect protection from (e.g., images of rape, murder, torture, child abuse and so on). This is the gritty reality of AI industrialization, which is wholly out of sync with the glossy tech projection promoted in AI push marketing and advocate hucksterism. Xiang continues:

Experts say that outsourcing these workers is advantageous for big tech companies, not only saving them money, but also making it easier for big tech companies to avoid strict judicial review. It also creates distance between the workers and the company itself, allowing it to uphold the magical and sophisticated marketing of its AI tools. [19]

We are learning that deeper dive into the dimensional apps for AI art unveils troublesome hidden realities, on the matter of our collective and individual vulnerabilities to dimensional absorption, or Enframing: databases that harvest every image posted to the Net, absent the attribution, consent or compensation of the maker; programmatic re-sampling of those images to “create” monetizable “originals”; attention machines that double as systematic advertising revenue engines; metadata Hoovers, which can catalog the visualization desires of millions of users in the Cloud, absent any industrial or academic oversight, governance or regulation. Culturally, AI is symptomatic of systemic malaise: the shift from human to machine expression is a blurring of originality, which affects the apparatus for determining authenticity, accountability, while subverting the relevance of tradition or craft in evolutionary production.

The technologist has already in large measure virtualized the handiwork of humanity, where episteme and techne exist in beneficent exchange. Now, are we witnessing the tech-enabled co-optation of the imagination, meaning the conjunction of thought and vision — achieved by a meta-Moron*, the networked computer? Are we wondering, who might benefit from this, and also, who or what is harmed? What are they** really after? Art and Philosophy might offer us some clues, if not answers, originating in a poiesthetic neo-criteria, which inducts the applied philosophy of Marx, Benjamin and also future-oriented literary technologists, whose visions apply presently, i.e., Cyberpunk, but also Orwell and Huxley, and others. We must acknowledge that the AI phenomenon is simultaneously symptomatic, systematic and symbolic. It has further evolved into a symbiotic facility, fully expressive or expressionistic of the technological danger, as precisely identified by Heidegger.

*“We are beginning to realize that the computer makes no decisions; it only carries out orders. It’s a total moron, and therein lies its strength. It forces us to think, to set the criteria. The stupider the tool, the brighter the master has to be—and this is the dumbest tool we have ever had. All it can do is say either zero or one, but it can do that awfully fast. It doesn’t get tired and it doesn’t charge overtime. It extends our capacity more than any tool we have had for a long time, because of all the really unskilled jobs it can do. By taking over these jobs, it allows us—in fact, it compels us—to think through what we are doing.” — Peter Drucker, “The Manager and the Moron” (1967) [20]

** Doctorow identifies “them” variously, but also specifically in the cited interview, as “completely ordinary mediocre monopolists, doing what monopolists have done since the days of the Dutch East India Company, with the same sociopathy, the same cheating, the same ruthlessness.”

PART TWO

“Not Martin, Vincent or Shoes” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

PEELING THE ONION

"What appears familiar, self-evident, ordinary, everyday, natural, certain, and suggested is also the most uncanny: the murderous grimace in the mirror of our acts." Wolfgang Schirmacher, “Living in the Event of Technology” [21]

Three current developments highlight the important complex role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on the world stage, from macro- to micro-levels. The first encapsulates what we might call the proto-cultural aspect of AI. AI-da, the performative artist-robot testified before committee at the UK’s House of Lords. “She” answered pre-prepared questions from members, one of whom, namely Baroness Featherstone, declared herself “partly terrified” by the encounter. According to Artnet, Featherstone had asked AI-da about the future role of technology in art, to which the robot replied:

“The role of technology in creating art will continue to grow as artists find new ways to use technology to express themselves, and reflect and explore the relationship between technology, society, and culture,” Ai-Da said.

“Technology has already had a huge impact on the way we create and consume art, for example the camera and the advent of photography and film. It is likely that this trend will continue with new technologies,” she added.

“There is no clear answer as to the impact on the wider field, as technology can be both a threat and an opportunity for artists.” [22]

The second development reveals the geo-political aspect of AI. The USA Biden administration announced new export restrictions on advanced chip technology “needed to train or run the most powerful AI algorithms to China.” The new rules “kneecap the high-performance computing efforts of China,” according to one expert. [23]

What is AI? Generally speaking, it is a blanket term for advancements in the field of computation, which extend human capacity to solve massive problems. AI “refers to systems or machines that mimic human intelligence to perform tasks and can iteratively improve themselves based on the information they collect,” according to tech giant Oracle. [24] Parsing this banal definition, we can begin to picture the main components of AI: a machine or system; the mimicry of human intelligence; the functional capacity of self-improvement derived from collected data. When confronted with the embodiment of the technology (AI), why would a powerful person feel “terrified?” When the West cuts off the supply of parts necessary for AI production and advancement, why and how would this technological blockade adversely impact China and its ambitions? According to Wired magazine, “Big Tech companies in China—as in the US—have made large AI models increasingly central to applications including web search, product recommendation, translating and parsing language, image and video recognition, and autonomous driving. The same AI advances are expected to transform military technology in the years to come, and shape how the US and China butt heads over issues like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Taiwan’s claims to independence.” [25]

“Never Touching” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

Obviously, the areas impacted by the embargo are essential to the Chinese quest for hegemonic power, by displacing the USA as sole hegemon after a period of global de-centralization. Naturally, the US and its key allies fear and resist this. Returning to testimony of AI-da at Parliament, do these two instances of AI belong in the same conversation? It is this text’s contention that they do, along with a third, and that together they point to a juncture of philosophical and aesthetic interests in the questioning of technology itself, as well as what we might call “Self-technology.”

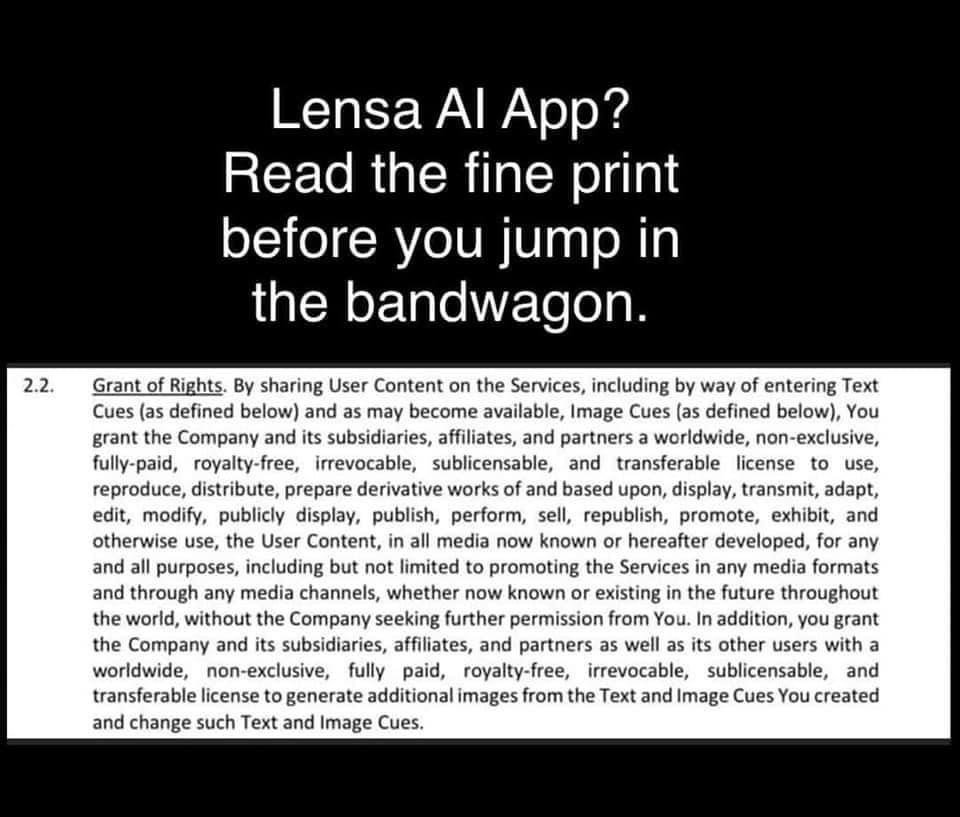

The third correlating development must also be addressed. It arrives in late 2022 with the viral popularization of Prism Labs’ LENSA product Magic Avatar, a technology which explicitly exploits post-contemporary Selfie-ness. The user-friendly thrust of AI-driven apps continues with the next Big Thing in AI t2i technology. In an article (one of many) titled “A Viral A.I. Generator, Which Allows Users to Conjure Up Their Own Self-Portraits, Has Sparked New Concerns About Creator Rights,” Artnet’s Richard Widdington outlines the phenomenon concisely. LENSA uses a variant commercial approach, pay-to-play, but trades on the desire of consumers to be virtually reproduced in an enhancing, graphic manner of depiction. [26] Users purchase machine-generated stylizations derived in part from a set of “Selfies” or clipped pictures of themselves, submitted to the LENSA engine. LENSA, after twenty minutes’ processing time, outputs a set of digitally rendered versions of the customer’s face and some, often misshapen, body parts. These sharable representations have inundated social media feeds. Widdington’s introductory article examines the details of the apparatus in a balanced presentation of content and context, covering ethical and technical questions responsibly, journalistically speaking. Many of the problems apparent in the Craiyon model apply to LENSA, along with some new ones. Perhaps a more interesting (subjective) observation is found in a follow-up article by Artnet contributer Sarah Coscone, who submits her own images to LENSA. She writes, after some reflection:

In my first glance at my Lensa results, I really did feel like I was staring at a (highly stylized) reflection with some of the images…But now, the more I look through them, my sense of self is becoming less certain. Is that actually my mouth? Do my eyes really look like that? I feel as though I’m starting to doubt my ability to recognize my own face—a reminder that A.I. art remains a strange new frontier, even as it grows more omnipresent. [27]

Another anecdotal user response, this one by Salon writer Kelly McClure focuses on the sources of LENSA’s attraction to self-image collectors, and what compels them to toss aside tech-prudence and caution to play with the latest AI a2i toy. McClure reveals her motivation in a net-colloquy:

Random Larry from the internet might think I have a pig nose, but what does artificial intelligence think? If I can't ask a friend or a stranger if I'm pretty and feel comfortable doing so, let's have a computer show me and just be done with it. Beauty as science. As math. Is about as blunt of a reply as one could hope for. [28]

What is the user trading for having an AI machine serve as “mirror, mirror” for millions of digital users hungry for a quick, post-able, virtual makeover? Below is a reproduction of the LENSA contractual terms, circulating on social media.

ART, BY THING?

Critic Ben Davis devotes a chapter to AI in his excellent new book Art in the After-Culture. Entitled “AI Aesthetics and Capitalism, the chapter provides a solid introduction to the phenomenon of AI and its induction into the art world. In one of his concluding paragraphs Davis writes:

It is neither wishful thinking nor metaphysical delusion that there are aspects of artistic experience that are not amenable to simulation of the kind now insinuating itself into the cracks of our creative life, or that we are at risk of a surrender of those aspects if they are neglected. You can respect the wonders of the technology and still believe that. [29]

What is Ben getting at? I think Davis suspects, as many do, that humanity might ultimately concede its imagination and autonomy to the Machine. This gloomy outlook is hardly novel. It emerged with the onset of the Industrial Age and has burgeoned throughout the Digital Era. As stipulated above, we have inarguably already conceded much in the vast expanse or sphere of laborious human craftsmanship to machines. Supplanting the creative is the next industrial and technological objective. Many of us rightly worry that megalomaniac techno-industrialists’ wish fulfillment is of the “winner takes all” variety, which is part of the Silicon Valley ethos and mythos. [30] Why should we be shocked when they mobilize to absorb the immaterial aspect of creation, along with its material apportionment? Tech barons thrive as the exclusive and immediate beneficiaries of industrial insatiability! The codifying of “intellectual property” was simply the first step in this direction. In great measure this development has been the source of tech-industrialist Bill Gates’ fortune, and many others who have followed in his footsteps.

However, before the digitalized masses surrender the “aspects of artistic experience” (to which Davis refers) to a mech-mimic, operating as a proxy for oligarchic technologists, we should inspect not only the mechanical vision of humanity as it is revealed to us in these apps’ BETA stage visualization engines, but also as it is expressed (or not) in the formalities of the structural crafts on which they feed. Through the tactic of submitting both virtual and actual or analog media to thorough and subjective seeing, we may find true perspective, discovering valuable clues, like, what the “happy face” [31] of AI hides, its deeper mysteries. What wizardry – or malpractice and -feasance - is hidden behind the technology’s silicon curtains? Following Heidegger’s lead:

“All Days End with ‘Why’ in the West” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

We wish to hit upon the immediate and complete reality of the artwork, for only then will we discover the real art within it. So what we must do, first of all, is to bring the thingliness of the work into view. For this we need to know, with sufficient clarity, what a thing is. Only then will we be able to say whether or not an artwork is a thing – albeit a thing to which something else adheres. Only then will we be able to decide whether the work is something fundamentally different and not a thing at all. [32]

“Creating Nothingness” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

The AI at2i generator is an online tool. The user enters and submits individual word or series of word prompts in a form-field. A button click begins the processing of the text into a set of six images, congealed from a massive data base of image files. The process requires a short wait of a couple minutes or less, during which a “waiting” GIF icon pulses and the Craiyon icon on the submit button wobbles. The latest site update introduces a timer. During the wait, one can (subliminally or consciously) consume the advertisements flanking the generator and above it, as they change regularly, courtesy Google, AdChoices, the Digital Advertising Alliance, et al. The web page is dark blue with complementary orange accents, and white text. Once the image appears, the user can click for a screenshot or to join a forum. Scrolling down, the user finds a FAQ, reversed orange and blue, then a black/grey on white area containing contact info and an invitation to subscribe to a Craiyon community.*

* The blue/orange Craiyon site design evokes the original Blogger site Net-aesthetic.

Craiyon poses as a “free” app. Is it? The user pays in attention, which in the current mode, translates into advertising income for the publisher and partners. Also, the text submitted to the tool is valuable data for multiple proprietary purposes, commercial, technical and more - and can be monetized by the owners, sold and repackaged or bundled. In this schema, the user participates as an uncompensated BETA tester. Craiyon is structurally similar to a one-arm bandit gambling machine, except the former offers no potential payoff besides the graphic, which disappears if one leaves or refreshes the Craiyon page, or if one downloads the image or sends it to social media.

Post-Snowden, is one paranoid to assume that all user actions and outputs in this game are traceable data points? In the post-contemporary, it depends on who wants to know. In the Total Information Awareness age, is it outlandish to suspect that hidden, invisible “entities” – i.e., private or public institutions and actors - on the “back end” of the widget, beyond the metadata, would very much like to know what every user who plays Craiyon or any of the AI t2i generators is thinking about while playing, or at any given time? Despite assurances to the contrary from the app makers, we really have no way of being sure about their integrity on issues of online privacy and data extraction and exploitation. Past experience suggests that nothing on the web is unhackable. Access to private thought is immensely valuable for business ends, but other ends, as well. Given this axiom: Craiyon is an opaque or Black Box tool that channels “wondering” into an extractive machine designed to facilitate harvesting that wonderment and analyzing it; Is it something worse? We ought to proceed under the assumption that the database containing all that accumulated wonder generated by the gadget can be repurposed to other ends. Whether it is or not is beyond the end user’s access and control, for now.

So far, what are we looking at? Technically, Craiyon at this stage in this iteration is not unlike innumerable other online apps, most of which do not prioritize any aesthetic angle. Craiyon, at one level of usage, can be “played” like a mindless entertainment and typical among “toys” or “games” that foster repetitive action, to the extremes of addiction, while extracting user metadata and attention, with site-based preferential ad programming, e.g., Bejeweled. [33] Craiyon is also apparently just a BETA test in an AI t2i schematic, replete with promises of a better-engineered product currently in program development, one among many. Who are some of the industrial leaders behind the AI wave of popular production, its big boosters, energizing the domain? The usual suspects: Microsoft, Google, Apple, etc. The intermediaries are engineers, entrepreneurs, labs, etc. These enormously powerful corporations are in turn intricately interwoven into the mesh that combines the financial sector, international trade, and the institutions established to govern the exchanges, not to mention the mechanisms by which this conglomeration is monitored, enforced and mediated.

“Not-creation + Not-witnesses” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

THE CLAW OF CREATION

The images produced in the author’s experiment with Craiyon illustrate some of the obvious weaknesses of the app. The representation of the human figure is a challenge that Craiyon performs poorly. Hands and faces are rudely, sometimes horridly deformed by it. We notice strange discontinuities and asymmetries that disrupt the viewer’s willingness to construe realism within the images Craiyon generates. The program fails in the details. It finds clothing particularly problematic. The coloration is off. One could continue, but an exhaustive list of idiosyncrasies and outright flaws would be prohibitively long.

The text-to-image feature commonly yields disappointing results. It is not easy to explain the logic of the interpretive choices made by the AI image generator. The optimization of prompts is foisted on the user, who has no direct access to Craiyon’s decision tree. For this artist, the overall judgment on the app is that it is a buzz-creating device with diminishing creative value. For digital art image sampling, Craiyon produces some content that has potential as a point of origin, but for practices like mine, this is true of practically any image file. The “inspiration” quotient Craiyon-based images contain does not compare well to a visit to a quality museum or stroll in any notable city or attractive locale. Glossy magazines and Youtube outshine Craiyon in this respect.

We have been assured that more powerful AI text-to-image generators are in the pipeline. There is some evidence to support this contention. Any veteran of the digital medium knows to maintain skepticism at such assurances. Maybe later generations of this tool will be much improved. For the amount of push and investment behind the project, one would hope so. At present, the technology is an underperforming novelty item. In a couple of years, AI t2a generators have advanced in quality from something comparable to a talented 2nd grader’s work to that of a 6th grader, who can repetitively do rote or stylized faces but has a problem with hands.

“Post-Contemporary Non-Event” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

“A HUMAN BEING IS NOT A THING.” [34]

Heidegger’s statement is invaluable to any critique of AI t2i generators. In the post-contemporary period, there is a profound escalation in the ancient tension between the sublime/seeking for perfection/utopian (heavenly) and the abject/the misshapen or mutant/dystopian (hellish). It has occurred to me that the most troubling development materializing in the Twenty-first Century is Man's projection of the qualities of the Divine upon a Machine (and its works), which are absolutely not capable of meeting those displaced human expectations. The sentiment is never reciprocated. Meanwhile, reality, as such, is falling to pieces.

Not Seen Before or Since” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

Maybe there is no harmlessness in human technology, but the type of harm bound to technology is provisional. If we include art within the sphere of the technological, art so contained might or might not provision harm. Upon closer scrutiny, is this really true, and how could one tell, if it were or not? A pursuant question is, “Harm to what or -to whom?” We also have mitigating instances of tech-embracing artists whose pursuits are benevolent, oriented to healing and correcting historical wrongs in the present, for the future. An artist who epitomizes the practical embrace of technology by post-contemporary artists is Amelia Winger-Bearskin, whose work veers from canonical concerns into territory that claims a traditional space grounded in an indigenous worldview, more in affinity with those people and collectives previously marginalized in historical hierarchies. Post-colonial perspectives are being put forth through the latest expressive technologies. Adherents to establishment definitions of art may find such developments harmful on the basis of aesthetic continuity, but is this new art world order an extension or a threat? A similar interrogation of technology is warranted. In an interview with Pier Carlo Talenti, Winger says:

I think there are a lot of assumptions around AI being neutral, being true, being more true than opinions, being more distanced from the petty arguments of mortals or whatnot, when in fact it’s totally biased, it has an immense amount of problems and it’s leaving out enormous amounts of very vital data in our planet in a lot of these systems. In many ways it’s consolidating power and consolidating avenues of harm for certain communities and for things like our planet. [35]

“This Is Not a Cartoon” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

Fortunately, there are still art and philosophic practitioners concentrating their work on the thorny aesthetic and theoretical implications of technology “insinuating itself into the cracks of our creative life,” as framed by Ben Davis above. Felipe Daniel Montero writes, “In ‘The Question Concerning Technology’, the essence of technology as enframing (Gestell) is characterized as the hegemonic mode of unconcealing in our times. In this way, art and technology are revealed as diametrically opposed modes of unconcealment or truth.” [36]

Heidegger’s invention (convention?) Enframing has proven to be a profound and relevant lens through which to view the virtualization of humanity into the post-contemporary period. Gestell is also a synesthetic device by which art – and we -- can be “saved”, a path to poiesis, a move or technic that provides a necessary distance between art and technology, artists and technologists. This outcome is obtainable, when Enframing is contra-presented within the art, suspended and mitigated or overcome. There are many examples of this maneuver in post-contemporary art. In fact, it is one of its defining characteristics and features, and so leads to some surprising transmedia examples and associations, as artists of the period wrestle with the implications to their art, theory and applied technologies. [37][38]

Heidegger’s saving vision offers us an “out”, the 21st Century version of Deus ex Machina, a get-out-free gambit to play in this dangerous technological game. The confusion or conflation of art and technology more than ever is a polysemic matter, because of the common usage of tools and applications for divergent reasons and outcomes, all rooted in common language of numbers and naming. The value of Schirmacher’s insight is clarified with the proliferation of apps like Craiyon, which posit a specific but only partial meaning for the idea of “generation,” resonant with the others, but falsely equivalent to them. One’s maintaining total awareness of much more advanced AI technologies than Craiyon being developed and used in all sectors of society (for “good” and/or “bad” ends) is an impossible task. Developing life techniques in the event of technology is always possible.

“The Not-thinker” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

A FEW THOUGHTS ON CREATIVELY RESISTING TECHNOLOGICAL INEVITABILITY

On the one hand: “Nothing is to be done.” On the other: “We always find something…to let us think we exist?” [39] Beckett and Godot remain relevant well into the 21st Century, and on the question of AI industrial apps, even the “fun” or “inspiring” diverting ones. In critiquing “AI” we must first recognize the difference between distinguishing and depiction, as signs of sentience. Comparative interpretation is not displayed in Craiyon. Instead, the user is provisioned variation with a hint of infinite possibility, which is not available to the human at the keyboard, except as a concept or dream. Routinely, the AI-generated image represents nightmarish disfiguration in the flattening context of Play. Repetitive use will not go well for us, or at least those of us dedicated to Real art, and all it requires of the artist, viewer and society. We will lose our “chops”, then our conversations, and finally our memory.

The next recognition we must foster is the machine’s moronic compression of time as a factor of imagination. A dead or living philosopher, or another sort of person, for instance, will be reduced to a single chronologically determined plane, or rather, a set of pixels - not a lineage of thought connected to life lived and ended in context, on a continuum. The AI art output does not venerate human time, conditions or circumstances, adhering only to the definitions of time that operate the computer, or related external or network devices. Internal machine time is simply operational and metadatic (excepting the reality of obsolescence, which is uncomputed in a robotic mind, except in sci-fi movies like Blade Runner).

A third apropos recognition involves the terms of human-machine collaboration, which in this case, is complicated, but must be refined and defined more rigorously, moving forward. There is an ethical component, but it is unilateral, and its concerns are not reciprocated by both participants. Industrial technologists forcefully and cleverly resist all and any constraint. We concede the spaces for our imagination to tyranny, if they should prevail in their systematic games.

Our innate human drive combining preservation and observation extends to truth, meaning, values and other fundamental building blocks for theoretically informed art, and in turn, social organization, itself. The user should therefore be advised that the deep risk of play here is the abandonment of what makes making valuable to a thinking individual, and, collectively, to a society that is based on more than its technological advances in the service of dimensional, systematic power.

Lastly, there are the matters of craft and labor in art (and theory). The technologist unsurprisingly is utterly dismissive of techne (and episteme) in the tech-centric discourses enveloping post-contemporary artistic innovation. The valorizing of virtual “democratization”, as framed by the tech elite, over time has proven to have little to do with either people or democracy. Aesthetic craftsmanship, or artistic labor, cannot reasonably be deemed replaceable by typing short texts and clicking. To suggest otherwise is to promote techno-sophistry, and in the endgame, a kind of tech-enabled neo-feudalism for our imagination, which encompasses our dreams and self-sense. The image is not the only thing, virtual or otherwise.

“Art Like This Was Never Work” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon

FOOTNOTES

[1] Liam Gillick and J.J. Charlesworth, “Is This the End of Contemporary Art As We Know It?”, Art Review, September 29, 2020, https://artreview.com/is-this-the-end-of-contemporary-art-as-we-know-it/

[2] Christof Migone, “Neverything”, Mag Magazine, September 2022, https://mapmagazine.co.uk/neverything

[3] Martin Heidegger, “The Thing” in Poetry, Language, Thought, translated and edited by Albert Hofstadter (New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2013), 70.

[4] Stephen March, “We’re Witnessing the Birth of a New Artistic Medium”, The Atlantic, September 27, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/09/ai-art-generators-future/671568/.

[5] Matteo Wong, “Is AI Art a ‘Toy’ or a ‘Weapon’?”, The Atlantic, September 23, 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/09/dall-e-ai-art-image-generators/671550/.

[6] Wolfgang Schirmacher and Torgeir Fjeld, “Heidegger’s radical critique of technology as an outline of social acts”, Inscriptions, July 1, 2018, https://www.tankebanen.no/inscriptions/index.php/inscriptions/article/view/17/21.

[7]Suzanne Bloom and Ed Hill, “Borrowed Shoes”, Artforum, April 1988, Preface, https://www.artforum.com/print/198804/borrowed-shoes-34739.

[8] Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art” in Poetry, Language, Thought, translated and edited by Albert Hofstadter (New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2013), 27.

[9] Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, 10. https://0ducks.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/simulacra-and-simulation-by-jean-baudrillard.pdf

[10] Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 27.

[11] Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 32.

[12] “Eco-Sophia: An Interview with Wolfgang Schirmacher,” interview by Alexander Kopytin, Ecopoiesis: Eco-Human Theory and Practice, December 21, 2020. https://en.ecopoiesis.ru/interviews/article_post/eco-sophia-an-interview-with-wolfgang-schirmacher

[13] “Cory Doctorow Wants You To Know What Computers Can and Can’t Do,” interview by Christopher Byrd, The New Yorker, December 4, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-new-yorker-interview/cory-doctorow-wants-you-to-know-what-computers-can-and-cant-do

[14] Laura Cumming, “Facing the truth about portraiture”, The Guardian, November 15, 2006, Preface, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/artblog/2006/nov/15/facingthetruthaboutportrai

[15] https://www.craiyon.com/#faq

[16] Walter Benjamin, “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man,” in Walter Benjamin Selected Writings Volume 1 1913-1926, edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press), 2. https://dokumen.tips/documents/benjamin-walter-language-as-such-and-language-of-manpdf.html?page=1

[17] Karl Marx, “The Fragment on Machines” from The Gundrisse. https://thenewobjectivity.com/pdf/marx.pdf

[18] Chloe Xiang, “AI Isn’t Artificial or Intelligent: How AI innovation is powered by underpaid workers in foreign countries,” Vice, December 6, 2022. https://www.vice.com/en/article/wxnaqz/ai-isnt-artificial-or-intelligent

[19] Xiang, “AI Isn’t Artificial or Intelligent: How AI innovation is powered by underpaid workers in foreign countries.”

[20] Peter Drucker, “The manager and the moron”, McKinsey Quarterly, December 1, 1967. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-manager-and-the-moron

[21] Wolfgang Schirmacher, “Living in the Event of Technology”, Inscriptions, Vol. 4 No. 1 (2021), 7. https://www.tankebanen.no/inscriptions/index.php/inscriptions/article/view/93

[22] Jo Lawson-Tancred, “Robot Artist Ai-Da Just Addressed U.K. Parliament About the Future of A.I. and ‘Terrified’ the House of Lords”, October 12, 2022, Artnet, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ai-da-robot-artist-parliament-2190611

[23] Will Knight, “US Chip Sanctions ‘Kneecap’ China’s Tech Industry”, October 12, 2022, Wired, https://www.wired.com/story/us-chip-sanctions-kneecap-chinas-tech-industry/

[24] What is AI? Learn about Artificial Intelligence”, Oracle, accessed October 18, 2022, https://www.obracle.com/artificial-intelligence/what-is-ai/

[25] Knight, “US Chip Sanctions ‘Kneecap’ China’s Tech Industry”.

[26] Richard Whiddington “A Viral A.I. Generator, Which Allows Users to Conjure Up Their Own Self-Portraits, Has Sparked New Concerns About Creator Rights,” Artnet, December 6, 2022. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/lensa-ai-magic-avatars-prism-labs-2224239

[27] Sarah Cascone, “I Uploaded Photos of Myself to the New Lensa A.I. Portrait Generator. The Results Were Stunnig, Strange…and Super Creepy,” Artnet, December 8, 2022. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/lensa-ai-avatar-results-2225393

[28] Kelly McClure, “A theory on why Lensa is turning us into AI thirst trappers with its ubiquitous portrait app,” Salon, December 9, 2022. https://www.salon.com/2022/12/09/lensa-is-turning-us-into-ai-thirst-trappers-with-its-ubiquitous-portrait-app/

[29] Ben Davis, Art in the After-Culture: Capitalist Crisis & Cultural Strategy (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022), 171.

[30] “Digital pioneer, Jaron Lanier, on the dangers of “free” online culture,” interview by Catherine Jewell, Wipo Magazine, April 2016. https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2016/02/article_0001.html.

[31] Tim Schneider, “DALL-E’s Astonishing Images Mask That Art Is Just Another Pawn in Silicon Valley’s Endgame (and Other Insights)”, Artnet, https://news.artnet.com/news-pro/gray-market-dalle-openai-art-history-2149487

[32] Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” Martin Heidegger: Off the Beaten Track, edited and translated by Julian Young and Kenneth Haynes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022). https://assets.cambridge.org/97805218/01140/excerpt/9780521801140_excerpt.pdf

[33] Andrew Lim, “The ten most addictive Flash games ever made,” Cnet, September 23, 2011. https://www.cnet.com/tech/gaming/the-ten-most-addictive-online-flash-games-ever-made/

[34] Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 4.

[35] Peter Drucker, “The manager and the moron”, McKinsey Quarterly, December 1, 1967. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-manager-and-the-moron

[36] Felipe Daniel Montero, “Art, Technology and Truth in Martin Heidegger’s Thought”, January 13, 2020, Blue Labyrinths. https://bluelabyrinths.com/2020/01/13/art-technology-and-truth-in-martin-heideggers-thought/

[37] Ernesto Priego and Peter Wilkins, “The Question Concerning Comics as Technology: Gestell and Grid”, The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship 8, 16. https://www.comicsgrid.com/article/id/3576/

[38] Joakim Vindenes, “The Mind as Medium”, Matrise. 2018. https://www.matrise.no/2018/06/the-mind-as-medium-virtual-reality-metaphysics/

[39] Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot: A tragicomedy in two acts/ by Samuel Beckett (London: Faber and Faber, 1956).

“Construct 8 [SYM]” by 01/PJM

REFERENCES

Contreras-Koterbay, Scott, Lukasz Mirocha, The New Aesthetic and Art: Constellations of the Postdigital. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2016.

Fjeld, Torgeir, Wolfgang Schirmacher. “‘Hope will die at last’: an interview with Wolfgang Schirmacher.” Inscriptions 1, no.1 (2018): 19.

Heidegger, Martin, The Question Concerning Technology. Translated by William Lovitt. Germany: Garland Publishing, 1977.

Heidegger, Martin, “The Origin of the Work of Art.” In Martin Heidegger: The Basic Writings, Translated by David Farrell Krell, 143-212. New York: Harper Collins, 2008.

Heidegger, Martin, Being and Time, Translated by Joan Stambaugh, revised by Dennis J. Schmidt. New York: SUNY Press, 2010.

Heidegger, Martin, What Is a Thing?, Translated by W.B. Barton Jr., and Vera Deutsch. Chicago: Henry Regner,1967.

Manovich, Lev, and Emanuele Arielli, Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media and Design; November 2021. http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/artificial-aesthetics-book.

Manovich, Lev. AI Aesthetics. Moscow: Strelka Press, 2019.

Schirmacher, Wolfgang, Ereignis Technik. Vienna: Passagen Verlag, 1990. Schirmacher, Wolfgang.

Schirmacher, Wolfgang, Torgeir Fjeld. “Heidegger’s radical critique of technology as an outline of social acts.” Inscriptions 1, no.1 (2018): 17.

Schirmacher, Wolfgang, Daniel Theisen. “Technoculture and life technique: on the practice of hyperperception.” Inscriptions 1, no.1 (2018): 20.

“Things Which Never Happen” by R. “Muddy” McRaiyon